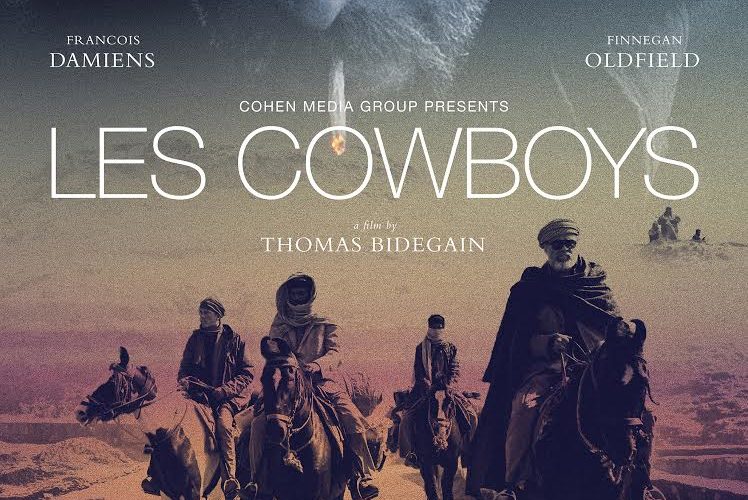

Excepting the chance that some very obvious parallels went over a critic’s head, there’s nary a review of Thomas Bidegain’s Les Cowboys that lacks mention of John Ford’s The Searchers, so let’s lay those cards on the table before going much further. The cowboy-led search for a girl kidnapped by Native Americans in the American west circa 1868 has been replaced by a father-son pairing (François Damiens and Finnegan Oldfield, respectively), a willful runaway, Islamists of (it-seems-purposefully) vague nationality, a mixture of European towns and (it-seems-purposefully) vague Middle Eastern terrain, and more-or-less-contemporary surroundings. What are we left with? Old and young men, prejudices against a dark-skinned other, the wonders and horrors of unknown land, and an unknowable woman at the center of every component.

Les Cowboys is not as fine a film as The Searchers much in the same way most ever made are not as fine a film as The Searchers — Bidegain and Damiens would probably understand when I say that mostly comes down to Ford and Wayne, separately and together — and the differences become so pronounced as to make clear that it’s not aiming for equal placement, or at least not in ways I can detect. Though he doesn’t set the action precisely in our current day, Bidegain’s anxieties, sense of “relevant issues,” basics in formal expression, and delineation of information shape this men-on-a-mission template with thoroughly contemporary means. Consider its establishment of the young girl’s disappearance, a scenario that encapsulates so much of this movie in one go: as elegant in the particulars of its visual schema — from a nicely placed American flag in the title card to sun-streaked forests to quick cuts that ratchet-up tension — as it is blunt in drawing cultural lines, i.e. individual scenarios wherein these French dress like cowboys and sing “Tennessee Waltz” while these Muslims sit in low-lit rooms containing offerings of dates and tea. Thinly drawn, sure, but very much of a certain moment.

They’re part and parcel of a narrative structure that favors immediate moments by cutting nearly every scene, even ostensibly more tender exchanges between friends and family, down to the essentials of conversational exposition. There’s more success in plotting than much else: with a phone call, a command, an address, and a contact, father and son are on the move and Cowboys‘ story advances efficiently, quietly, with determination towards a basic goal of finding one person — a progression more gripping, perhaps, than the overarching story to which it’s been attached. Fitting, then, that Damiens’ screen presence, a brewing intensity that this character is just smart enough to hold back — until, of course, he isn’t — and the visual forces at work (i.e. Bidegain and DP Arnaud Potier) are what make a thinly drawn figure into something of note: this is a work of bits and pieces that cohere into a whole only somewhat greater than admirable parts.

Larger ambition presents itself at precisely the halfway mark (if we’re not counting what runtime’s afforded by credits) as Les Cowboys shifts towards a (somewhat) new figure, a new location, and a new timeframe without changing the mission at hand, neatly combining the overriding drama with untapped atmospheric potential. Would that it lived up to the promise of such a gambit, which Bidegain and co. falter in lending the sort of narrative and emotional gravitas they’d been building towards before boldly cutting this film off right at the head. Among other things, a surprise John C. Reilly turn, over almost as fast as it began, is hard to take as seriously as it’s clearly meant. Many questions arise, chief among them obviously being this: how to maintain a straight face when this (otherwise very fine) actor sincerely warns our new protagonist not to mention “Taliban, bin Laden, Al-Qaeda – none of that shit”? (“Obviously” because I can’t stop puttering around with those words under my breath.)

And what to make of the way Les Cowboys handles its non-white characters? Though generally ill-equipped to tackle this too directly, I nevertheless find it necessary to consider the role most are given — as shouting, advancing enemies either on the cusp of a violent act or engaged directly in it, and / or shadowy figures either aiding or among an ominous faction — and the fact that perhaps the sole Muslim figure with a major role is a woman saved by her white fellow prisoner and eventual object of romantic interest. In the year since this picture’s premiere, some have, as they very well should, raised these questions. With my own limits in mind, I’m more gripped by this central point: that the missing desires to lead their new life — a rarely addressed fact that hums under the surface of every scene and any mention of them, and precisely the sort of detail critical enough to a work’s meaning for it to be missed or misconstrued.

For those who also find their interest waning as the narrative shifts from an intriguing, globalized detective tale to a single-person-centered exploration of inhumanity, these details make the investment into Bidegain’s film essentially worthwhile. Will it change my consideration of European-Islamic relations? No. Have I thought about its moral quandaries in the days since seeing this film? More than most others, at least. Does Les Cowboys create an itch to again see The Searchers? Absolutely — and that alone is a fairly strong end result.

Les Cowboys will enter a limited release on Friday, June 24.