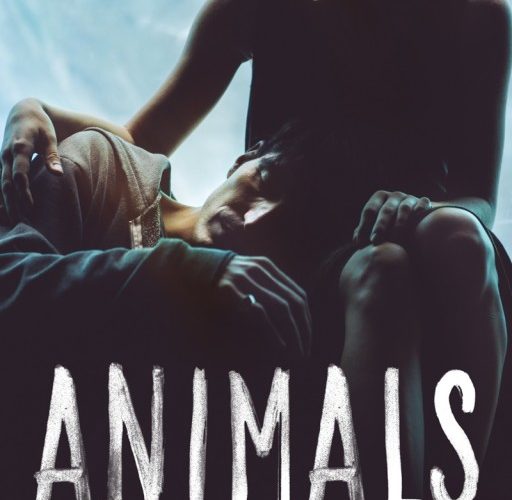

Jude (David Dastmalchian) and Bobbie (Kim Shaw) look like the well-bred, fresh-faced couple you’d find at the beginning of any indie rom-com. The only difference is that, in Collin Schiffli’s Animals, these two intensely devoted love-birds have a third, initially unseen partner that turns the proceedings into a doomed triangle: heroin. Avoiding most of the usual notes of drollness or self-importance that creep into many addiction-centered stories of addiction, Schiffli and his actors cut through the noise and deliver a modest but affecting portrait of two people standing united against the world, while it’s really their own inner deficiencies that tear them apart.

By showing his duo as two people deeply in love with each other and committed to standing united against all comers, Schiffli manages to buy some temporary escape from the impending sense of doom that often lingers over pictures involving drug addiction. Jude and Bobbie roam Chicago in a manner that, from the passing external glance, looks similar to any other couple; their appearances don’t initiate instant worry, and, as at the start, they look like typical youthful yuppies, sauntering around in a middle-class glaze. This is obviously a scam, one of many that the duo are involved in, each of them fixated on an unwavering goal of scoring more heroin and feeding the beast. They aren’t fixed atop the mountain, ready to fall — these two have long since crashed into their obsession and been gobbled-up long before the first frame of this film. We are watching them coexist at the very bottom, unaware that there’s always further to fall in this scenario.

What’s initially interesting about Schiffli’s film is the subtle way it chooses to observe the behaviors of Jude and Bobbie, ebb and flow of their relationship and their digressing sense of preservation, without constantly referencing the drug addiction. Of course heroin sits at the physical and ideological center of everything they do herein — until, of course, that fateful late-in-the-game moment where necessity dictate that something must give — but there’s no sense in belaboring it because this part of their life’s ritual is taken for granted. They engage in low-key cons (e.g. selling stolen CDs or having Bobbie pose as an escort) just long enough to grab the advance and then hightail it out of there. They have adjusted themselves to a place where they can even find a smug satisfaction in their ability to keep skimming off what they see as a greedy, lethargic society.

At one point Jude muses, “We couldn’t have been born into more ideal circumstances,” and Bobbie offers up, “Why does a bird keep flying into the same window?” Rarely do you see heroin addicts who have the agency or wiggle-room to be this pretentious about it. In the first half of Animals, this may be where Schiffli’s film struggles the most, finding some tangible holding ground between the romantic, enticing notions that originally entrapped Jude and Bobbie and the stark-faced reality of where they really are. There’s no denying that watching these two move from day to day, zigging and zagging to stay one step ahead of their fate is engrossing, and there’s a point where you’re rooting for them in the moment. So much of this is down to how the picture is made, and you’ve got to give Schiffli and his pair of actors credit for not charging in from the usual angles, but taking the time to get us into the headspace and identity of these characters before showing us the complete desolation of their situation.

Look at the use of color and sound, which moves in and out of different emotional and physical moods, winding through dreamy warmth to frenzied, jittering anxiety. Schiffli calibrates the imagery to match the interiors of his character’s secret spaces and starts to suggest that the thin membrane of protection they’ve built up against their current lifestyle has been all but dissolved by it. When the grifts become more clumsy and desperate, the dangers more immediate and apparent, we begin to witness a dual unraveling and restoration of these two and their relationship. Small but pivotal acts of kindness — one of them from a guard (John Heard) whose laptop they try to steal — have resonance and impact because they would not have been expected or accepted at the film’s start.

Animals ultimately travels the same well-worn path of all addiction films — it’s very hard not to, given the limited, fatalistic trajectory that governs the routines of a heroin addict — but it nevertheless finds a few fresh ways to get there, and it uses the gifts of Dastmalchian and Shaw to humanize and empathize the people living underneath the addiction. These are strong and sensitive (but not sentimental) portrayals, and given how harrowingly real his Jude seems, it’s not entirely surprising to learn that Dastmalchian himself spent five years as an addict.

The film is so grounded in just the right amount of gritty, honest detail that it feels a bit like a distraction when Schiffli feels the need to keep pounding away at the ‘animals’ metaphor by showing us the inhabitants of the Lincoln Park Zoo and comparing them to his couple. Everything one needs to know about the thin line between instinct and actualization that haunts these two is starkly encapsulated in a pivotal scene, where a strung-out and irrational Jude and Bobbie consider threatening a woman and her baby with a heroin needle. Sure, some of Animals meanders through those alleys we expect, yet it hits enough unexpected notes, both of damnation and redemption, that it stands above most of its contemporaries in the subgenre.

Animals is now playing in limited release and available through the film’s official website.