Ricki and the Flash boasts one of the more curious cameos this summer, and it is not from some musician giving a guitar-rockin’ Meryl Streep a thumbs up. It’s Bill Irwin, who previously played one of the most heart-breaking paternal figures in director Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married, an acute snapshot into a family’s dysfunction as healed over a wedding weekend. Though Irwin stole the show in the Demme film that had a direct influence of the au naturale Dogme 95 movement, he’s here as someone who has to listen to a loud, vulgar bonding moment between actress Meryl Streep and her daughter, both on-screen and off (Mamie Gummer). The cameo is one of the few unexpected moments in the entire film — in fact, it’s not even a cameo if you’re not familiar with Demme’s last film, but it indicates very clearly what kind of project Ricki and the Flash is and isn’t going to be – a pronounced reflection of Demme’s previous version of dysfunction, and proudly a bit obnoxious with its sense of bringing people together. Nonetheless, it’s an underwhelming vacation from artistry from a very intriguing filmmaking trinity that includes Demme, writer Diablo Cody, and actress Meryl Streep.

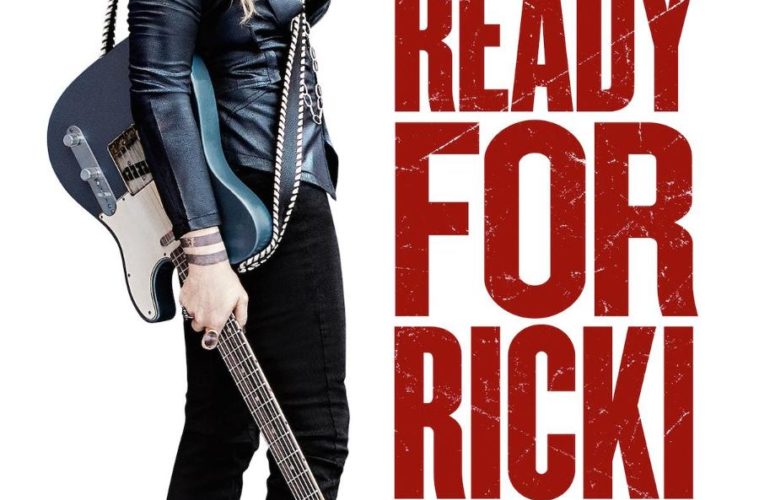

Streep plays a woman who lives a minor rock star life in perpetuity. By day, she is a cashier at the local Total Foods, by night she is the superstar of a small bar, playing the hits from Tom Petty’s “American Girl” to Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance.” She’s built a safe cycle for herself, including a string-less physical relationship with her guitarist Greg (Rick Springfield), that’s nonetheless broken when she gets a call from her ex-husband Pete (Kevin Kline). Their daughter Julie (Gummer) has just gone through a rollicking divorce, and Pete thinks that she needs her real mother, not just the woman who has filled Ricki’s void for many years (Audra MacDonald’s Maureen).

Ricki visits Pete and the rest of the Brummel family in their upper-class Indiana mansion, while Maureen is out of town taking care of her father. Through her stilted interactions with Julie, her sons Adam (Nick Westrate) and Joshua (Sebastian Stan) and his fiancee Emily (Hailey Gates), Ricki sees how her children have continued without her, and how her choice to pursue a rock ’n roll career have isolated her from basic human needs.

Streep is a redundant choice to play someone who is a rock star in their own mind and has a big presence to everyone else because of it, especially when the movie tries to treat Ricki as the outsider. The impression is a failed inverse on the bigness of how a multi-Oscar-winner fits inside a room of regular people. And while Ricki only has her stubbornness to complicate her arc, at the least she provides a few moments of sweetness, especially for someone who is so emotionally awkward. In the second act in particular, when she is dumbfounded by a selfless gesture from someone else, she has a great wordless expressiveness that completes the moment, however cheesy it might be.

More than Streep, Ricki and the Flash is a moment for two other supporting actresses, each with room to prove their cinematic guff, but only given limited space to do so here. The first is Audra MacDonald, who goes toe-to-toe with Streep with her own mythic quality as being the available mother that Ricki never was. MacDonald hits the potential showdown between the two mothers with a very striking calmness that alternates between openness and authority. Aside from showing the gratitude Maureen is owed by Ricki as a stepmother, their scene (one of Cody’s best here) opens up the very different life courses these two women have taken in motherly duties, and how they’ve either benefitted or worsened for it.

Of all beings within this dysfunctional tale, none are as raw as Gummer’s Julie, who thunders into the movie without a care for how she’s perceived, just as a person might be when they are entirely carved out by grief. Gummer treats this crucial part of the story with an unpredictable attitude and a defiant physical presence (her chaotic hair, sleepless eyes, and baggy clothes). Julie might fit better in a movie less tidy than Ricki and the Flash, but one can be grateful that she provides a raw spirit to it, especially in a representation of a complicated emotional state of mind.

The underdog, or at least as it may be reported, for the film is “Jesse’s Girl” singer Rick Springfield, who is most of all a surprise for the dramatic weight he’s given by the script. As a credit to Springfield’s on-screen charisma, he owns the cheesy moments with an unblinking sincerity.

Underneath the periodically pandering, feel-good nature of Ricki and the Flash are the autobiographical details. In context, Streep is playing a performer who at the very least isn’t always around her family, but specifically does so opposite her real-life daughter. Cody is herself a working woman and a mother. There’s also the most directly autobiographical detail that Cody’s mother-in-law has fronted a New Jersey bar band for years, of which Cody has often seen her play, and become fascinated by her life narrative.

Nonetheless, this motivating context doesn’t make the movie’s desires for puffy drama any more intriguing. When the film is clearly orchestrating its dysfunction, (setting a mini-reunion inside a bourgeois, crowded restaurant) or resolving its bigger conflicts with shamelessness neatness, the story can only boast a pandering feel-good nature. Even some fine domestic tension between characters gets an easy resolution, as if studio projects can only handle so much stress until they just fall back into harmony.

Ricki and the Flash does succeed with broadcasting a message, which it does in a typically loud (but not intellectually endearing) fashion. Within Ricki’s story is the idea of a woman who avoided domestic duties for her own dream, and it comes with a heavy-handed exchange between her and Kline (“Aren’t I allowed to have two?” she asks). Or, there’s the movie’s trailer-featured finale, which ends with a performance of Canned Heat’s “Let’s Work Together.” Curiously, everyone in the scene, “every boy, girl, woman and a man” seems to know the words. These are important sentiments, especially in what this movie does in showing how the definition of the nuclear family has changed in just a couple decades, but with flat charisma and orderly chaos, Ricki and the Flash proves to slack in the crowd-pleasing entertainment this exciting triumvirate is slumming for.

Ricki and the Flash opens on Friday, August 7th.