For a career as diverse, singular, and influential as Martin Scorsese’s, the task of summarizing it in even five hours is a mammoth task, making director Rebecca Miller and editor David Bartner’s Mr. Scorsese such a vital, impressive documentary. Across nearly 80 interviews, including 30 hours with Mr. Scorsese himself, Bartner weaves together the life tale of a fiercely driven filmmaker encumbered by studio demands, following his passions, regrets, and triumphs along the way. As entertaining as it is insightful, the five-part project is proof that every living director with such a career deserves such cinematic encapsulation.

With Mr. Scorsese now streaming on Apple TV, I spoke with David Bartner––on Scorsese’s 83rd birthday, no less––about the process of organizing such a massive filmography, what was left on the cutting-room floor, the experiments in editing during the process, capturing Scorsese’s film-preservation work, and the first Scorsese film he watched.

The Film Stage: Considering the breadth of Martin Scorsese’s filmography, I’m curious how you and your editing team worked on organizing the clips. Did you set by themes and subject matter?

David Bartner: Yeah, it was a super small team. It was an interview-based documentary, so we weren’t dealing with a thousand hours of vérité footage or anything like that. We had a lot of photos and a lot of archival materials, and then all his films. We probably had 70 or 80 interviews, including 30 hours with Scorsese himself, and so the way I always start things is by breaking everything down by theme. So first you watch all the interviews and you try to get what’s the emotional center, what’s the emotional heart, what is this person trying to tell us?

David Bartner

Then, beyond that, you break each interview down. I’d go through and I watch it, and I’m looking for emotion. And then also with a transcript, I’m highlighting anything that’s of interest. And then once I finish that, I go through all my highlights, and I give each highlight a theme, and everything can have multiple themes. So, one theme could be “Taxi Driver,” but then the second theme of it could be “Taxi Driver improv,” or “Taxi Driver relationship to De Niro.” So everybody’s going to have multiple themes.

I go through every interview like that, and then I take all my themes and I put them into bins. And then when I go to cut the next section about a film, I can open up Wolf of Wall Street, then I can see everything that every person has said about Wolf of Wall Street, and then I can see everything that every person has said about subsections of Wolf of Wall Street or ideas. Then not everything was about films. Sometimes it’s “Scorsese the man,” “Scorsese humor,” “sense of humor,” it can be “relationship to his mother”––all kinds of different things that we could put in. So that’s how I got started breaking everything down.

Then every character will have a bin with all their themes inside it. So when I’m cutting, if I want a certain person, I can see everything they had to say about each theme, which sometimes was important with Marty, where I feel I needed to hear from him. And sometimes, it might be a theme you weren’t expecting that suddenly fits in there, but I knew I needed his presence. And then he can come in with a big idea because I’m like, “Oh, yeah, that theme here actually really works in this section,” so it’s all about breaking everything down into these small moments thematically. Then I just have it at my fingertips because you can’t be creative until you’ve done that sort of front-end work. And I do all of that myself as an editor.

Wow. Speaking a bit more to the structure: Rebecca Miller has mentioned you didn’t land on it being a linear path right away. She mentioned you experimented with voiceover and even the point of view of his dog at one point. Can you talk about that journey of experimentation in the creative process?

There was always the idea that it would be linear a little bit, just because childhood was so important. There was this idea of grouping everything by theme. So violence would have a theme, religion would have a theme, women would have a theme, close-ups, long takes—we’d break everything up by theme. It ended up not working great because then you were kind of exhausted from his filmography after a certain theme. And then it also took his biographical story out of it. And then there was no satisfying way to do both, really, because if you did a whole chapter or a section or segment on violence at the end of Taxi Driver, and then you went into violent scenes in Casino and stuff, you’ve already exhausted a lot of Casino. We found that when we got there, we didn’t even want much to do with the film at all because we’d already seen it.

