Gao Qunshu‘s Beijing Blues doesn’t want for interesting ingredients: the targets of the film’s police-officer protagonist are petty, low-level thieves and hustlers, which is a refreshing change from the next-level hysterics we often see in Hollywood’s crime-genre villains; Gao mounts the film with a documentary-like precision, taking in as many procedural and environmental details as the frame will allow; and the movie operates on a level of self-reflexivity, both in its casting and in its execution, that is often humorous and enlightening. The problem is that the balance between these elements is never correct—and, as a result, the movie doesn’t realize the potential of any of its individual assets.

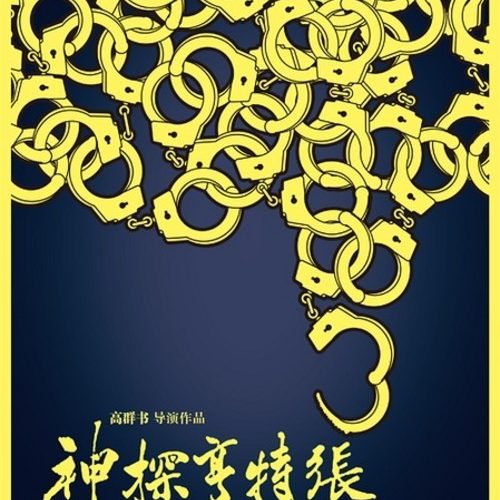

The movie’s Mandarin-language title directly translates to Detective Hunter Zhang, which manages to be both accurate and a little misleading. The main character is indeed a detective, and his name is Zhang Huiling (Zhang Lixian), but the connotations of the word “hunter” are way off: Zhang is more of a methodical, exacting tracker than a hungry predator. His approach to his job is determined by the criminals he’s assigned to catch: street-level swindlers whose operations are caught with Zhang’s ever-observant camcorder. It isn’t glamorous work—the crooks he catches like to accuse him of wasting his time with “little fish”—but Zhang is respected by his peers and his community, no doubt a result of his systematically decorated track record (he’s amassed over a thousand career arrests).

Some of the early sections of Beijing Blues—particularly the opening scene, which has Zhang fraternizing with friends and co-workers—plant the foundations of a character study. We learn that Zhang is plagued with asthma and diabetes, and there are moments throughout when he has to use his inhaler to survive the stress of a demanding foot-chase. Gao and cinematographer Wu Di use their camera to align us with Zhang, too: a confident early sequence in a hospital documents Zhang’s movements with long-take patience, tracing his every step up and down a staircase. There is also the matter of the (non-)actor playing the character, Zhang Lixian: a reputable journalist and microblogger, Zhang’s real-life image contributes significantly to the movie’s extensive representation of the media (at one point, a documentary crew even begins following the detective, with the intention of covering his work for a TV movie).

But the focus on the Zhang character is always seen within the context of the city at large. The movie regularly adopts Zhang’s point-of-view—frequently from inside his vehicle, where we see the action through the windshield and the windows—as he canvases the Beijing streets and sidewalks, stalking his suspects. This keeps us at a physical remove from the objects of Zhang’s interest: the behavior of the film’s criminals is usually witnessed from an extreme-long-shot distance, their faces and gestures obstructed by moving vehicles and passing-by pedestrians. Gao’s practical goal here is to embody the vantage-point of a surveillance unit, the members of which must stay out of sight until they’re absolutely certain they have all the evidence needed to make a successful arrest.

At times, this perspective works, especially when the criminals themselves are quirky. A clever development near the beginning of the film has Zhang breaking up an attempted robbery only to find out that the victim of the crime is himself a swindler with something of a family-crime organization. Another lively personality is a self-proclaimed psychic who solicits people on the street for money and personal relics in exchange for his seeing-into-the-future knowledge. More often than not, however, Gao’s handling of these sequences is uneven and perhaps misconceived: in accordance with the film’s documentary agenda, they’re often long and shapeless, which, at a certain point, dissolves our emotional and psychological relationship with Zhang. The details are nice, but if there’s no investment involved, there’s little apparent reason to continue watching after the second or third assignment is complete.

On top of this, Beijing Blues (as its title indicates) has interludes in which it strives to achieve a mood-piece resonance: folk-music montages are interspersed throughout the film, lending a kind of spiritual connectivity to Zhang’s various investigations (which become less and less temporally coherent over the course of the film). It’s a decent-enough conceit—but, like so much else in the film, the fourth instance of it is fairly indistinguishable from the first. There’s little sense of development or progress: more pronounced is the feeling that the film is simply spinning its wheels. Most effective, from an atmospheric standpoint, is the movie’s wintry setting: save for a striking composition set against some nighttime fireworks, Wu’s handheld lensing rarely has an expressive intent, but it gains natural substance from the frost in the freezing air.

When considered as part of a standalone vision, these clashing agendas are difficult to reconcile with one another—and it’s clear, by the end of Beijing Blues, that Gao didn’t find the ideal equilibrium between them all. The character-study angle begins promising (and the breaking-the-fourth-wall TV documentary even accounts for the actor’s best scene), but ends up lost in the shuffle. The bitter chill of Beijing in winter is initially tangible, but the music-driven intervals confuse the tone more than they expand it. The commitment to the procedural detail of Zhang’s work is similarly encouraging, but it subtracts from the other elements when the criminals lack intrigue, or when the action becomes increasingly challenging to follow. Had more thought and consideration gone into the net effect of these numerous perspectives, Beijing Blues might have lived up to its conceptual potential.

Beijing Blues will screen at Lincoln Center today. Details can be found here.