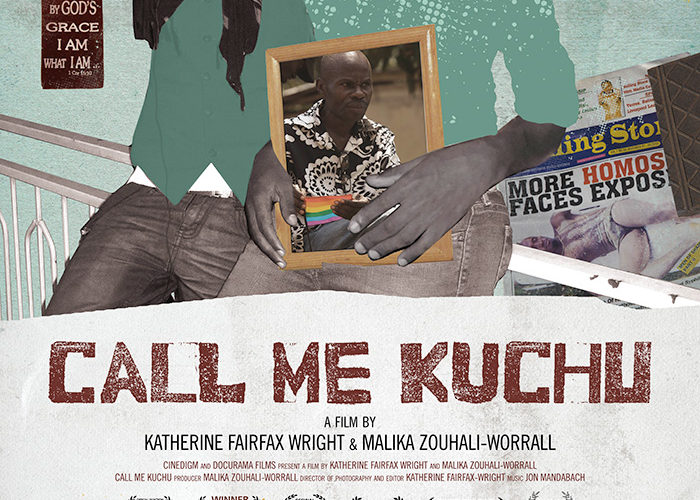

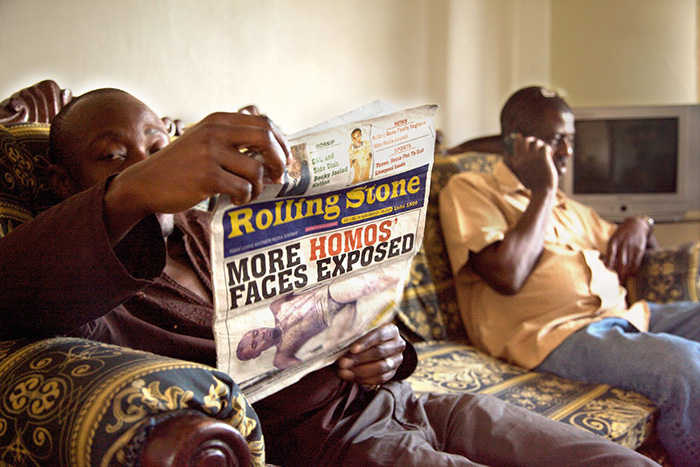

Created as a documentary to expose the horrifying human rights offenses committed by the Ugandan government against the LGBT community, directors Katherine Fairfax Wright and Malika Zouhali-Worrall were given impressive access to the nation’s most vocal activists by following them as the fight raged on the streets and in the courtroom. With local newspaper Rolling Stone outing as many homosexuals as it could in tasteless, tabloid-style photo spreads courtesy of paid infiltrators and a Christian zealot-led Parliament hoping to rapidly push through a new law declaring sexual orientation punishable by death, every brave soul standing against the tide risked rape, abuse, and death daily. And just as growing international support and a surprising local judicial turnaround appeared to earn the promise of victory, the risk became a tragic reality as threats escalated into murder.

Call Me Kuchu is a powerful look at how a nation’s ignorance can provide the basis to viciously persecute a people. With 84% of the population Christian, it’s easy to understand the inherent difficulty of living an openly LGBT lifestyle. For many of those showcased here, only close friends and family knew—and many still didn’t quite understand what it meant. To be out is to put a bull’s eye on your head and labels like immoral sodomist in your ears. Insensitive questions such as “are you doing it for money?” are thrown your direction while influential government officials call you monsters recruiting children onto your road to hell. When terrorist attacks like 2010’s bombing in Kampala during a World Cup screening are baselessly attributed to your community in the press, what is there to do?

This is the question David Kato asked himself and answered with a decision to fight. He became the face of the movement towards equality, going on television and testifying in court whenever necessary. Fully aware of what being openly gay in his home country meant, he willingly moved back from a six-month stay in South Africa to lead this liberation cause. His was a non-violent activism that spanned fearlessly celebrating his and his partner’s nine-year anniversary in a backyard party to hiring a lawyer to file an injunction against Rolling Stone managing editor Giles Muhame’s admitted disregard for the right to privacy. We’re given access to David’s frustration and anger at each new paper’s despicable headline rhetoric like “Hang Them” as well as the unwavering optimism that he would eventually see victory.

No matter how important Kato’s role and ultimate sacrifice, however, his isn’t the only story told despite most loglines for the film describing it as such. Any of the other activists on camera could have been victims of the same inexcusable tragedy and are thusly depicted with equal care and compassion. The filmmakers couldn’t have anticipated their film’s end, only that the pressure and fear would continue to escalate as the Parliament vote for the “Kill the Gays” bill approached. So while it was David’s death that finally swung the world’s attention, it wasn’t the only battle being fought. Women like Naome and Stosh, men like Longjones and Bishop Christopher Senyonjo all played their roles and deserve as much appreciation. David opened the door while they sought to continue ensuring outsiders couldn’t close it.

There are many uplifting moments of pure individuality standing against the persecution that will make you smile. Whether the opening anniversary, an impromptu 2010/2011 Miss Kuchu Pageant, or David’s undying love for his mother, the community did what they could to live the lives their government wanted to take away. We need these sequences of hopeful joy because the majority of the story is difficult to fathom as reality. If hearing how the bill requires parents to give up their homosexual children to the authorities isn’t enough to turn your stomach, Stosh’s nightmarish retelling of her rape at the hands of a man looking to “educate” her on heterosexuality will shatter your heart. And religiously fundamentalist Pastor Solomon Male still has the gall to ask where the proof of abuse and oppression is.

As a result, Call Me Kuchu is far from objective on paper even if we should consider it so when this kind of subjectivity can have no moral opposition. Men like Male and MP David Bahati—the bill’s main advocate—are justifiably portrayed as villains through nothing more than the words coming out of their mouths. Their arguments that homosexuality goes against Ugandan principles of procreation for family and clan ring utterly false as declarations that they love the LGBT community and merely want to save them hold no water with the solution being death. It’s therefore maddening to admit they aren’t even the worst evil portrayed. That unexaggerated honor goes to Giles Muhame, a devil whose abject disregard for the sanctity of life and uncontrollable laughter at his victims’ plight is disgusting.

I cannot believe anyone watching this documentary won’t become emotionally enraged at how cruel mankind still is in the twenty-first century. If it were proven that Fairfax Wright and Zouhali-Worrall manipulated us by excising scenes proving Muhame and Male possessed souls, I wouldn’t care. Even if such footage exists it would be impossible for those men to ever save face. They are the true monsters here and seeing them speak with satisfaction in their eyes after Kato’s murder is unforgivable. Above disdain for their atrocities, however, Call Me Kuchu is ultimately a work to honor the heroes who stood against them. It’s about David fighting in the courts, Stosh surviving to tell her truth, and Bishop Senyonjo ignoring the church’s stripping of his title to fight for all God’s children no matter what.

Call Me Kuchu opens NYC & LA in limited release Friday, June 14th.