Author Mary McCarthy (Janet McTeer) describes the titular Hannah Arendt (Barbara Sukowa) best when berating an emotionally blinded detractor vehemently slandering the German-Jewish philosopher in absentia in response to her reporting on the Adolf Eichmann trial in Jerusalem for The New Yorker. McCarthy dresses him down by saying his “being smarter” is easy while her courage is what sets her apart. No truer words are conjured while watching Margarethe von Trotta’s biographical depiction because Arendt’s internal struggle to reconcile feeling and understanding is visible at every turn. She and her husband Heinrich Blücher (Axel Milberg) spent time in French internment camp Gurs before escaping to America and thus know the horrors wrought by the Nazis. While such personal connection allowed so many to biasedly lust for revenge, she used it to look closer and seek answers.

As Blücher himself states, Eichmann’s trial in Israel was illegal. Mossad kidnapped the war criminal in Argentina and took him back to a nation that didn’t even exist at the time of the Holocaust. The trial was created as a venue for survivors to relieve their pain, point fingers, and seek retribution on the man admittedly responsible for placing Jewish prisoners onto the trains that would take them to their deaths. Adolf was no longer a man; he was the physical representation of a totalitarian regime needed to give its victims’ grief a face. It didn’t matter what he said behind the glass enclosure housing him in the courtroom or if he showed remorse. There was no way he’d survive the verdict and even Arendt is rightfully happy to know he would be hanged.

But it isn’t that simple. Of course she’d want to see Eichmann pay for his actions. Such desire doesn’t, however, excuse the situation surrounding his deeds and those of the people harmed. Rather than write about the facts everyone knew and assumed would come from the trial, Arendt writes about the philosophy behind man’s capacity to self-destruct. She coins the term “banality of evil” during the course of her reporting and openly suggests Eichmann was simply following orders. While it doesn’t excuse what he did, it does help us understand his lack of remorse. He took an oath to honor his superiors and did what they asked. Did he put prisoners on the trains? Yes. Did he kill them? No. In his mind another department did. What happened to them after leaving his care wasn’t his concern.

This is a controversial concept yet one Arendt couldn’t shake from being true. Her argument stemmed from acknowledging that no matter how sure anyone was of his complicity, no one could deny the discrepancy between the unspeakable horrors committed and the mediocrity of the man committing them. She begins to speak about man’s ability to stop being human, to stop thinking for himself and instead put all power into the hands of the corrupted. This becomes her over-arching revelation from the trial and ultimately her universal truth everyone needed to be filtered through. It was therefore only fair and honest to admit that certain leaders in the Jewish community were also responsible for not doing enough. And if people didn’t like her practical interpretation of Eichmann’s actions, they definitely didn’t enjoy hearing her blame the victims.

von Trotta and co-writer Pam Katz show how divisive Arendt’s words became by allowing us into her circle of friends. These are intellectuals from the past (Klaus Pohl’s Martin Heidegger with whom she had an affair at nineteen) and present (Ulrich Noethen’s old college peer and close friend Hans Jonas), a colleague and father figure within the German Zionist movement (Michael Degen’s Kurt Blumenfeld), and her confidants in McCarthy and assistant Lotte Köhler (Julia Jentsch). We watch everyone argue their disparate philosophical and political viewpoints before calming down and declaring their adoration of one another, thriving from the open forums and heated debates that only make them stronger and more assured in their beliefs. It’s amazing, though, how certain subjects can fracture these bonds beyond repair when those involved are simply too emotionally entwined.

If any of what Arendt’s detractors said was justified, it’s the vicious barbs about her not showing emotion. While on the surface her decisions and findings are made on a level of pure objective deduction, however, the filmmakers make sure to show such a mindset was directly attributable to her emotional wealth. The subject of her love and faith just wasn’t the same as others like her. Where they related to Judaism and its culture, she found connection to humanity as a whole. It wasn’t about what the Nazis did to the Jews, but instead what mankind did to itself. It may seem like a valid distinction now, but being a Jewish woman at that time speaking so openly about the failings of both sides couldn’t not be construed as insensitive, outrageous, and completely baseless.

Sukowa gives a memorably strong performance as her character traverses the many shifts of allegiance and compassion towards intellect and empathy. Hannah Arendt had the right to speak out because she was a part of the tragedy. But where she was able to detach actions and beliefs from the people themselves, those around her couldn’t do the same. This is why she could eventually reconnect with the man who taught her how to think (Heidegger) after knowing he joined the Nazis. It’s also why she wholeheartedly believed her relationships with Hans and Kurt wouldn’t be affected by her words. Some may have seen this thought process as naïve cowardice then, but now we know it as a brilliant mind fearlessly refusing to forget we all possess the capacity for evil whether maliciously or indifferently.

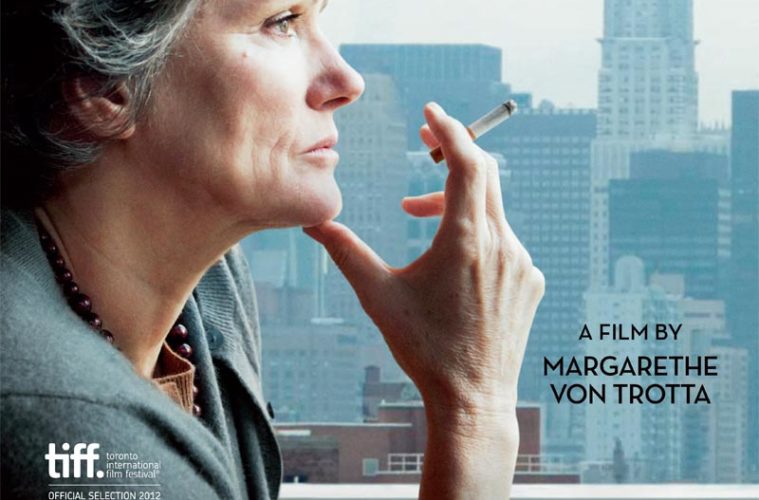

And while the heated arguments onscreen help prove how volatile a subject the Holocaust will always be; it’s an inspiring maneuver on behalf of von Trotta that drives Arendt’s philosophies home. Instead of casting an actor to play Adolf Eichmann the film uses actual archival footage so we may glimpse the same face Arendt’s stressful chain-smoker did in 1961. We hear the simplicity of his defense, the testimony of victims speaking about deaths devoid of any specific physical connection to the man on trial, and understand what Arendt meant. Eichmann’s face is that of a bureaucrat calmly describing the hierarchy of command and not one of a monster. His is of a voiceless man lacking the courage to do what’s right—a face not so different from many of our own.

Hannah Arendt opens in limited release today in NYC and June 7th in LA.