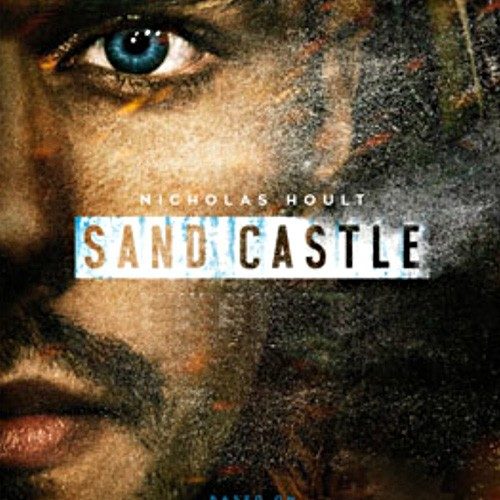

Similar to lead character PVT. Matt Ocre (Nicholas Hoult), screenwriter Chris Roessner joined the United States Army in July of 2001 to serve in the Reserves and earn college money. Two months later 9/11 changed everything. Suddenly he was thrust into a full-scale war in the Middle East and he needed to steel himself to that fact. He wasn’t in the Special Forces, Navy SEALs or Marines — he was just a soldier walking onto the frontlines like the rest. His story wasn’t one of unanimous heroics wherein he proved crucial to earning that “Mission Accomplished” banner everyone remembers as empty sentiment. Like so many military men and women, he entered Iraq at the beginning of something still unfinished today and left well before any true strides were made.

Roessner survived his stint and returned home with journals and photos depicting his experience. He took that money and enrolled in USC’s film school, putting pen to paper on what would become Sand Castle in his free time. He says it isn’t autobiographical — the main plot point of Ocre’s unit helping to guard and repair a destroyed water pumping station is completely fictitious — but it certainly gets to the heart of war’s futility nonetheless. He has channeled his emotions and memories into a tale that puts us in the action of a mission centered upon engaging a community too fearful to help even if they understood they should. His script isn’t about manufacturing distinct lines between good and bad as much as it is depicting the gray in-between.

This is what sets his and director Fernando Coimbra‘s film apart from the ever-growing list of war movies seen each year. It’s not about an infamous battle, heroic rescue, or superhuman icon that epitomized what it means to serve his/her country. Sand Castle looks beyond the action and instead focuses upon character and place. There’s the requisite cowboy looking to kill whoever gets in his way (Glen Powell‘s SGT. Chutsky), childhood friends who have each other’s backs (Neil Brown Jr.‘s CPL. Enzo and Beau Knapp‘s SGT. Burton), and compassionate leader (Logan Marshall-Green‘s SGT. Harper), but they complement the internal turmoil of Ocre. They’re the stereotypical soldiers who signed up to serve, who embrace the fear as it makes way into excitement. Like Ocre, however, they’re also regular guys.

What’s most intriguing is that Ocre is the “legacy.” He’s the guy — like Roessner — whose family served. So even if war wasn’t his reason, he signed up because it’s what was done. Rather than embody that rite of passage, however, we’re introduced to the Private slamming a Hummer’s door onto his hand in hopes of a discharge. It’s not bad enough to be sent home, but it is bad enough for him to be seen as the “coward” looking to escape. His unit and commanding officers (Tommy Flanagan‘s SGM. MacGregor and Sam Spruell‘s 1LT. Anthony) know it was intentional and as such watch him closely. Harper constantly asks, “How you feeling?” or “You up for this?” because he wants to give Ocre the opportunity to prove himself wrong.

Sand Castle does a good job showing exactly that. We see Ocre’s first time taking fire — his intelligence, observational skills, and uncertainty/fear as far as the horrific results of his actions go. We watch him wrestle with accepting the thankless mission of going on the ground with a Special Forces unit (led by Henry Cavill‘s CPT. Syverson) to fix the aforementioned pumping station—his desire to stand-by his own men weighing against the reality that his stomach might not be able to sustain anything more dangerous than his duties in the safer by comparison Green Zone. We watch him become the lone voice amongst dissenters to approach the Iraqi community and seek their assistance. And we watch the unavoidable nightmare forever waiting to consume him anyway.

He isn’t the only one afraid of that nightmare, though. Besides Chutsky — who really does believe himself immortal — they all have doubts. What separates them from Ocre is their understanding that they have no say otherwise. Signing on the dotted line made them property of the US Army and there’s no getting around it. They’ve found their reasons to follow orders and enter the hellfire. Burton loves the notion that his bullet has already been fired because it takes the pressure off as far as making a mistake. Enzo may not like where he’s told to go, but he’ll go because Burton is and Harper asked. And Harper himself is just pragmatic enough to be able to push aside the emotional chaos of yesterday and work towards tomorrow.

They’re complicated human beings doing what they do for the guy by their side as much as family and friends back home. But just as they are needed to do what needs to be done against a violent enemy, they need Ocre to be who he is too. The latter’s idealism is what keeps hope alive within an environment breeding cynicism. He and Harper engage a community leader in Kadeer (Navid Negahban) despite Syverson not believing their conversations will bear fruit. But while his reasoning comes from tactics and military hierarchy, Ocre’s comes from not yet relinquishing his humanity. By approaching someone with kindness and logic, that someone may return the favor. Whether it ends happily, however, isn’t up to them. Chaos remains chaos no matter good intentions.

So we begin to like these men — Ocre, Harper, Burton, Enzo, and Chutsky. We appreciate their necessity for caution as well as their capacity for compassion. We see a character like Kadeer sticking his neck out for what’s right above reality’s horror and understand that there was purpose in this war besides merely oil. As Syverson’s interpreter Mahmoud explains, though, civil unrest between Sunnis and Shiites occurred before and will continue long after. Everything the Americans are doing is basically a virtual Band-Aid. Men and women on both sides are dying for something that may not be possible beyond optimistic fantasy. But that is sadly their role. In this way Roessner hasn’t written an anti-war or pro-war film. Sand Castle merely shows the honesty of war’s infinite complexities.

That’s no small feat and ultimately vaults the movie above its conventions. It’s straightforward, misses the lofty emotional drama seen in Black Hawk Down or Saving Private Ryan, and is perhaps “slow” considering the number of firefights are few, but its authenticity is unquestionable. War isn’t always about defeating an enemy or freeing prisoners. Iraq and Afghanistan were always engagements that came with as many civilians praising America’s involvement as despising it. Deciphering which side each local you encountered aligned was therefore a fruitless exercise. That sense of helplessness is etched upon Hoult’s and Marshall-Green’s faces as their desire to help leads to betrayal just as betrayal leads to help. War has never been pretty, but the current lack of feasible finish lines has made it less so.

Sand Castle is now on Netflix.