What do you need to survive? It’s a common question we all ask ourselves — one that goes beyond the basic tenets of food, water, shelter, and human interaction. I’m talking about the things we cherish enough to put them before everything else. It could be freedom, hobbies, love, or art. It could be a feeling achieved by one specific song sung in one specific place. These are what we cling to and wrestle with when confronted by change because losing them is a sacrifice not easily made. But that choice is often out of our hands because allowing something new into our lives generally means giving something up whether through a financially driven decision or a cultural one. Maybe a necessary compromise is made that we’ll ultimately regret.

For Mi-so (Esom) it’s cigarettes and whiskey. They’re what brought her joy in youth and therefore also remind her of that period in her life no matter how far-removed she becomes. They remind her of old friends and band-mates that used to stay over until all hours of the night in a haze of drunken smoke. Wanting for nothing and seemingly immortal, these six souls were inseparably united by music, fun, and excess. But life eventually caught up with them. Careers were coveted and families formed. Responsibilities pushed frivolities to the fringes until their core identities seemingly changed overnight. This led to an inevitable drifting apart as safety and security trumped spontaneity. They woke from their dream and discovered reality isn’t quite as perfect as it they hoped.

Writer/director Jeon Go-Woon’s debut Microhabitat does nothing to soften this blow as she introduces Mi-so’s struggles straight away with pathos and humor. A freelance housekeeper barely scraping by with enough to purchase the aforementioned necessities alongside medication (for an unexplained ailment) and rent, she asks to borrow some rice from a client only to have it slowly escape her trash bag in a trail of birdfeed during her walk home. As for her current accommodations: they serve her needs as long as she wears five layers of clothes to combat the conservation of heat. This makes winter visits from her boyfriend (Ahn Jae-hong’s Han-sol) awkward yet sweet — his singular hope is to eventually afford a house together and alleviate this struggle. And then the rent goes up.

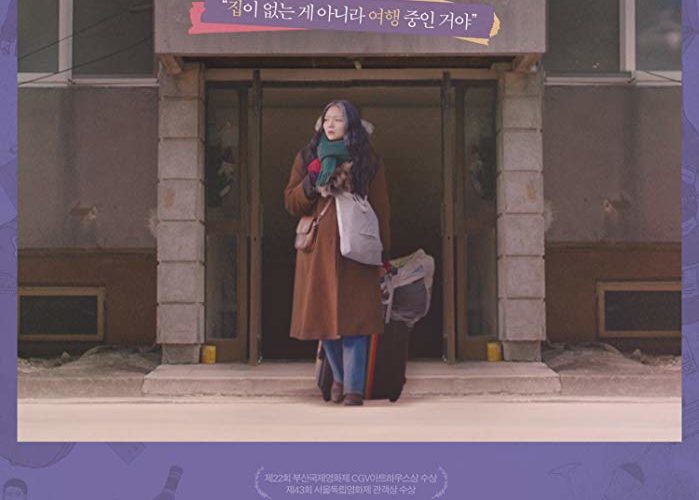

It’s not just the housing market, though, since inflation affects everything. Cigarettes increase in price too until Mi-So must make the hardest choice she’s ever faced: a roof over her head or the comforting escape of her vices. She of course chooses the latter and sets off on a reunion tour to see those old friends as a means towards shelter while saving up money for a deposit on a cheaper apartment. This young woman who many would say has her head stuck in the clouds is about to witness how the ones who embraced societal norms by growing up fared in comparison. Yes, they all have homes with room to spare (except Jin-ah Kang’s Moon-yeong, who covets her independence too much). But are any happier than she?

Suddenly our lazy assumptions are turned upside down as this seemingly “self-absorbed” woman with priorities askew proves anything but. Mi-so enters their homes to witness how their choices didn’t quite pan out. Moon-yeong is so career-driven that she’s taking glucose IVs at lunch to stay alert. Hyeon-jeong (Kim Kuk-hee) got married only to be taking care of three adults beside herself, the role of wife becoming her sole purpose despite ambitions long-since evaporated. Dae-yong (Lee Sung-wook) embraced the allure of material success only to find himself emotionally ravaged; Rok-yi (Choi Deok-moon) is stuck at home with an over-zealous mother praying a daughter-in-law will materialize out of the ether; and Jeong-mi (Kim Jae-hwa) can’t stifle a series of Freudian slips as far as her feelings towards motherhood are concerned.

Mi-so enters their domiciles with a clear ulterior motive — despite also genuinely wanting to catch-up — and finds out her unwitting disconnection from society may have saved her from an even worse depression than what’s left her to numb the noise with nicotine and alcohol. While she might be trapped within her inability to put down roots, they’re trapped inside lives wherein her nomadic existence only reminds them of the parts of themselves they threw away. Mi-so sees their sadness and can’t stop herself from doing everything in her power to help alleviate it, even if only for an hour. The one who’s seemingly desperate for shelter discovers that retaining her identity was most important after all. With it she can provide them what they had forgotten they needed.

So rather than use Microhabitat to open her protagonist’s eyes onto everything she lacks, Jeon exposes how non-conformity is just as viable a path towards contentment as the opposite. She draws Mi-so’s friends as slaves to a system that inevitably rules them with mortgages, families, and cookie-cutter goals. Jeon writes them in a way that allows them to mask their jealousy towards this unexpected houseguest with pity, equating their privilege with superiority despite the self-imposed prisons it erects. In their minds Mi-so is a loner living off the grid by herself without initiative when the truth is closer to the fact that they have pushed her away. Their insecurities and self-loathing have made it so this kind soul with infinite compassion towards them is more burden than saint.

The result is therefore a profound meditation on the myriad choices we make to build our lives. It reveals how struggles must be endured whether you pick inner happiness or outward success. The former ensures that you will lose people you hold dear as they succumb to the temptation of more while the latter potentially leaves you caught in an empty existence as a hollow shell of the vibrant soul you once were. Neither is perfect nor better than the other. It’s truly up to the individual to decide which path is for them. For Mi-so the simple life allows perspective free of pettiness. It supplies her an appreciation beyond social standing or economic solvency. Her actions aren’t dictated by external appearances; they’re pure and from the heart.

Esom is a bright and beautiful light shifting from one place to the next as though a guardian angel bringing joy and unbridled affection none of her friends have known for too long. She plays the broad moments of hijinks with superb comic timing (Rok-yi’s mother may actually try to prevent her from ever leaving again) and the softer, melancholic ones with deft emotional range. Whether it’s comforting Dae-yong from behind a closed door or providing empathy to an over-the-top client (Jo Soo-Hyang) hiding behind a carefully cultivated façade, Esom’s Mi-so gives everything to those around her. It’s no surprise then that she would neglect her own wellbeing in the process. But while cigarettes and whiskey aren’t healthy per se, they’re exactly what she needs to survive.

Microhabitat is now playing the Fantasia International Film Festival.