The voiceover thing, we ended up ditching it, but one of the challenges early on was: how do you tell this story without experts? Because we didn’t really use experts. So how are you getting through all the changes in Hollywood? How are you setting up this film and learning enough of what each film is about, so that you can then delve into the film without people feeling lost? And how do we do that without some talking head coming on camera and saying some stuff? There are good ways to do that with talking heads, but, for the most part, everybody interviewed is really personal to Marty and his story 98% of the time. So we did play around with having voiceover for a bit.

The idea was more Goodfellas-style voiceover, this character telling us the story. And then it was, “Well, who is this character?” And then we kind of had the joke that, “Oh, well, maybe this could be his dog,” because it’s a funny thing. It’s not in the final documentary, but he actually had a dog Zoë that never left his side through the ’80s. And then he had this Pomeranian or a small dog that he absolutely loved as a little kid that his grandmother had. Though he had asthma, he would love to hold the dog. Now today he has, like, five dogs running around all the time. So yeah: it was just kind of an idea that was thrown out there almost as a joke, but we didn’t try it.

There was another idea of being creative with voiceover. Since the documentary was so sprawling, a single voice wasn’t going to do it, and then it got to be the point where too much exposition actually got annoying. Then Marty was such a good narrator, but what’s interesting is that editorially, I did build a lot with voiceover—maybe the first half—and then I peeled it all the way and basically realized I could take it all away and everything pretty much still worked. So it kind of helped as a crutch for me because I’m a big “context is king” person. And so it was, in some ways, a fun way to write our way through the film. And then I realized once I had it there that I didn’t need it and I could still make things work. There was still a practical purpose to it that I found.

And it was fun because we got really playful structurally when you had the freedom of voiceover and that helped us get through point A to point D really fast, and then you realized, “Oh, well, we don’t even need all this stuff.” And so it really helped us move things along. It ended up being a decent exercise, even though I think we were definitely right to toss the idea.

Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker

Because you include so much, it’s interesting what’s omitted or a bit glossed-over. Miller has said talking about Hugo didn’t really work in the section for that time of his life, so it’s not included. You touched on some documentary work, but not all. From an editing point of view, how did you make those tough decisions? I assume there’s a ton on the cutting-room floor.

Yeah, there’s so much on the cutting-room floor. You have to make these decisions for the greater good of the series and keep both a chain of causality and also make sure everything ties back to all the work, to his life, in a satisfying way. There are great stories from his childhood—a ton of great stuff. It’s really horrible, but there’s a great story when Marty was a little kid and he witnessed a small child falling from a balcony and dying on the street. He told it in this really dramatic way, and it was incredible. We had it in for a while, but ultimately it didn’t work; it was tying everything else down. I think it had thematic purposes, too, which is: this is a kid who saw some serious stuff. He was living in a dense urban environment in the 1950s, and it wasn’t just gangs and the mob. It was just what life was like back then and what he saw. And there was another one: how he used to have to go down to the chicken shop for his grandma to pick up the chickens and he would see the butcher chop off a live chicken’s head and defeather it and stick it in the pot and all that. And he was really impacted. He was terrified of the whole experience.

There’s another great one about him getting his tonsils taken out as a kid and his parents told him that he was going to a circus or something, and he didn’t talk to his parents for a week after. We had a whole thing about tying it to the theme of trust in his films, because we had his parents talking about it in archival interviews, saying, “He brought it up 20 years later to us.” It was very funny. But how big a deal do we want to make out of these tonsils? It was holding everything else up. It just didn’t work in the structure. We had to sacrifice it for the greater good. His cameos, notably Taxi Driver—maybe it ultimately wasn’t as interesting as you think it could be, but that’s a huge scene. Everybody knows that scene. But that’s not in.

