In Paul Thomas Anderson‘s The Master, Joaquin Phoenix plays one of the most unique alcoholics I’ve ever seen in a movie. What Aaron Johnson did to pot in Oliver Stone‘s Savages, Phoenix does here to liquid poison — and yes, I do quite literally mean poison. Paint thinner is but one of the sordid ingredients he uses to concoct his immediate-fix potions, which are usually created in some rusty, holed-up room, where everything he needs — dirty beakers, medicinal substances, forgotten flasks — are at his convenient disposal.

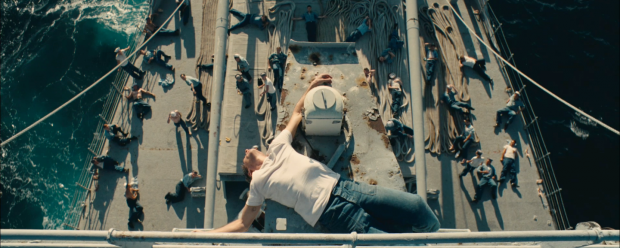

When we first meet Freddie Quell (Phoenix), in the midst of WWII, he’s in the naval service, and he has the behavior of an animal who has been kept in his cage for far too long. As Freddie’s oceanside compadres burn off steam by molding the damp sand into the figure of a woman with a generous bust, Freddie decides to take things a step further, straddling himself over the handmade beauty and thrusting his body with the hunger of someone who doesn’t want a woman so much as he barbarically needs one. (Freddie also pulls off the stunning stunt of being able to locate human genitalia within every Rorschach-test illustration he’s presented with.)

We see more of this caveman-like craving after Freddie leaves the service, and takes up a job as a photographer in a luxurious department store. Safe to say, the position doesn’t last long — if ever there was a man not meant for this job, Freddie is him — and his focus soon switches to manual labor. But his pattern of destructive boozing follows him everywhere, not only infecting his own body but those of the people around him. After one of his toxic libations drives a man to severe illness, Freddie has to go on the run, and it’s at this moment that he comes across a group partying aboard an extravagantly ritzy ship — a group led by the confident, mysterious Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman).

From here, a tough, muscular bond is formed between the two men. Though Lancaster may be a more successful societal figure than Freddie — he has no shortage of professional titles — he is, deep down, an off-kilter, somewhat twisted human being, and he recognizes that quality in Freddie as well. In one of the film’s best scenes, Lancaster interviews Freddie for the first time — an “informal” interview, Lancaster implores, while setting up a recorder and probably getting ready to take notes — and the resultant connection is hypnotic. Freddie likes the foreign, challenging nature of Lancaster’s inquiries, and if he’s not sure why he’s asked what he’s being asked, well, that doesn’t matter for a beast like Freddie. What matters, as we hear later, is that it “urges him toward existence.”

Amy Adams offers the most surprising contribution to the cast of characters, as Lancaster’s pregnant wife — she begins as a quietly endearing mother-figure and, in a single scene that represents both what’s absurdly right and absurdly wrong with The Master, suddenly transforms into a domineering, sharp-toothed matriarch. If the bulk of the movie is watching Hoffman and Phoenix go at it with one another — an enormous pleasure, as you may imagine — the fewer-in-number instances of Adams sparring with these men are equally exciting.

On paper, there should be a story to tell about the lensing, as The Master is the only Anderson feature to date not shot by Robert Elswit, who won an Oscar for There Will Be Blood. But stand-in Mihai Malaimare Jr., who’s mostly done work for Francis Ford Coppola, proves himself a threatening talent, favoring long, serene takes that inject us into Freddie’s hazy, screwed-up conscience. An oft-repeated technique, on a first viewing, appeared to be the tendency to keep the background militantly out of focus, and it’s a move that works well with the opaqueness of the narrative — as gloriously crisp as those 70mm visuals are, there are many sequences where we’re left in the dark about the precise location of a scene or where exactly it fits on the timeline of Freddie’s story.

It’s that aggressively enigmatic type of storytelling that makes The Master the most cryptic film Anderson has made yet. It’s often an electrifying move, removing us from scene-to-scene concerns that Freddie clearly gives no mind to, and powerfully distilling the volcanic emotion of the situations. But it is, too, a rather frustrating quality of the film. On too many occasions, the ins-and-outs of Lancaster’s delusional group feel aimlessly repetitive, and there are times throughout the movie when the process of trying to dig up the meaning of a scene or a conversation is so demanding that two possible conclusions come to mind — either there truly isn’t one at all, which I suppose would fit with the film’s chaotic agenda, or there is one, and we simply need some of Freddie’s moonshine to help unearth it.

Above all, I think, the movie’s power to arrest and unsettle comes from Phoenix — if you thought his I’m Still Here stunt called for some psychoanalysis, you won’t be changing your mind after this one, because I’m not sure there’s any way a completely sane person could possibly build a performance of such delusional, deranged commitment and precision. It’s a physical performance, more than anything else, Phoenix tweaking his joints and limbs so pungently that his Freddie almost comes to resemble a wild ostrich, his elbows always sticking out like sharpened knives.

And then there’s the face, with that creepy indent running from the nostrils to the top of the lips. As edited by Leslie Jones and Peter McNulty, the film always lingers on Phoenix for three or four seconds longer than a straighter film would, embracing his peculiar complexion. The Master ensures that we’ll never forget that face.

The Master hits theaters on September 14th.