You can’t tell the story of Marie Curie’s genius without also touching upon the complex ramifications of the scientific work she accomplished. As her husband and research partner Pierre says in a dream at the tail-end of Marjane Satrapi’s cinematic adaptation of Lauren Redniss’ graphic novel Radioactive, “You can only throw the stone in the water, not control its ripples.” Her stone was the discovery of two new elements (polonium and radium) and the concept of radioactivity that so intrinsically connects them together. And while some of the resulting ripples that formed were game-changing advances in mankind’s evolutionary trajectory towards the future (nuclear energy and cancer treatments), others fed into our species’ lust for power and destruction (the atomic bomb). Both roads are crucially important to her legacy.

The reason is simple: you can’t have one without the other. Does the number of lives saved by Curie’s science outweigh the number of lives lost? Maybe. Maybe not. What the former doesn’t do, however, is erase the latter and neither should a comprehensive look at her life. Whether or not Jack Thorne’s script provides a comprehensive enough scope is definitely up for debate (there’s only so much you can do with these sorts of biopics considering how much information and motivation must be packed into a sub-two-hour runtime), but the question of cleansing it from the horrors that followed is not. Satrapi presents each glimpse of the carnage as prescient sequences playing out beneath speeches warning of their potential. Curie was never naïve to these inevitabilities.

