There are few conversational taboos more likely to cause arguments than sex offenders. For some, the mere mention of their existence is enough to make blood boil, let alone the murderous rage that emerges within others when the subject even tiptoes around children as the victim. It’s a polarizing topic, and one that makes recent inquiries that bring out the humanity behind these people both scarce and important.

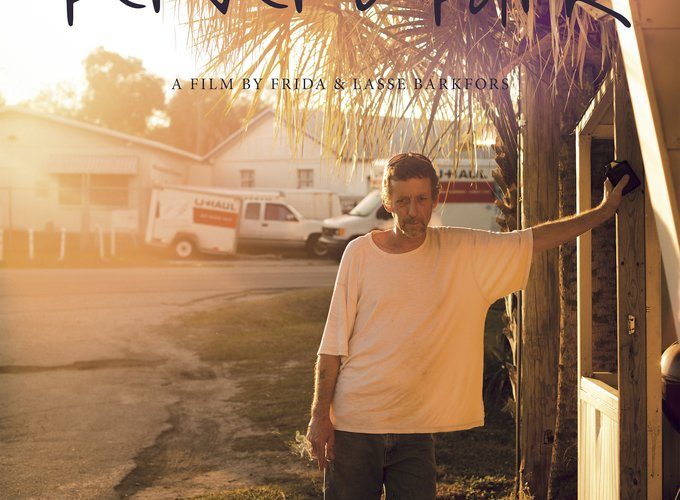

Even beyond the delicacy of the subject matter, it presents other difficulties in understanding people who are coming from a nearly endless permutations of factors, personal or otherwise. The best thing that can be said about Frida Barkfors and Lasse Barkfors’ documentary, Pervert Park, is that it doesn’t succumb to generalizations about its subjects, a small sampling of former sex offenders now living together in a community in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Known as the Florida Justice Transitions Housing Program, the neighborhood houses nearly 120 rehabilitating offenders. Every day, they work as a unit to become better people by coaching each other on their experiences and how to push away undesirable thoughts and urges. Overseen by a visiting therapist, Don Sweeney, some of the residents have been there for days, while others have been present for years. And the movie takes pains to identify the differing psychological profiles of those who just arrived and the veterans.

While “sex offender” has become an umbrella term, it can cover everything from flashing to pornography to molestation. But that’s not to say the documentary has an agenda in defining the severity of the individual crimes, nor an interest in softening their behavior with empathetic storytelling.

One of the interviewed residents has some plausible deniability about what he was engaging in, as he was entrapped by a police officer masquerading as a 30-year-old woman. In general, this is a documentary that’s unflinching in the face of hearing the stories of people who made life-altering mistakes. But they’re not painted as victims, and they’re not asking for forgiveness. Some of them came from a broken families with histories of abuse, and others came from sunny marriages that became too much, but the people themselves recognize that it doesn’t make them any less responsible for their actions.

Their individual stories are heart-rending, and also frightening in their mundanity as you hear tale after tale of people who become inundated with their own unhealthy impulses. The shared community setting provides its own surprising companion in understanding these characters. It’s notable that early on, when a relatively new resident is unsure about the origins of his desires, another veteran is quick to assert that he went through a similar period until he later understood what happened. Many of these people speak about their pasts as if they were subconsciously mapping their fates.

If anything, Pervert Park’s main goal is to recognize these people as real human beings rather than faceless pariahs. The movie doesn’t exonerate them for their past behavior, and while it does provide a chance for them to tell their stories, it’s not a glorification of their atonement. The subjects of Pervert Park are people who’ve scraped rock bottom over and over, and, in searching out help, they’ve regained some will to live. They’ve betrayed those who are closest to them, and perpetuated cycles of abuse.

Against the muggy backdrop of Florida and an environment that feels true to the tropics in its nocturnal bleariness, the documentary has an evocatively stuffy environment, but there is a certain lack of focus herein. Rather, the structure is more often just following a character for a set time until they tell their story, and then moving on to the next person. There’s an appealing sense of cyclical healing in watching these people go about their daily rituals; in the end, however, Pervert Park feels like an incomplete portrait of this tight-knit community.

It might just be a case of a lack of access or not enough footage, but Pervert Park lacks a larger centralized thread whether it’s speaking to people more about their experience talking to outsiders or looking into the conflicts that arise in a community such as this. Pervert Park‘s subjects know that things might never be the same, and the documentary raises a similarly complicated question: why has the stigma around sex offenders stayed the same?

Pervert Park is now in limited release, playing at IFP’s Made in NY Media Center.