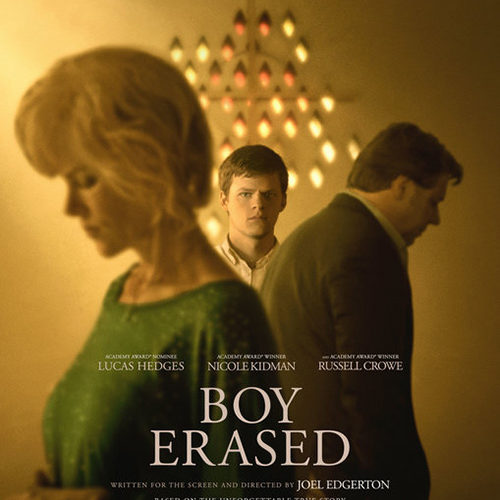

Few images might conjure as much terror and dread as seeing two Baptist church elders entering your home in the middle of the night. It’s precisely what Jared Eamons (Lucas Hedges) sees shortly after coming out as gay to his mother Nancy (Nicole Kidman) and his pastor father Marshall (Russell Crowe). Making his way to the kitchen table where the adults have been discussing how to solve this new evil, the young man is asked a crucial question: is he willing to aid in his own salvation by finding a cure for his malady, or is he ready to leave home and indulge in his sinful “chosen” lifestyle?

We have already learned the answer as the film begins with Jared, accompanied by his mom, en route to attend a gay conversion therapy program ran by Victor Sykes (Joel Edgerton). A character straight out of an X-Men movie, he seems to get a perverse pleasure out of trying to reform young queer people by finding creative uses for the Bible. The Holy Book is used to literally beat the devil out of the teenagers at one point, and he subjects them to endless psychological abuse, including boot camps led by the vicious Brandon (Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers in full Clockwork Orange mode) on how best to be “masculine.”

Since Boy Erased is based on the memoir by Garrard Conley, we know Jared will be alright. We know he survived and got to tell his story. And of course, as audience members and decent people, we’re relieved to know things will turn out good for him, but that makes the film completely anticlimactic as a piece of dramatic storytelling. It doesn’t help that as a director Edgerton has forgotten to give his film a point of view.

At a recent screening at NewFest, Edgerton introduced the film by explaining that he’d only come across Conley’s autobiographical book a year and a half ago, and he knew he had to make a film as quickly as possible. One can feel the rush, because as well made as the film is, it feels hurried to the point of being completely impersonal. It’s not an afterschool special necessarily, but it’s a film that falls into the trap of both sides-ism. One doesn’t need to be an exceptionally sophisticated filmgoer–or, again, just a decent person–to understand that human beings are never completely good or evil. Edgerton understands this too, but he over-digests it for his viewers by trying to make almost every single character palatable enough to placate the side they might offend.

Queer characters become completely asexual, to the point where one wonders if they have ever felt desire. Jared is so passive as a character that it’s a miracle Hedges got anything out of him. He spends most of the film observing, being subjected to events rather than leading them. He’s almost saintly in the dignity with which he suffers. Other than a terrifying scene of sexual abuse, which appears out of nowhere and fills the film with a devastating sense of anger and sadness that Edgerton quickly transforms into a facile lesson, a driving emotional connection throughout is mostly absent.

Religious people are also relieved of any responsibility, with Edgerton suggesting that they’re all only a-young-queer-man-escaping-torture-to-tell-their-story-and-change-their-hearts away. This is never more obnoxious than when he absolves Sykes by revealing his future in a title card that appears before we see the real-life people portraits near the credits. The revelation made my audience laugh out loud, but it bothered me to watch a movie that thinks evil can be justified if you’re a repressed human being.

Boy Erased would’ve been a better film if it questioned rather than just depicted. As queer and trans youths in America and all over the world are under constant attack by their governments, religious zealots, and other hateful groups, art should take stronger stances. Not everyone can be as lucky as Jared or as Conley was in real life. Not everyone gets to escape gay conversion alive. But in order to remember that, people need to accept that queerness is merely an aspect of a person. And as any other kind of person, queer people also have flaws and desires.

It’s perhaps no surprise that the stand-out of the film is Kidman, who transforms Nancy from a trophy wife into a fully realized human being because she allows her to feel everything the film is denying Jared. We see her desire for her husband, her motherly love for her son, and in scenes that are as frustrating as they are tender, we see her inner struggle, even when the dramatic device being used is having the character speak to herself.

Her loud delivery of “shame on you” to Edgerton’s Sykes followed by an almost whispered “shame on me” is the film’s most human moment. Kidman understands that change springs when the pain of staying the same is unbearable, when words come out of your mouth almost against your will, when your heart begins the revolution that shifts your brain. It’s a shame the rest of the film prefers to remain civil as the world slowly burns to the ground.

Boy Erased opens on November 2.