It is not before the two-minute mark when we realize that, in Crystal Fairy, something is different about Michael Cera. His feeble, awkward-sad stylings have, by now, become inextricable from the actor’s own public identity, with seemingly every project presenting audiences a take-it-or-leave-it offer before the first shot has been projected onto a screen — player and part always unified into a single whole for the paying mass. But as the film begins with a camera making its grainy, bobby track through a crowded house party, there are already glimpses of a different performer, one with an extra helping of cocksure and more physical sturdiness. By the time he’s snorting cocaine in a backroom, inquiring about the drug’s national status, that well-worn notion of player and part have finally been shattered and reconfigured into something else — simultaneously familiar and divergent, always holding our attention.

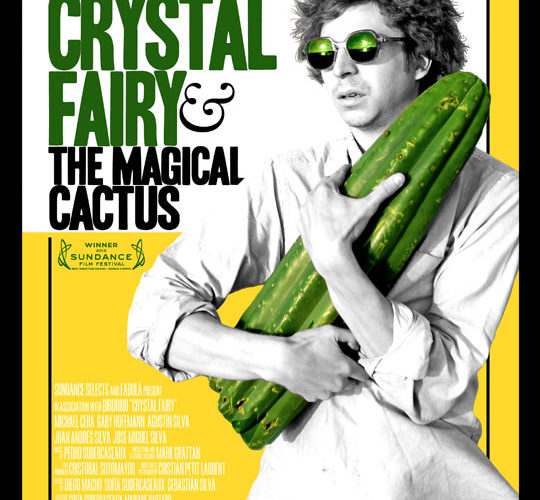

It’s to both the credit and fault of writer-director Sebastián Silva that his feature — in trippy opening credits, going by the full title of Crystal Fairy & the Magical Cactus and 2012 — would position itself as a center stage for the utterly unconventional, with little else in the way of expected or, much less, ordinary specifics. As a picture predominantly aimed toward the insecurities of its characters, Crystal Fairy, in order to play as more than simply a noble effort — in order to transcend some familiar points, too — winds up more or less dependent upon consistent, engaging psychological profiles; Silva’s decision to have the small cast improvise their dialogue has robbed it of some greater value once all is said and done, however. There’s a sense that high points, such as they are, only get reached on occasion, and more often than not for the same reason: the work of Cera and his co-star, Gaby Hoffmann, the latter of whom puts in a go-for-broke performance as the titular fairy, an emotionally exuberant hippie tagging along with four young men seeking a drug trip on the Chilean beach.

Positioned as solo and one-versus-one turns, they could be watched for hours on end. Positioned as the central characters of a dramedy that, in its brisk runtime, strives to cover male voyeurism, gender-based insecurity, generational irresponsibility, and even some of overseas American brashness, Crystal Fairy winds up a piece of work that’s only of intermittent engagement. Events proceed at such a jagged pace — in the middle section, especially, where points move from scene to scene with little help from customary transitions — that this writer found himself eventually waiting, idly, for one thing to happen after another, increasingly disconcerted by the feeling that events may leads nowhere.

By the halfway mark, when our five characters reach the shore and have begun to indulge in their mythical cactus drug, some might expect that conflicts established beforehand would bubble to the surface — but they don’t, exactly, because Silva is more concerned with the peculiar rhythmic boredom found in spending time on the beach; how it might truly affect a two-person relationship, as seen between Jamie (male) and Crystal (female) — instead of simply one — can resonate as a secondary matter for much of the runtime. But although it’s not necessarily the preferable way to tackle ideas which have been springing up — no less when their introductions don’t have great spark to begin with; some are “resolved” by virtue of, simply, no longer factoring into the action — the progression sees us witness to storytelling methods which, in all fairness, are hardly inconsistent with the strategies employed thus far. A mark of coherent structure, if little else.

Turns are, nevertheless, what Silva has used to guide this dive into repressed gestures, and Cera & Hoffmann’s turns really are the thing. By now it’s been widely noted that Fairy’s titular lead bares all for a number of minutes — Hoffmann having entered the public spotlight as a child (most memorably seen in Uncle Buck, Field of Dreams, and Sleepless in Seattle) will, for a hopefully select few, only bolster “discussion” — though it’s almost bound to miss that we’re seeing nakedness with purpose: Silva is wise enough, as both a plotter and shooter, to understand that it ought to be the circumstances behind nudity which compel, not simply the sight. Methods by which his script delves into the character — from textual droplets of information to unclear personal motives — are a treatment of such worth that, for as fine as Cera is, dramatic tenor would’ve been more strongly maintained had Crystal Fairy herself been kept in the picture to greater lengths, a sensation further emboldened when Hoffmann deftly supplies the picture with its emotional climax. (Though, to his credit, Silva imbues the scene with discovery and wonder, placing his actors in a pitch-black environment and illuminating little more than a face with campfire.) To observe Jamie indulging in his psychedelic substance of choice doesn’t hold the same water; blame it on the fact that cinematic drug trips, regardless of craft applied therein, are on the whole a disengaging item to witness.

So if there’s any concept which steadily carries itself to the finish line while, still, leaving open-ended questions for an engaged participant, it’s that theoretical classic, “male gaze” — not exactly a fresh territory all its own, of course, yet never bit off in quantities greater than what Crystal Fairy is capable of chewing, either. In no small part because of its willingness to only commit to a few select themes, no matter how many are initially present, this is a film of pleasantly curious choices and operations — the result of parts occasionally superseding the whole without individual components managing to overpower a final vision.

And it’s rather nice that someone, anyone, made an attempt to explore modern male pathology without succumbing to easy delusions of grandeur. As a trip movie more focused on journeys of the mental shade than the physical, Crystal Fairy is all about that uneasy destination: never in sight but always on the edge of perception.

Crystal Fairy will open in New York City on Friday, July 12th.