Martin Scorsese has had a long, fruitful partnership with rock ’n’ roll as muse, subject, and accompaniment, and one thing at which he’s uniquely skilled is drawing out the playfully antagonistic relationship between performer and audience. Though 2005’s No Direction Home offered an exhaustive, four-hour look at a sliver of Bob Dylan’s career, it felt almost too civil–absent the combative spirit that has made Dylan such a prophetic and transmuting figure.

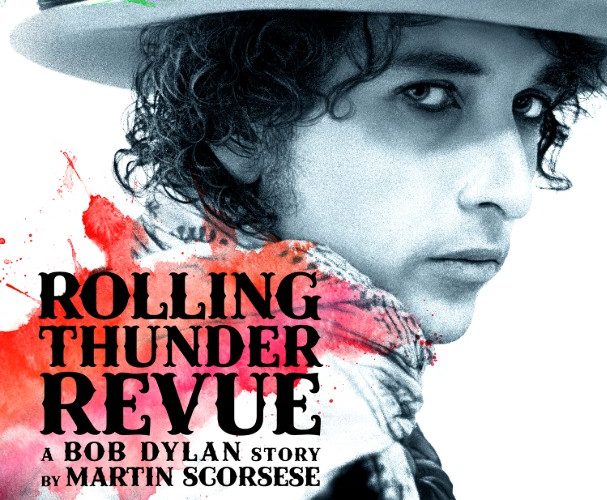

His latest attempt, Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story–a remastered chronicle of the nearly 60-date tour that took place from 1975-1976–is as indebted to Dylan in form as content. A grandiose lark at least ten years in the making, its opening as a stirring Americana collage belies its later, consciously scattered direction. This is a portrayal of Dylan at his most unadulterated and prickly–a desolate genius who’s still almost always full of it.

The atmosphere may feel like an elaborate gag, but the undercurrent of a destabilized 1975 roils and props up the entire spectacle–a consistent reminder that the world was in flux and people were looking for answers. But still after a contemporary Dylan hilariously invalidates the tour’s purpose as meaningless in the first five minutes. The lasting message, then, is less one of enduring significance than the need to document a time and place and bottle that feeling of immortality.

From a modern perspective, the tour is seminal–a hootenanny involving some of the greatest musical and artistic minds of the era, in some cases current elder statesman carrying the fire of that incorruptible time. Patti Smith doing beat poetry to a honky-tonk groove, for instance, isn’t important on its own, but it’s one of many fragments that here establish a singular texture for the moment and this group of people. This is the fabled Greenwich Village of the collective unconsciousness brought to anonymous recreation halls and small-town theaters, a spectacle that channels the hedonistic rock ’n’ roll lifestyle without glamorizing or reveling in anything other than the artifice. It’s sloppy and a little sleazy but also completely controlled.

In that respect, the first half of Rolling Thunder Revue less resembles Scorsese’s previous films or landmark concert films than last year’s Other Side of the Wind. There isn’t quite the dark-night-of-the-soul revelations and naked ego trips of Orson Welles’s jumbled cinematic psychosis, but Dylan’s disinterest in personal transparency and desire for solitude is plainly observed as he wanders through crowd after crowd of strangers. And the footage likewise cuts back and forth between Dylan and his tagalongs who hang on his every word even as the witticisms are often less nuggets of wisdom than alphabet soup. These digressions are essential to the mood, thick with weed and delusion and a potent melancholy.

The Rolling Thunder tour was, by all onscreen accounts, a true circus, including the sword-carrying valkyrie violinist Scarlet Rivera; Dylan masked in face paint and an ensemble of both a rogue and nymph out of Desolation Row; and experimental poet Allen Ginsberg, whose scenes have a soothing soulfulness that’s a welcome antidote to the first half’s frazzled nature.

Paramount to that circus feeling is the sense of chaos, and editor and regular collaborator David Tedeschi’s cuts don’t shy away from the ramshackle logistics shepherded by industry outsiders or Dylan’s own infamously mercurial mood. One memorable interview has regular Dylan collaborator Joan Baez reminiscing how the simple question of “Are you okay?” had a domino effect on Dylan, triggering a swell of temperamental energy and a cloud of doubt.

Undoubtedly an enormous undertaking as a piece of filmmaking, the footage collected here ranges from scenes from 1978’s Renaldo & Clara to a practically pristine digital restoration of a battered work print from 1975 that included much of the concert and b-roll footage. Conversely, certain recordings have previously been available in bootleg form (a colossal 14-CD, 148-track box set was released last week), but it’s not only a change in the audio fidelity–live favorite “Isis” is an easy highlight with its crisp, sloping guitar lines–that comes with these restorations. Taking place nearly ten years since Newport, this footage is rewarding for simply watching Dylan as a slippery stage performer.

Even at his most crowd-pleasing, there’s an anti-social dissonance and internal difficulty that’s only supported by the interstitial material. And Scorsese and Tedeschi aren’t overly precious about these performances, regularly cutting to interview digressions in the middle of songs but skillfully never neutering the implicit paranoia and smog that gives this film a welcome sense of danger.

It’s almost disappointing when the haze of the first half dissipates for a more reflective and conventional concert film. But even as it becomes something more familiar, it’s never anything less than tremendously entertaining, whether seeing Dylan’s wild, stalking presence on stage with one of the most full-bodied ensembles of his career, or listening to born storytellers like Sam Shepard discussing his aborted film about the tour. And while Dylan remains as amusingly guarded as ever about his past, other guests from the time are far more forthcoming about their own experiences and the strangeness of this musical walkabout.

Practically a school marm compared to her compatriots on the tour, the aforementioned Baez steals the movie with some of the most revealing insights about Dylan. A back-and-forth edit between her and a contemporary Dylan about their unrequited romantic relationship in particular is one of the most bittersweet and moving scenes. And a sort of intermission with Rubin “Hurricane” Carter offers a fascinating outlier in Dylan’s career in contrast with his usual opacity about his own lyrics and their meaning.

These diversions are nearly always thoughtful or add something to the understanding of the tour, but there’s still something of a missed opportunity. It’s a film that feels less like a concert documentary and more like a fiery missive. Scorsese and his production team have created an incredible document of one of the 20th century’s most complicated personalities, and one that feels close to being a great film.

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese hits Netflix and select theaters on June 12.