“I’m like everyone else,” writes about himself Cristiano (Aristides de Sousa), the working class hero at the center of Affonso Uchoa and João Dumans’ Araby, “It’s just my life that was a little bit different.” Calling that an understatement would be a euphemism. An average-sized and average-looking factory worker in the Southern Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, Cristiano is an everyman par excellence. Neither charismatic nor particularly striking – at least not on a first look – he seems so ordinary it takes us twenty minutes to understand he’s Araby’s protagonist, and not some flickering extra. When we first meet him, he is given a lift to his steel factory; up until then, Uchoa and Dumans had followed Andre (Murilo Caliari), a pensive and bookish teenage boy living with his aunt Márcia (Gláucia Vandeveld) in a derelict house close to the hellish steel mill. By the time we next hear about him, Cristiano has suffered an unseen work accident, and is stuck in a coma. Asked by Márcia to collect his belongings, Andre arrives at Cristiano’s place, and happens upon a spiral-bound notebook which the man has used to transcribe a decade’s worth of memories.

First hashed out as Andre’s story, from here on Araby becomes unmistakably Cristiano’s, as Uchoa and Dumans zero in on the several years the man spent meandering across Brazil trying to make ends meet by working any job imaginable. Jailed in his teens after stealing a car, Cristiano left prison with no money or place to go. Thus begins a quietly epic road trip of Wim Wenders-like proportions, if anything for the harsh reality and bleak prospects the young man faces in his struggle to stay alive. If “my life was a little bit different” sounded like an understatement, it is because, by the time Araby clocks its 98 minutes (a remarkable feat by editors Luiz Pretti and Rodrigo Lima, considering how much life is squeezed into them) there is hardly anything Cristiano hasn’t done. Once sprung, he lands a job at an orange farm; screwed over by a boss who gives him no pay, he lands a gig working at a highway construction site; after that ends too, he gets a job at a textile factory, and following further peregrinations – including a brief stint renovating a brothel – he finally gets hired at the steel mill.

More an episodic summary of a meandering life than a standard three-act plot, Araby is a film of quiet pleasures. Cristiano’s journey may well be paved with crimes, punishment, injustice, death and even love – a romance with a work supervisor (Renata Cabral) is possibly the closest the lad comes to experience happiness – but Uchoa and Dumans’ script does not need much action or dramatic incidents to let its protagonist’s nagging loneliness sink in. In fact, Cristiano’s angst feels most vivid during the several exchanges with other social outcasts he meets along the way – from fellow ex-cons who try (and fail) to find a new place in society, to co-workers who fight (to no avail) to vindicate their rights and dignity.

Interwoven with Cristiano’s struggle for survival is the story of a man’s class consciousness. As much as a road trip, Araby is also a Bildungsroman of sorts: a-coming-of-age which for Cristiano translates into a coming-to-terms with his place in the world – a journey of self-discovery the young man aptly introduces as “the story of how I stood up for myself.”

For a feature narrated almost entirely by Cristiano’s voice-over, the fact that his road trip feels so entrancing is nothing short of extraordinary. Uchoa and Dumans establish a fine balance between words and visuals; Leonardo Feliciano’s cinematography offers a few breathtaking vistas of rural Brazil and accentuates the de-humanizing character of factories by alternating a cold and dark palette; and Francisco César’s score makes room for an aptly chosen 1965 folk ballad by Jackson C. Frank, “Blues Run The Game.”

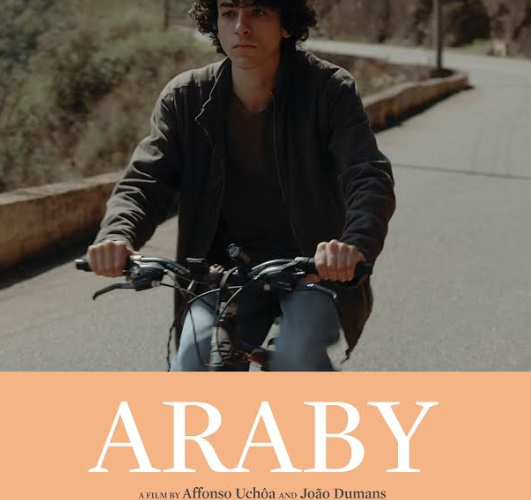

But it is de Sousa’s pitch-perfect performance that turns Araby into a memorable entry in its genre. Cristiano’s beguilingly ordinary appearance masks a multilayered, magnetic persona: a man who is at once cognizant of the marginal role society has assigned him, and fully aware his self-worth is not defined by it. And while Cristiano’s journal is discovered by Andre – who essentially sets the man’s story in motion – it is easy to forget Araby even features a meta-component: a few minutes into de Sousa’s narration, and the man’s soothing voice engulfs the audience into a timeless lesson in storytelling, conjuring up a piercing critique of workers’ exploitation cast in a lyric – and never preachy – tone.

Judiciously gritty in its specifics, Araby’s scope is ecumenical. Cristiano’s journey might be that of a fortyish un- (or under) employed Brazilian laborer, but the challenges he faces bestow a universal, Sisyphean quality. “It’s hard to choose something to tell,” Cristiano’s journal had begun. In a little over an hour and a half, Araby captures a whole world.

Araby is now playing at the Film Society of Lincoln Center and will expand in the coming weeks.