The opening transition from credits to film of Petra Biondina Volpe’s Tribeca Film Festival Audience Award-winning The Divine Order is absolute perfection. With Jo Jo Benson and Peggy Scott-Adams’ “Soulshake” playing atop images from America spanning women’s liberation, civil rights, Woodstock, and more, we begin to see the impact of political revolutions changing the very fabric of first world societies. And then with a record scratch we’re transported to a rural village in Switzerland at the exact same time: the quiet patriarchal status quo of men at work and women at home intact with seemingly no end approaching. The nation was one of the last developed democracies to grant women voting rights with some districts holding out until 1990. Volpe has captured that tenacious struggle.

She does it by creating a sleepy town of rigid conservatives. Think about those red states in America that were targeted by Republican leadership as untapped and disgruntled voters who remembered the “good old days” of implicit oppression they’ve refused to adapt from. As an equivalent, Peter Freiburghaus’ Gottfried becomes your racist uncle or father wearing his MAGA hat while spewing rhetoric that for all intents and purposes speaks towards ethnic cleansing considering the only real thing that’s different from those “good old days” and now is his freedoms being extended to those outside his racial, religious, and gendered spheres. So when Gottfried tells his sons that “real men” would stop their women from seeking independence and forsaking God’s patriarchal will, he champions an archaic notion of supremacy.

The result is obvious: embarrassment. Werner (Nicholas Ofczarek) is bullied into becoming a farmer like he never wanted, his unhappiness spilling over onto the sheepish Theresa (Rachel Braunschweig) and their rebellious daughter Hanna (Ella Rumpf). Hans (Maximilian Simonischek) is younger and therefore not as susceptible to his father’s words, but his ambitions make him susceptible to those of the town for which he hopes to earn respect. So even though he is actually for women voting, he takes his employer (and leader of their local “against” committee) Dr. Charlotte Wipf’s (Therese Affolter) envelope for donations and refuses to let his wife (Marie Leuenberger’s Nora) go back to work (and lower their standard of living since clean houses and fancy home-cooked meals mean more than extra income).

Well, this is the last straw for Nora after ten years (estimated by her eldest son’s age) being docile and servile to the men in her household. She’s grown bored of her life and yearns to return to the happy days before marriage when she and Hans vacationed and treated each other equally without the responsibilities Swiss marriage law forced upon them. The reality that Hans could and would prevent her from working coupled by the heinous acts being done to Hanna by her parents for being sexually awakened open Nora’s eyes. It’s no longer about living comfortably once you’ve realized it’s impossible to think men in your country have women’s interests at heart. So with the help of some pamphlets, Nora fearlessly decides to take a stand.

But while the women in the nearby city have banded together to hold rallies and demonstrations, Nora is pretty much alone in her hometown — so much so that she might never have mustered the courage if not for the fact Hans was gone for a couple weeks during army reserves training. The solitude lets her take stock of what she has and what she wants, the fire that presents itself inspiring the older Vroni (Sibylle Brunner) to her cause. She had been the sole proponent for voting rights back in 1959 and thus knows how difficult it is to fight against a crude male populace and the silent women that don’t want to risk what they have now for something they may not receive in the end.

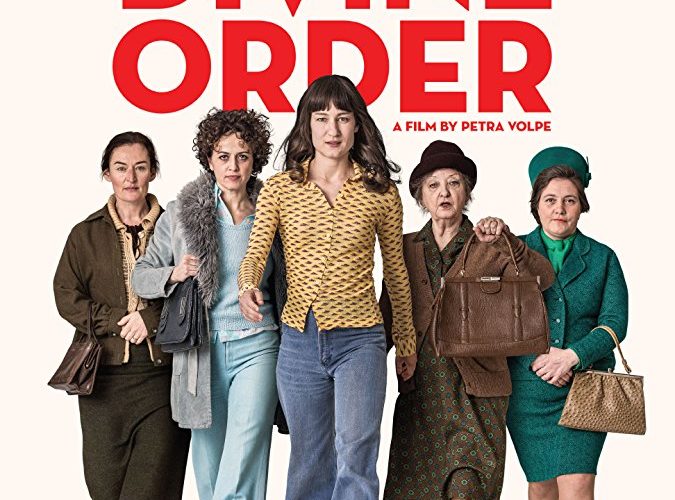

Nora, Vroni, and Italian restaurateur Graziella (Marta Zoffoli) band together to lead this rebellion — one that’s completely stacked against them. It’s not enough to win over the female population since it’s the men who are voting to give them what they desire. Education only goes so far when the oppressive norms of matrimony have been so ingrained in their everyday life. It’s a woman (Dr. Wipf) after all who provides their largest opposition, one that’s unmarried and the owner of a prosperous business. If she doesn’t want the vote — whether because she already has everything she needs or has always read the Bible in a way that prevents it — why would the men believe anyone else does? It’s a slippery slope made worse within an area steeped with tradition.

Volpe’s portrayal of this struggle is made better than most by how she translates the politics of their argument onto a relatable, human level. She’s not interested in the nationwide scope with vocal cities that everyone knows will vote one way or the other. This story — like the 2016 US election — hinges upon the forgotten communities on the fringes. It’s about their extreme reactions to any glimpse of modernity entering their borders. It’s about the importance of reputation and the intrinsic subservience that retains a good one in the eyes of leaders implicitly or explicitly consolidating power. And its unique perspective within a setting stuck in the past allows Volpe to make clear the intertwined relationship between women’s rights and the sexual revolution.

It’s not a coincidence that Nora is empowered after getting a new haircut and clothes. Nor is it that she’s emboldened by a recognition of the vagina as more than a birth canal. (A scene wherein a hippie teaches a room of women about “Yoni Power” is wonderfully authentic in its participants’ awkwardness and enthusiasm.) Add commentary on divorce, inheritance, domesticity, and the career versus motherhood argument and you’ll find that The Divine Order packs a lot into its brisk 96-minute runtime. But it never feels forced in the process. By setting her story in a small, close-knit town, Volpe allows the disparate yet equally important plights of Nora, Theresa, Hanna, Graziella, Vroni, and her daughter Magda (Bettina Stucky) to exist in such close proximity.

Her depiction of men is just as accurate in how many are cruel because they were bred to believe they could. The frustration of Nora’s children upon being forced to do chores (“But we’re boys.”) is subtle yet potent. The confusion within Hans when choosing between that which he believes and that which he must appear to believe to retain his community status proves a damning glimpse at cowardice’s ability to turn good men bad. It’s the same with women as many refuse to speak up in public despite doing so in private. That’s what makes those who do heroic. Calling out a blatant lie while fully cognizant of the potential consequences is the definition of integrity. The women Volpe researched and based her characters upon are heroes.

The Divine Order hits limited release on November 17.