The morning of August 4, 1892, Lizzie Borden discovered the bodies of her father and stepmother who had been axed to death in their house. She went on to become the prime suspect in the murders, and even though she was eventually acquitted, history turned her into a folk tale used to instill fear in little children who shudder at the idea of her cursed axe. How could it not? After all, Borden became the embodiment of everything a woman was not supposed to be: wealthy, outspoken and unmarried.

In Lizzie, director Craig William Macneill and screenwriter Bryce Kass don’t attempt to further acquit her, but sticking to the idea that Borden indeed murdered her parents, they create a feminist case for her. Not that murder is justifiable of course, but rather than focusing on Lizzie as a figure out of a horror movie or creepy folk tale, she is portrayed as a woman who found liberty only through the death of her oppressors.

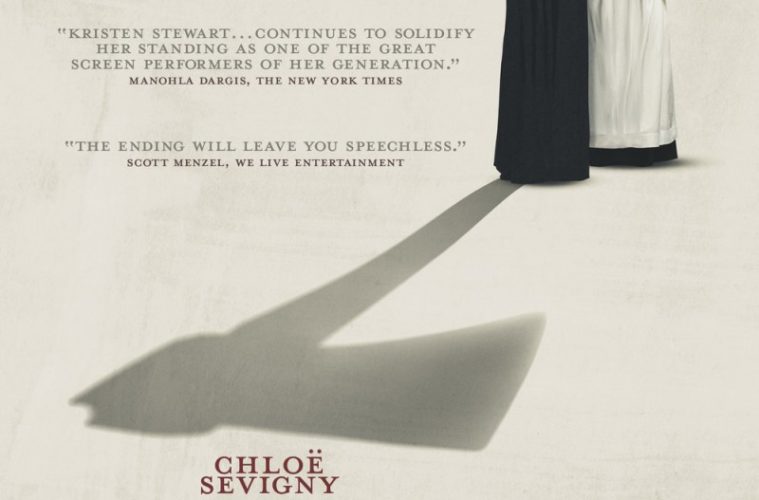

As played by Chloë Sevigny, who actively sought to have the film made, Lizzie is a woman out of time. She’s not anachronistic by any means, but infused with Sevigny’s sophistication she becomes a creature trapped in a present that feels too much like the past. When she announces to her father Andrew (Jamey Sheridan) that she will go to theater unaccompanied, she doesn’t do it for the thrill of the scandal, but simply because she is so bored at home that the idea that she needs a man to take her out for entertainment doesn’t deter her from challenging the system. To show Lizzie’s self-awareness, immediately after her father concedes and asks her to be home by midnight, we cleverly see Lizzie out in the street on her own, slightly hesitating knowing that unfortunately her world, and ours, is still largely unsafe for women.

Lizzie finds a kindred spirit in Bridget (Kristen Stewart), their newly arrived Irish maid, who despite her lack of education–or perhaps because of it–speaks truthfully to Lizzie, allowing conflicting feelings to arise in her. Unbeknownst to Lizzie, her father has also set his eye on Bridget and she becomes an element of contention between the two.

Mr. Borden runs his house like a drill sergeant, keeping his daughters (Kim Dickens plays Emma Borden) and wife Abby (Fiona Shaw), living in the dark ages–quite literally, as he’s one of the few people in their small Massachusetts town who refuses to upgrade to electric lights. “Father doesn’t believe in light” declares Lizzy to a nosy stranger who questions her about the darkness of her home. Lizzie’s response, as rich and full of meaning as every frame in the film, shows her to be a woman who can no longer defend the system she’s been born into–not only as a Borden family member, but as a woman.

Even though Lizzie and Bridget begin a romance, the film doesn’t reduce them to forbidden lovers in search of a better future, but rather as people who find themselves enslaved and tormented to the point where taking someone’s life seems to be the only way out. The film doesn’t obsess morbidly with the way in which Lizzie planned the murders; instead it shows them as something akin to a ritual experience. Completely naked, for both practical and ritualistic reasons, Lizzie first goes for Abby, and while not necessarily giving her a merciful death, she appears to know that in a way she is also setting this woman free. One of the most striking moments in the film comes when after killing her father, Lizzie places a pillow under his head. Even though history suggests Lizzie did this in order to pretend her father had been ambushed while he was sleeping, the film shows a daughter granting her father one last grace. It’s an unexpectedly tender moment in a film dealing with less than delicate people.

Much of Lizzie’s success is owed to cinematographer Noah Greenberg, who takes advantage of natural light to lay it all bare. Daytime scenes are delicate enough without being bucolic, while nighttime moments are captured faithfully, making us understand why Lizzie found her home’s darkness to be claustrophobic. Greenberg also frames the characters in ways that the visual language adds to what’s not being said. We go from early scenes where Lizzie is always captured from behind to others when she appears on the edge of the frame, almost as if she was afraid to take her rightful place in her own narrative.

Lizzie is being released in theaters during a week where we’ve seen Serena Williams being blamed for an umpire’s disdainful decision, and where we’ve seen pop star Ariana Grande being harassed by “fans” who blame her for her ex-boyfriend’s death. Women continue being blamed for the sins of men, so it’s perhaps not a coincidence that the film is arriving at a time when its call for equality is as urgent as it was in 1892. If nothing else Lizzie should elevate Borden’s story from a folk tale to a century’s long cry for justice.

Lizzie is now in limited release.