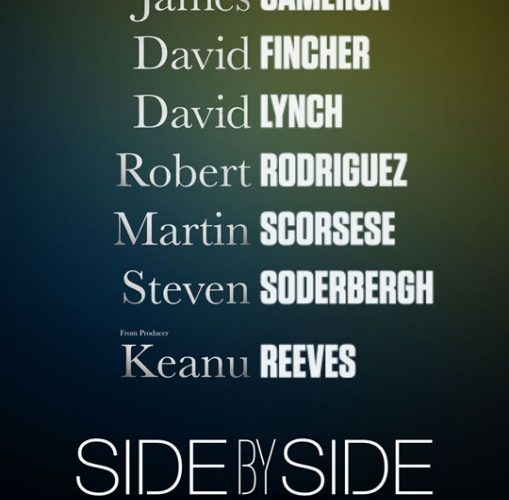

Christopher Kenneally‘s Side by Side is a comprehensive and diplomatic documentary about the ongoing combat between two feisty fields of filmmaking — the one, photochemical film, having been around since the medium’s invention, and the other, digital, still flexing its potential wings. The film, narrated by the calm voice of Keanu Reeves, premiered to open arms at this year’s Berlin Film Festival, and figuring out the reason for that is about as easy as figuring out why a midnight showing of The Avengers would play like gangbusters to a 13-year-old kid in a Hulk outfit.

That’s not to say there isn’t value in the process, because Side by Side is a smart movie, and it did teach me things. But the chief enjoyment is, without a doubt, the robust lineup of icons Reeves has been afforded the opportunity to sit down with. Because as informative as the bouts of educational voice-over are — on several occasions, we’re invited to learn the step-by-step technique of various aspects of the moviemaking practice — Side by Side is, first and foremost, as good as the insight of the artists put in front of the camera. Which is to say that, often, it’s quite good.

In fact, if there’s one area where Kenneally‘s management is singularly authoratative — as opposed to simply playing, mostly risk-free, to an eager audience — it’s the very way in which he structures the appearances of these artists, delicately balancing the pro-film honchos with the pro-digital ones. As easy as it would be for Kenneally to choose a side, he always stays true to his title, harmonizing the pros and cons of each method to a laudably open-minded effect.

Of course, to the primed viewer, Side by Side feels more like a bumpy roller-coaster than the honest, symmetrical instrument it truly is. After listening to a few minutes of regular collaborators Christopher Nolan and Wally Pfister elegantly mouth-off about the superiority of the film image, we’re all but moments away from wanting to take a sledgehammer to the existence of digital. But then people like James Cameron, Martin Scorsese, and Lena Dunham (admitting that, without digital, she may not have ever made the jump from writer to hands-on filmmaker) come along, and we suddenly want to berate the likes of Nolan and Pfister for having such a close-minded view of their decidedly creative profession.

Historically, the film is more well-versed, and more concerned, with the evolution of digital, and that’s nothing to complain about. While pessimists may go home upset about the lack of Eadweard Muybridge name-drops, the last thing we need is a forward-thinking filmmaker to bog his project down in tedious academic commitment. Instead, we get fascinating, specific insights into how the prospects of digital equipment have propelled countless filmmakers — some young and raw, some old and seasoned — to do things they wouldn’t have been able to do with only celluloid at their disposal.

We learn, for instance, how the haunting nighttime textures of Michael Mann‘s superb Collateral wouldn’t have been possible without cinematographer Dion Beebe‘s use of the Thomson Viper camera. We learn how Danny Boyle, while planning the opening of 28 Days Later, came to the epiphany that capturing a dead-empty London becomes a hundred times easier — and cheaper — with the use of digital techniques. (A few years later, Boyle‘s Slumdog Millionaire, shot by Anthony Dod Mantle, became the first predominantly digital production to win the Best Cinematography Oscar.) And we’re reminded of Robert Rodriguez‘s delirious Sin City, which wouldn’t even have been attempted in an exclusively film-oriented Hollywood.

Bits of trivia like this represent precisely what I like about the film. But they also, perhaps, represent a difficulty Side by Side may encounter in branching out of its ripe-for-cinephiles milieu. While the sight of a bearded Keanu Reeves, subdued but also on a mission, is a cool change-up to his general public image, I wonder what kind of crossover life Kenneally‘s film will have. In coinciding its theatrical debut with a VOD release, the film’s handlers are clearly adopting the film’s own progressive mindset — let’s hope it pays off.

Another of the film’s crucial voices is David Fincher, who, true to recent form, appreciates the exactitude and control he can have in the world of digital. It’s a measure of the film’s skill, as well as the uniqueness of its subjects, that Steven Soderbergh, an equally strong component of digital, appreciates his newfound tools for the entirely opposite reason — for the spontaneous, excitingly unknown energy they provide. In a terrific outtake, it’s Soderbergh who says, “We are, in essence, always at the beginning of infinity.” Someone tell me why that line didn’t make the final cut.

Side by Side begins its limited release this Friday, August 17th. It will be available via VOD starting on August 22th.