The young chef Masato, played by Japanese actor Takumi Saitô, gets home after a long day at the family-owned ramen restaurant that he works at. First, he tends to his father, who’s passed out drunk on the floor of his room, covering him with a blanket. Then, he opens a package that he’s received, filled with spices, which he uses in a chicken broth that he starts boiling while he watches a YouTube video on a Singaporean dish. Any doubts regarding the nature of Eric Khoo’s Ramen Shop are instantly cleared, as this isn’t just the listing of some character traits, but the body and soul of what it’s about: cooking, eating, ingredients, spices, flavors, and aromas.

Although the event that triggers the narrative’s main event is the death of Masato’s father–victim of a long depression and alcoholism–the film doesn’t stray away from its main focus. This isn’t a story about the rekindling of the relationship between Masato and his father (after all, he dies ten minutes into the film), but about finding a missing flavor, and that’s his reason to travel to Singapore, the place his mother was born and where he lived with both his parents until they moved to Japan, where his mother died very young.

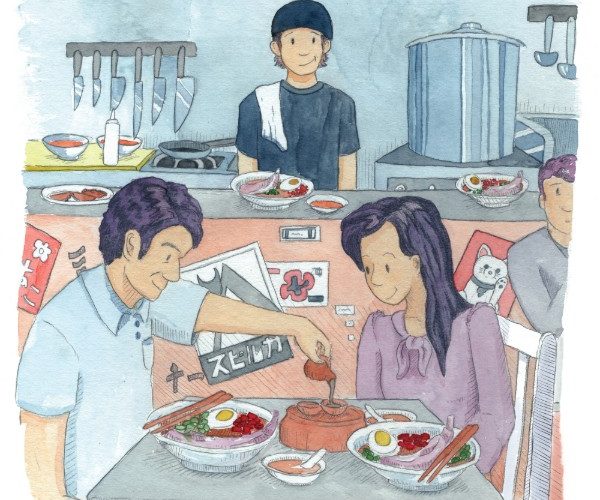

Masato’s travel might bring movement to the story, but the centerpiece is the variety of foods that can be found and the way that the director showcases them. In the film’s opening we see the oily broth with which the ramen is being made, the variety of colors and textures present in the food from Singapore in both street markets and restaurants, as well as a perfectly rendered flashback where we see how Masato’s parents met and how he cooked a Japanese meal for her consisting of bright delicious sashimi, spongy tamago, and a variety of delightful little dishes that beautifully describe the minimalistic nature of Japanese cuisine. May this serve as a warning: this film will make you hungry.

But the main dish that Masato is after is the pork-rib soup, also called Bak Kut Teh, a flavorful concoction made with a slowly boiled pork broth and pieces of pork-ribs submerged in it. To achieve the secrets of how it’s made, Masato is reunited with his uncle, the brother of his mother, who has a bak kut teh restaurant in Singapore. The film’s funniest sequences happen here, as they both speak English with very thick accents, trying to bridge the language and culture differences.

The film breezes through the drama that might otherwise be present when it comes to the estrangement between father and son, and later the one between the Singaporean side of his family and himself. Here and there, Khoo tries to insert mentions of the Japanese education of Singapore, which might be among Ramen Shop‘s weakest moments as they could be defined as “young Japanese man atones for his country’s sins by going to a museum.”

And that’s maybe because the film doesn’t really want to be about those separations, estrangements, deaths, and friendships. It’s mostly a very strong PSA for people to book a vacation in Singapore to eat all those meals, because even if some sort of conflict appears towards the last third, it’s solved and forgotten in an almost uneventful way in order to continue exploring the possibilities of Japanese and Singapore cooking. In that sense, Ramen Shop has its charms, but it’s a bit too lightweight to leave a lasting impact.

Ramen Shop opens on March 22.