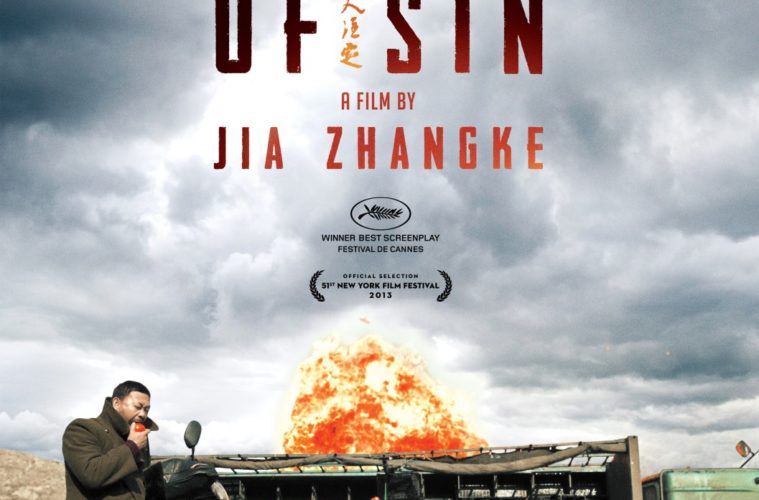

It has been five years since the release of Jia Zhangke’s last feature-length fiction film, 24 City — by far the longest gap between such features in his career. At first glance, one might think that the other Jia — he who gave us deliberately paced, documentary-esque pieces of overt social commentary, such as Platform and The World — has departed. The helmer’s latest, A Touch of Sin, is cleanly divided into four sections: each is about half an hour, and each contains more action in its own span than most other films do in their entirety. Indeed, the first scene sees a man thwart a gang’s attempt to mug him with a swift draw and accurate gunshots, rather cleanly setting the stage for what’s to come. A Touch of Sin is an action film by Jia’s standards, but the wuxia conventions are alive and well from beginning to end (the title itself is a reference to the genre classic A Touch of Zen), and that, alone, makes this departure about as sharp as the one Wong Kar-wai took with The Grandmaster earlier this year.

This is to say that, on the surface, it’s quite different: there is a great deal of violence, action is stylized, pacing is much faster, and shot lengths are considerably shorter. Beneath that, though, the same themes are visible. Just as Wong’s film was, at its heart, a difficult romance constantly threatened by changing times and China’s complicated history, Jia’s film serves as the examination of a change this same nation is currently forced to endure. Normally, Jia’s subject is westernization — that topic having been coupled with everything from artistry (Platform) to teenage ennui (Unknown Pleasures) — but this time he’s chosen violence, more than warranting the stylistic shift, and those who look beyond the genre elements are, once again, rewarded with a rich look into a culture that, 13 years after Jia chronicled generations of change in Platform, is still rapidly evolving. Even the geography and actor roles are consistent with his filmic world, as Marie-Pierre Duhamel explains in a wonderful piece for MUBI. With some closer investigation, it becomes clear that A Touch of Sin isn’t at all a departure.

The four stories present differing motivations for violence. First is the sometimes-reckless killing spree of Dahai (Jiang Wu), a vigilante out for economic justice. After failing to fight corruption the right way (people either refuse to believe him or simply don’t care enough to join the cause) and receiving a beating for even trying, extreme methods become the finest option. Dahai gets more than a little carried away — and some casualties are much harder to justify than others — but, here, Jia’s rigor pulls through once again: these murders are graphic and brutally loud, which couples shock with repulsion and condemnation. But when the victim is a man beating a horse for no apparent reason, we see no blood and hardly hear the boom of a gun; after less-agreeable murders, this one acts as a response to morally repugnant behavior and, thus, is not shocking or gross so much as it is outright funny. One interpretation might be that not all violence has been created equal, as the subsequent chapters would suggest, but another is that the murders prior happened to be just as acceptable; they were, in the eyes of the perpetrator, last-resort actions carried out in the name of social justice.

The next three acts show us violence in the name of power and greed, violence as self-defense, and violence against the self. The script — which constantly refers to different provinces and towns spanning from the north down to the south — firmly maintain A Touch of Sin as a work of social documentation. Likewise, as the film travels south across mainland China, it also travels across seasons, emphasizing that these forms of violence percolate throughout Chinese society. If “going south means heading toward the ‘modern world,’” as Duhamel suggests, then A Touch of Sin loudly argues that the modern world has its own problems with corruption and violence.

Indeed, violence against animals is repeated against humans, as if we treat one another like beasts, and the film’s narrative circularity — through which Xiaoyu (Zhao Tao, Jia’s frequent collaborator and real-life wife) finds herself in the aftermath of an earlier story — suggests that China’s economy is governed by violence, nepotism, and corruption. Still, the haphazard nature of these actions — the morality of which is not progressive, but random — can make A Touch of Sin a tad too opaque, and Jia’s purely observational style is far less cathartic here than in his previous features, as a number of motifs, from violence to geography to animals, are nearly impossible to discern on the film’s own terms. For all its provocations, A Touch of Sin can lean a bit too far toward senses of uncertainty.

Thankfully, cinematographer Yu Likwai — another longtime collaborator — effortlessly adjusts to this new style, making even the most violent scenes beautiful. These wuxia killings — the highlight of which is a beautifully stylized retaliation from an abused woman — elevate A Touch of Sin into the territory of great revenge pictures, even as its ideology proves less than discernible; for that reason alone, what we have may be Jia’s most accessible work, but the careful framing and editing that matches cuts to abrupt changes in soundscape prove to be the real treat. If Yu’s step away from long takes and documentary aesthetics wasn’t so seamless, Jia’s wouldn’t have been, either. How fortunate for us that the two have created a different kind of provocative political text without hitting any of the expected road bumps.

A Touch of Sin screened at NYFF and is currently in limited release in NYC.