Eventually, we were going to have a movie about Julian Assange and his subversive WikiLeaks website, but is it better that we got the documentary before the biographical drama?

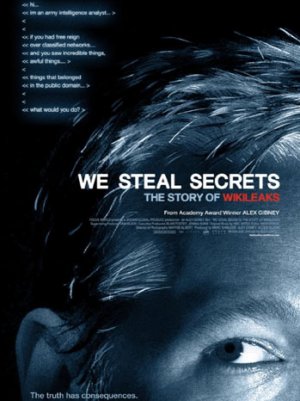

I think so; by the time Benedict Cumberbatch takes the screen as Assange in The Fifth Estate later this year, viewers will have a nifty, comprehensive reference in Alex Gibney’s We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wiki Leaks. Cobbling together scads of charts, reports, files, and testimonies, this venture feels most like an interactive article one might find on that other wiki site, the one that ends in ‘pedia’.

Gibney is part of the new fold of documentarians, molding reality with all the benefits and pitfalls that come with operating in a fast-paced, globally networked society. The most inherently troublesome of these challenges is finding a way to collect, interpret and assemble the same content that everyone the world over has already absorbed, digested and become an ‘expert’ on.

With films like Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room and Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God, Gibney operated more like a cinematic construction worker than an artistically-inclined observer; raising supports, measuring trajectories, improvising when the blueprints trailed off into obscurity, and patching any holes that would distract the critical eye. With We Steal Secrets, he finds himself in a similar mode but with the added challenge of giving some sense of meaning or emphasis to a story that has swirled around in popular culture long enough that the waters have grown considerably cloudy.

Ultimately, We Steal Secrets cuts through the hoary media muddle by becoming a portrait of two men central to the controversy; Assange, the honey-tongued, charismatic co-founder of WikiLeaks, and Pfc. Bradley Manning, the young, troubled man deemed responsible for leaking a dearth of military secrets to Assange. Although there was a time when both would have been (and in some cases, still are) vindicated by those truth-seekers eager to unfurl the misdeeds of government and un-checked military abuse, their individual lives have encroached on this image. Assange is currently hiding away in London’s Ecuadorian Embassy from rape charges in Sweden, while Manning is held by the U.S. Military and awaiting the final sentencing for his actions.

When Gibney is offering up the varied facets of these deeply-flawed individuals, the movie threatens to achieve something more than news reports or a fictionalized bio might; it teases a portrait of the truth that examines the recklessness and danger of what these men did right alongside their alleged idealism for doing so, and puts them on trial for the viewer. Ultimately, Gibney shies away from taking any stance, perhaps because he’s following a journalist’s good sense that he’s here to report and not to offer sentencing or allegation. Without that voice, though, we are left with the less convincingly righteous claims of these two figureheads, angling for understanding for what they did, but coming off to these eyes like two rebellious kids; one bucking a system for profit and the other because they felt goaded into it.

Assange would have himself viewed as a kind of Robin Hood of the information age, and to a degree, one can find it hard to argue with some of the info and images offered up by his site. There’s a certain sense of horror and betrayal that coincides with the clips that feature soldiers laughing while firing on so-called “combatants”, but then follow-up scenes show Assange’s vocal disregard for any lives lost because of his making public files that could compromise and expose national security. His attempts to incorporate his sexual crimes trouble in Sweden into the general outcry against him falls flat here, partially because Gibney won’t let the know details drift off-screen as some of Assange’s supporters have.

Although Gibney actually develops another view of Assange as he proceeds, finally allowing the man’s own avarice and contempt for any sort of authority to reveal itself, he seemingly paints Manning with a more positive brush. Of course, there’s info that suggests that the unstable young man’s primary reasons for doing what he did were less about the pursuance of truth and justice, but because his own aggressive outsider status—documented meltdowns, suicide threats, physical attacks, and bizarre cross-dressing correspondence—drove him forward, heedless of any repercussions. This dichotomy is what makes We Steal Secrets an interesting watch, and accounts for its basic success as a rousing depiction of a morally questionable situation. When the more compelling questions arise between the lines—what true responsibility, if any, does an individual have to their country’s sanctity while simultaneously opposing the practices of its government?—they linger briefly, before evaporating in favor of more glaring personal observations about Assange and Manning.

Thankfully, Gibney is so diligent in sewing every crumb that he finds into the overall patchwork, that Secrets retains its usefulness as cultural portrait, even if it ultimately never successfully addresses the more lasting social concerns that are dredged up by the WikiLeaks debacle. If you are a scholar who’s already parsed the facts of the case, examined the personalities, and desires a stronger critical dissection of the entire scenario, then We Steal Secrets may have little to offer you. If you vaguely remember the names Assange and Manning, and know it had something to do with security breaches and computers, then you may owe it to yourself to see this movie.

We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks is now playing in limited release.