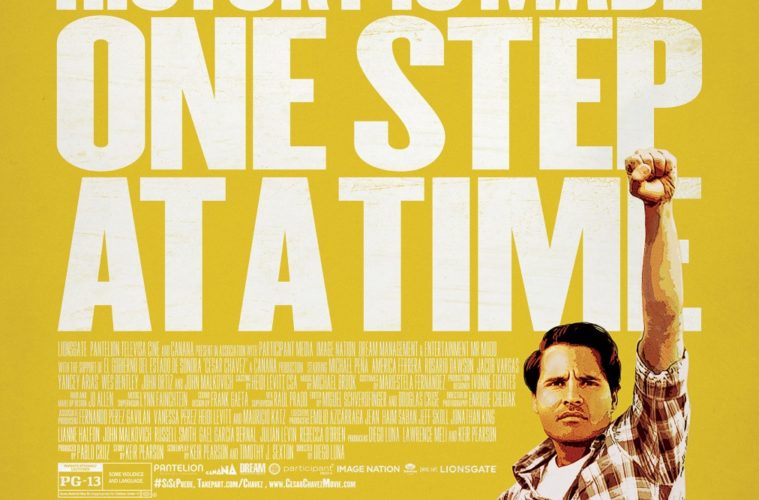

Diego Luna’s Cesar Chavez is an entertaining history lesson, but not quite an exact biopic; the story restricts its focus to a five-year period, ending with the negotiation of an agreement between the National Farm Workers Association and a collation of grape farmers. At the bare minimum, the story offers a simple and inspiring model for social change at a grass roots level. At first, a protest movement isn’t so much a negotiation as it is an effort to call attention to a complex set of problems. Luna’s film simplifies those challenges, sometimes to a fault – consider Wes Bentley’s brief appearance as Jerry Cohen, a lawyer for the NFWA who lacks character development.

Then again, this is not his story, as the film is squarely focused upon the Chavez family, including Cesar (Michael Pena), his wife Helen (America Ferrera) and son Fernando (Roberto Sosa), and particularly, the movement they create. Moving from Los Angeles were Chavez works in office organizing labor, he quite literally engages in fieldwork, working undercover in Oxnard. Returning back to his family in Delano, California, he unites Mexican and Filipino farm workers all while annoying the local Sheriff (Michael Cudlitz). The NFWA builds an infrastructure for the works, including starting a credit union at the Chavez family, run by his wife and sister-in-law Dolores Huerta (Rosario Dawson).

After the sheriff’s tactics, including turning a blind eye to crimes committed against the protestors, capture national attention via senate hearings led by Senator Robert F. Kennedy (Jack Holms), Chavez’s movement gains more traction. They move towards their largest target yet, grape producers, by encouraging a boycott of wines and table grapes. And thus we’re introduced to the opposition, a complex villain in the form of John Malkovich’s Bogdanovich, a farmer who built his own business by hand. After striking a deal with the Nixon administration, he exports his grapes away from the plummeting US market, and the film provides ample evidence that both Nixon and Reagan were anti-labor.

The Cesar Chavez story is worth telling, perhaps in a longer form mini-series like Olivier Assayas’ Carlos. As Chavez’s movement turns violent, there’s a sequence that could have made for a film of its own, as he challenges himself to a hunger strike; so could his relationship with his son, and countless other elements that deserve richer storytelling than director Luna and screenwriters Keir Pearson and Timothy J. Sexton give it.

For better or worse, the film is a call to action, but I want to know more. Its studio, Participant Media, often makes entertaining, engaging narrative features and documentaries that end with a link to a website to “learn more,” but I suppose the problem is this film tells us too little, compacting a longer story into 100 minutes. The ends are tied up too neatly, using title cards that tell us this strike, a larger action, was just a smaller moment in a life well lived. Regardless, it should go without saying, Luna’s film underscores the drastic need for more Latino-centered historical narratives.

Cesar Chavez is now playing nationwide.