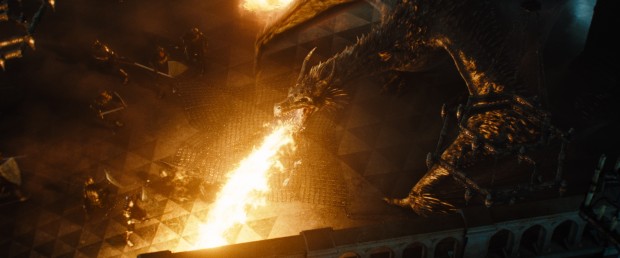

In the climactic final battle of Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, the imperious and delightfully wicked queen Maleficent squares off with plucky Prince Philip and informs him that if he wishes to save his princess, he’ll have to deal with her and “all the forces of Hell.” Then, she turns into a fire-breathing dragon. This is not a woman who messes around.

In fact, so unapologetically and nonchalantly evil was Maleficent in the 1959 animated feature, that she rose to the fearsome top of the Disney villain heap and has remained there ever since. In a film that mostly paints women as old, doting nursemaids or flouncy day-dreamers, Maleficent is the only female with any real agency or self-possession. Sure, she’s also so vindictive and unforgiving that she curses a young girl to death because she was slighted a party invitation, but you can’t argue with her style or assertiveness. She’s the film’s greatest character precisely because she refuses to be defined by motive or psychology.

Well, goodbye to all that because Linda Woolverton’s script for Disney’s new summer fantasy Maleficent is hell-bent on deconstructing the mistress of darkness and relentlessly exploring the pain and neglect that sent her on a quest of evil. If you haven’t completely tired of hastily constructed revisionist fantasies, then the initial hook of Maleficent might have you vaguely interested; the evil queen was once a majestic and care-free fairy guardian, with her own set of wild, feathered wings and a heedless sense of nurturing goodness.

As it turns out, a ruptured first love and intimate betrayal sent this sprite on a course that culminated in her arrival at young Aurora’s birthday party, filled with spite and cruel magic. The road to get there, and the twisted, winding path back from it turn out to be hardly worth the audience’s energy and effort. Robert Stromberg’s film is a muddy experience, both visually and thematically, although Angelina Jolie vibrates with a radiant camp intensity that demands a better, more confident movie.

Stromberg, a first-time director who spent years working as a visual effects artist on films like Avatar and Oz the Great and Powerful, is overwhelmed by the material and fails to draw any intensity or pathos from Woolverton’s uneven but ambitious script. All across the production there’s a curious confusion regarding tone. Disney’s got millions of dollars tied up in what’s being marketed as a PG-rated family film, and whose most crucial scene is a thinly veiled rape that leaves its victim cold, broken and bloodied the morning after. Yes, parents, there’s a harrowing sequence—strongly portrayed by Jolie as one of great emotional distress—that practically and visually feels like a violation, detailing the way Maleficent’s true love deceives her, slips her a drugged cocktail, and then severs her proud wings and takes them back to the king in exchange for the crown.

A better film might have found an elegant and poignant route to explore this betrayal, resting on the fantastical and mythological a bit more, but Stromberg plays it so on-the-nose that it capsizes the film’s spirit. It’s hard to reconcile watching a diminished Maleficent, the bloody ruts of her wings poking through her dress, walk past cheerfully smiling sprites and trolls cavorting amidst a digital landscape. Sharlto Copley, who plays Prince Stefan, the man who desecrated Maleficent’s body and broke her heart, is both miscast and wildly erratic. He’s a great actor who has an unfortunate job of playing a statistic rather than a flesh-and-blood person, and the love story that showed early promise becomes one more marker of a picture that’s gone darker than its surrounding parts warrant.

The rest of the film fares no better, as Jolie comes into her own visually as the Maleficent we remember, even as her character turns out to be a drastically different concoction. This version of the witch isn’t really a villain at all, but simply a scorned woman who allows one moment of vengeful bitterness toward the duplicitous Stefan to manifest itself as a curse on the new king’s first-born daughter. There are a few interesting ideas here, but they never go anywhere because the filmmakers never seems that interested in understanding the interior currents that drive Maleficent as a character, let alone a woman caught between the worlds of nature and man.

Once Aurora and the three fairy sprites from the original cartoon come into the picture, it becomes clear just how revisionist Woolverton’s script intends to be. Maleficent, now joined by her sarcastic shape-shifting crow Diaval (an amusing but wasted Sam Riley), watches over the young girl as the curse looms—one prick of the spinning wheel on her sixteenth birthday!—ever nearer. The fairies are a useless and irritating lot, and they don’t provide much care for Aurora, or relief for the film’s audience. Elle Fanning as the teen version of Sleeping Beauty is all sweetness and light and spark, but her role is so dramatically malnourished, that she fails to really connect with Jolie, which is where the second half’s narrative anchor lies; the relationship between Aurora and Maleficent.

Although one would expect an expensive film helmed by a special effects artist to at least look good, the visual layer of the picture may be its most disappointing. There’s no sense of a cohesive or thought-out world here, and the fairy-tale creatures look like they have been plucked from the doodled edges of an 80’s kid’s math homework. The script is consistently contradicting itself, and character motivation is so shifting that I often wondered if some scenes had even been edited together correctly. The fantasy world itself, marred further by hastily designed 3D, offers no respite from the murky intentions of the rest. There’s nothing here you haven’t seen before, done better, and the meager action scenes don’t rouse us to wonder or excitement.

To the extent that this is worth seeing—it’s a Netflix peek on a rainy day, at best—it’s because of Jolie, who has a great time playing this character and wearing her sexy comic-book costuming for all it’s worth. There’s such a flash of devilish glee in that one scene of villainy—the only one that’s very close to the cinematic source material—that it’s easy to wish the entire film had played in a more comedic or even satirical vein. Looking at Jolie and her stellar cheekbones and you can easily imagine the riches of a Mel Brooks, Terry Gilliam, or—gasp!—Baz Luhrmann’s Maleficent. What this film needs is someone behind the camera with a little character of their own.

Maleficent opens in wide release on Friday, May 30th.