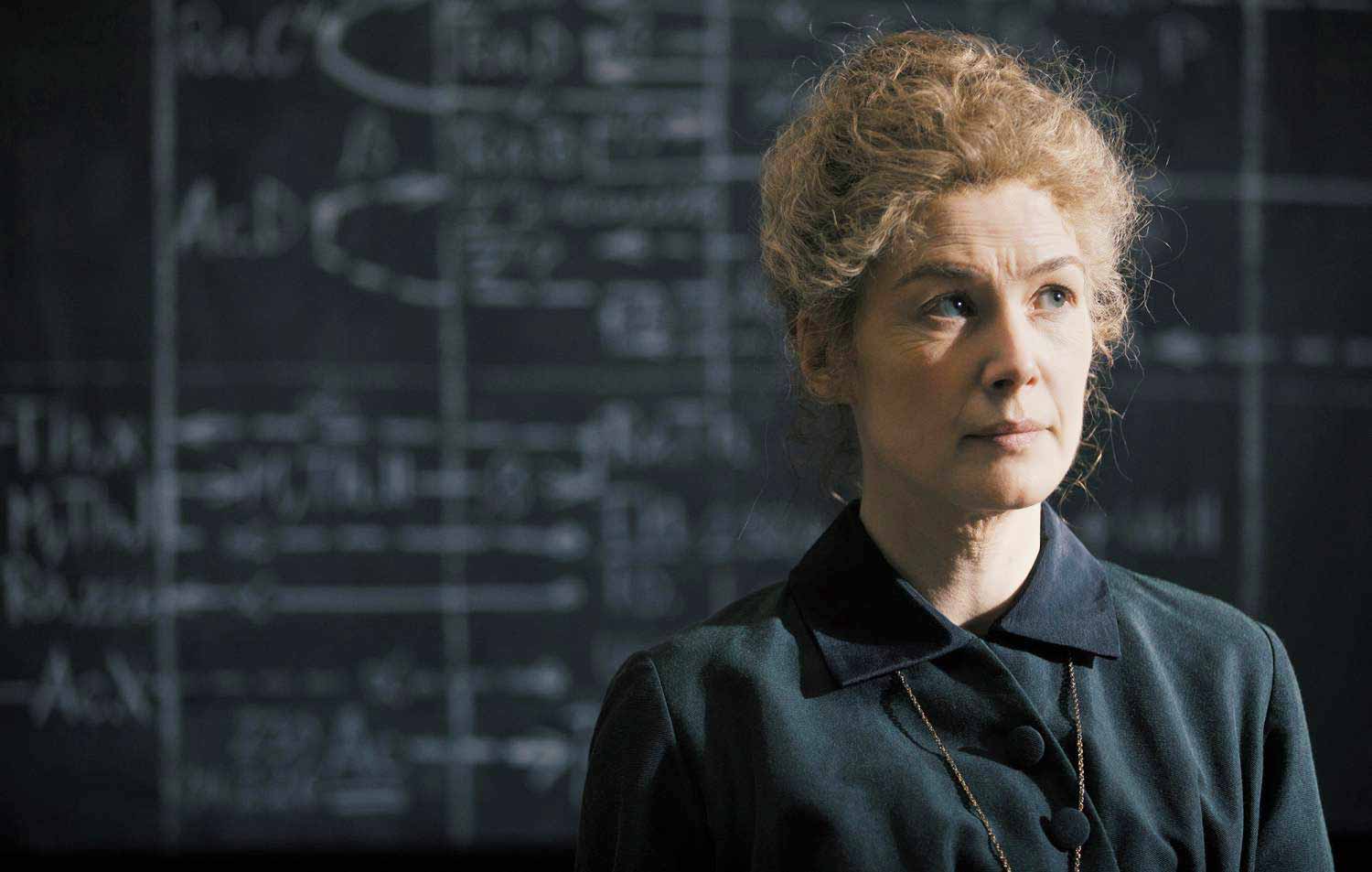

It’s no surprise to find that out after meeting this cinematic rendition of the famed physicist and chemist as portrayed by Rosamund Pike. Right from the start we see her headstrong independence, unwavering sense of self-worth, and tenacious drive where her work is concerned. From Maria Skłodowska’s inability to be bothered by a man in the street (Sam Riley’s Pierre Curie) showing shocked interest in her carrying a book on microbiology to a fierce defense of the respect she demanded, deserved, and wasn’t granted by her fellow researchers at the Sorbonne, it’s easy to see her pragmatic realism. It’s one thing to hope her work would lead only to humane applications and another to blindly believe that could be true. Complete control is an illusion.

Nothing proves this truth more than the hardships she faces throughout the film’s decades-spanning breadth (the majority of which is focused on her work with Pierre). Despite some strange dialogue that’s probably a byproduct of having a man adapt regardless of Satrapi still keeping it in the final cut (“The lack of funds and resources hindered me more than being a woman ever did”), gender was a huge struggle to overcome in nineteenth-century Paris. It was precisely because she was a woman that those funds and resources were lacking. Case and point: Pierre. The gatekeepers keeping her on the fringes kept him there too. He conversely had a lab, team, and budget to share. She had to fight just to get her name on her first Nobel.

There’s also the matter of public opinion that arose due to a later affair whose fallout was the publishing of intimate letters showing her “audacity” to speak frankly about sex. It’s no wonder that Satrapi was drawn to the material considering her debut Persepolis. She knows what it’s like to fight oppression, conservative ideals, and nationalism similar to what Curie faced when her adopted home turned on a dime from labeling her a heroine to denigrating her as a “filthy” foreigner who should return to Poland. All of this had to do with Marie being a woman no matter how much the men standing in her way would say it was her attitude—one they’d probably admire had she been a man. And yet her resolve never wavered.

The only time she stumbles at all is when thinking about her partner Pierre. Theirs was a symbiotic relationship that both are quick to say changed the course of their lives forever. They made each other better in the lab and at home, always challenging and always supportive in ways that you wouldn’t necessarily believe possible in that era. So there’s a justifiable hole when he dies (this is history, not spoilers). There’s a relatable period of uncertainty as she attempts to put the pieces of their joined existence back together alone. Because Radioactive doesn’t give the years after his death enough space to feel as authentic and meaningful as the Curies’ time together, we sense the script’s transition into checkpoint central as we progress to the end.

Satrapi’s more fantastical visual flourishes become obvious (seeing Pierre’s face everywhere) rather than profound. We have to move to the affair with Paul (Aneurin Barnard) to spark Parisian animosity. We need to have the animosity to ever so briefly gloss over the women’s movement. And we have to fast forward so Marie and Pierre’s daughter Irene (Anya Taylor-Joy) can be old enough to give her mother an opportunity at redemption. I would have liked that last bit to deal with the tragic possibilities of radiation more than the character’s fear of hospitals (the death of her mother when she was a young girl marked her as an atheist loner), but the emotional beats and Marie’s continued determination to not let the patriarchal establishment question her genius succeed nonetheless.

I would have also liked a few more wild choices from Satrapi too considering her work with animation (the shadow of Marie and Pierre’s romantic embrace flies into the sky as the moon explodes into an irradiated light that transforms into atoms) and absurdity (nothing of the weird and underrated The Voices comes through at all). She does what she can to give some life to Thorne’s rather staid screenplay, but even that can’t stop the film from risking its audience’s attention with by-the-numbers plotting. Pike and Riley do their part in helping to alleviate this unfortunate reality by giving everything they have as lead and support. These types of biopics do ultimately end up being more about showcasing their stars anyway. Satrapi almost made it more.

Radioactive arrives on Amazon Prime on July 24.