Repression is wild insofar as our minds pushing trauma down to the depths of our soul without a second thought. While guilt will ravage some to the point where certain actions become inescapable no matter what is used to numb the pain, others can completely detach themselves from the same memory. They will justify that they weren’t involved — innocent bystanders helping a friend who got in too far over his head. They fashion themselves as heroes whose karmic stockpile is cleansed from wrongdoing and thus renders them able to carry on as though nothing happened. Years go by and they forget it in a haze, merging that horrific event with the good times until unwittingly stumbling back as though called by their consciences to receive their long-awaited penance.

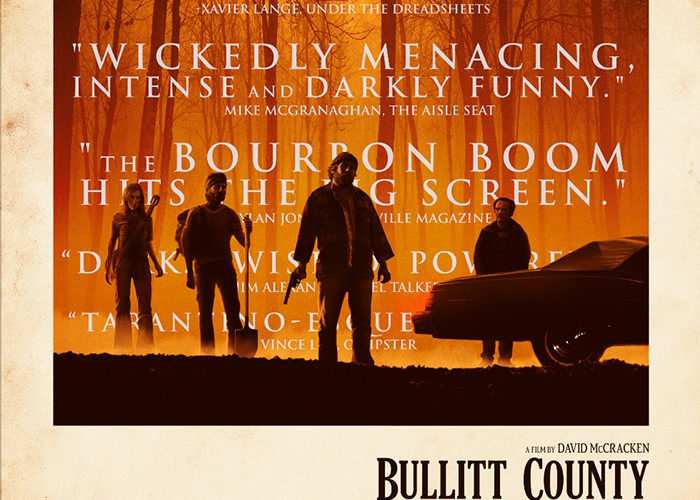

This notion of fate evening a score lies at the back of David McCracken’s Bullitt County even if we aren’t aware at the start. The filmmaker does well to introduce his characters as a zany quartet of old college chums who’ve grown apart and now find themselves facing an auspicious enough occasion to reunite: Gordie’s (Mike C. Nelson) bachelor party. So Keaton (McCracken) and Robin (Jenni Melear) stage an elaborate kidnapping to extricate their unsuspecting friend from his home while the always-nonplussed Wayne (Napoleon Ryan) looks on. They’re attempting to add some good-humored spice to a weekend that sees them ten years older than their last crack at the Kentucky Bourbon Trail. And it works until Gordie’s demons resurface — a reality exacerbated by the fact nobody else’s do.

What those demons are, however, remains to be seen. Sharp flashes of recall arrive every once in a while, but nothing with any true weight until well past the mid-way point. All we know for certain is that Gordie has been sober the entire decade since and that his BFFs either forgot or didn’t care when inviting him on a pub-crawl in his honor. You can’t therefore blame him for pulling the “groom card” when a blast from the past (Alysia Livingston’s Carolyn) relays a legend of buried treasure in the forest this foursome was planning to camp in anyway (hotel prices are for suckers). Rather than grow depressed while drinking water amongst the revelers, they journey past “no trespassing” signs with shovels in-hand to strike it rich.

Before leaving civilization behind, though, we must catch a glimpse of the darkness lying dormant behind these smiling faces. It comes courtesy of chauvinistic bar patrons aggressively hitting on Robin only to be met by Gordie’s unhinged wrath. The aftermath leaves them in a weird place as she tries her hardest to explain to him that what he did was just as bad or worse as what she had to endure from those strangers. It’s as though a flood of memories return to expose the destructive strain that kept them all apart. The possessiveness on display matched with the unhealthy self-appointed status of savior forces us to hold Gordie with necessary skepticism as his “good guy” act dissolves to expose entitlement, rage, and unpredictability. Expectations are instantly discarded.

While this is great in an overall sense of enjoyment through hindsight, McCracken may have waited too long. Our image of these characters is reversed on a dime after a tense encounter with the kindly Mr. (Richard Riehle) and Mrs. (Dorothy Lyman) Hitchens and the severity of that shift ultimately feels artificial as a result. This is less a slight on the performances (each actor does well to reveal his/her complexity in selfishness, survival, and desire for retribution) as it is on the structure. By holding off the pertinent flashbacks for such a prolonged period of time, we start to solidify who these people are in our minds. To then have them break those assumptions afterward makes it convenient to the filmmaker rather than the characters themselves.

It’s one thing to see tempers flare due to ideological impasses and another to witness how everything we thought was a lie. I honestly resigned myself to thinking a large portion of the film was about to be revealed as a nightmare or the manifestation of an unwell mind — that’s how far off the beaten path McCracken takes them. Bullitt County almost becomes two separate entities in the process, one half comedic romp and the other a bloody depiction of human nature left festering. The second part is vastly more interesting and yet it’s not given enough room to breath considering we already spent forty-five minutes languishing in false exposition. Only when we experience their shared tragedy do their current selves make sense in comparison to that idealistic nostalgia.

What McCracken supplies during the final thirty minutes is a short film unto itself with relevant psychological import. We’re watching these friends unravel to show who they really are and always have been. McCracken may be too quick to shine Keaton and Robin in a damning light that doesn’t take into consideration the intricacies of their involvement in what happened ten years ago, but they do prove complicit enough to let his train of thought continue where it goes. In the end, though, those two are here to ensure we see Gordie’s truth through pain. While his character is inevitably irredeemable, Nelson’s performance allows us room to sympathize with him regardless. More gratuitous betrayals send him overboard, but the weight they let him carry alone pushed him to the edge.

Bullitt County opens in limited AMC Theatres release on October 26th.