I really liked Nick Pileggi talking about that scene in Goodfellas where they’re going through and all the characters are introducing themselves to the camera, breaking the fourth wall. Nick is talking about how Ellen Lewis brought him and Marty to Rao’s, and he met all these characters, and it’s kind of based on that. We even had archival footage of Marty in the mixing room when that scene was going on. It was great, but we couldn’t do it. With Hugo, it’s obviously the film you could tie back to his life in important ways, but how to get from point A to point B to point C, and is it satisfying in the middle? We just had to make the call, and we had a really nice handoff with Shutter Island into Wolf of Wall Street.

Hugo is an amazing, amazing film, and it’s been interesting to see how much love that film gets from his fans after our thing has come out. Yeah, it’s just: we had to do it. In my head as an editor, I’m not always just thinking about who the fanboy is at home watching this. I’m thinking about who the person is who happens to turn this on and doesn’t know who Marty is, and how we can make the absolute most entertaining, deepest documentary that can feel close to them, as opposed to making sure we check off every box? It was always in my head as an editor. And I think Rebecca as well. I was always thinking, “If my dad watched this, knowing nothing about Marty, would he get into him?”

Speaking to the 30 hours of interview footage with Scorsese, do you know if he prepped at all for his interview by rewatching films? His references to specific shots and edits is remarkable, considering the breadth of his career.

I don’t know the answer to that. I don’t think so. It was really about him and Rebecca developing a relationship over time. I think he didn’t really know what Rebecca wanted to get into and why. I don’t think there were discussions of “Hey, I wanted to talk about this. Please watch it and revisit this stuff.” It was spontaneous. I do think that in the first interviews, he came up with photos of his family, photos of his childhood friends, and his drawings. He really wanted to talk about his early life, and so he came with some of that stuff. And then in the movie, you can see when he tells that story about George K. Arthur, he says, “I was thinking about this in the car ride up.” So I think there was some of that.

And then, late in the process, he had a revelation that Bicycle Thieves, he felt maybe it hit him, seeing the ending, because it reminded him of seeing his father’s humiliation from Corona, Queens. And he actually thought about that and wanted to get that recorded. So there were a couple of little things like that, but for the most part: no, I don’t think he was going through his drawings or anything. He’s also super busy. He’s trying to make his next movie all the time.

I love the cliffhangers you use at the end of each episode. Can you talk about crafting those specific teases?

They were fun. We didn’t know what we were making. We just had a big, long film, and then it was like, “Okay, we split it into episodes.” And then Apple was kind of like, “Well, you need things at the end of each episode to make people want to watch the next one.” [Laughs] I’d say that was kind of a requirement when we were making a series. And I was like, “Oh, man, we’re kind of fucked because all of this stuff is not like true crime.” Rebecca had the idea [of the cliffhangers]. It was a balance because we wanted each episode to have an arc in it. So it wasn’t like, “Hey, well, this will be a good cliffhanger, so let’s stop the episode here.” It was much more like, “We think this would be a good off point in his life.” Each ending has a combo of: there is a big transition coming up in his life, so I think people are interested because a big part of the story is about to unfold next, and then each one has its small tease, which is like, “Hey, something exciting is very much about to happen. Please stay.”

So it was navigating those two different levels, the macro and the micro—thinking about completing an arc, making sure that people are excited about what the next arc is going to be, and then these little moments. The De Niro one, we always had that cut like that, in a sense, being like, “Hey, I know this guy, you know this?” That was in. It just resolved when it was together. But then it was, “Oh, this is kind of a fun scene, so we can just like fully build out a tease.” The second one, “and then I collapsed,” that happened naturally. Episode three into four was the hardest one because there was talk about, “Well, do we wrap up Last Temptation of Christ and then tease out Goodfellas? And get people excited for Goodfellas?” That felt a little too, like, maybe film people would be excited about that… then Leo, we wanted to mirror with [De Niro]. So the Leo one came from that. That’s kind of how we did it. Instead of completing the scene, you’re just sort of cutting the scene in half and letting it hang, then leaving it to hang. It was tricky because there’s no big tease, like murder-mystery type stuff.

Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese

As a viewer, looking at this film and De Palma, they feel like extremely historically important documentaries, in the sense that you are capturing an iconic director’s filmography in his own words during the late stages of a career. It feels like every major living director should be asked to a do a documentary like this. As an editor, did that sense of importance ever hit you—that you’re creating what will likely be the definitive film portrait of a director?

There should be a lot. Maybe there’ll be more done. There’s the whole Cinéma, de notre temps series, which is awesome. And there’s a rich history of documentaries about filmmakers. It would be cool to get that updated, because there’s such exciting stuff happening in documentary. Sitting down with these people is really important, especially since we’re about to lose… I mean, hopefully not for another while, but there’s a great generation of filmmakers who are still alive. “Do they have another decade left” is a major question. It will forever be considered a golden age of cinema, and people will be watching those movies forever.

Did it hit me? I felt like that, luckily, is Rebecca’s job more. As the editor, it’s more my job to tell the best story with the material we have. I try to be more of a grounding attitude, because I don’t think it’s going to help me edit the film to feel that. So I try to ignore that part of it. I remember cutting King of Comedy and I was like, “I just can’t believe I get to work on this and be part of telling this story.” There were a lot of moments like that.

You use split-screen a lot in the film, so much so that it could feel like editing two documentaries at once. Where did that idea come from?

That was Rebecca’s idea. I’d say it was much more liberating than difficult because it was just a way to be playful. We did a lot of stuff like that, freeze frames. We played around the way you might see in It’s Not Just You, Murray! There was a version of the film that went that way stylistically, which is playing around with these New Wave techniques. That was hard to do with Scorsese’s work because he’s kind of an all-of-the-above kind of director. You can sort of do everything. So making our thing super-stylized in one particular type of grammar that he’s done didn’t ultimately serve his work, but the split-screen thing did, and it was just really fun. I didn’t find it a challenge. I loved that Rebecca had that idea.

It’s interesting to hear the moments where Scorsese is more reflective and may admit to regrets or shortcomings of certain films. For Cape Fear, it’s one of his few films he mentioned not loving all of it, and I didn’t fully realize how much The King of Comedy was more of an assignment on De Niro and the studio’s part than something Scorsese really wanted to make. Then his children mentioning how he was absent for certain stretches of their lives. You don’t want this to be a hagiography where everything just seems great and it’s important for a full portrait. How important was it for you to weave in these moments? Was there any left on the cutting-room floor?

No, I think we basically used everything like that for the most part. I mean, we didn’t use everything he said about every film. I think he does like King of Comedy. It is interesting; he was kind of nudged into it by De Niro and then kind of lost his way. Anything like that that Rebecca got or I watched, we would try to put in. That’s gold. I don’t even necessarily think it’s in contradiction to him being such a positive consumer of films. It’s more that he was showing some vulnerabilities to Rebecca. He definitely always makes sure to be like, “The actors did a good job.” I think he’s proud of it, but I don’t know—he’d have to say for himself. I never got the impression, watching the footage, that he ever was truly disappointed. It was more: if he showed any shades of vulnerability towards any of the films, we would make sure to put that in.

You see it in Color of Money, too. He talks about seeing Roger Ebert’s review. There was some talk about, “Should we keep this in?” Because you get into that trap of, “Okay, the film’s done,” and then we go to the reviews of the film, which we tried to avoid. We don’t do it every time. We try to only put it in when it’s important to him. But it was actually interesting because he’s engaging. He felt like he was on top again with Color of Money then he sees this critic who [had criticisms]. That’s another thing we left out, is: Ebert was a huge champion of Who’s That Knocking at My Door. But that whole storyline is complicated because it took him three years to make. But this felt important to put in because he’s reacting to a critic. You actually don’t really get to see filmmakers do that much anymore. Anything like that, we definitely put in.

Anything about family, that’s what we were kind of going for. I’ll have a sentence whenever I edit a film or an idea that tries to drive me to not get lost a little bit, and this one was “an uncompromising artist on a spiritual quest.” So anything that intertwined with that, I used.

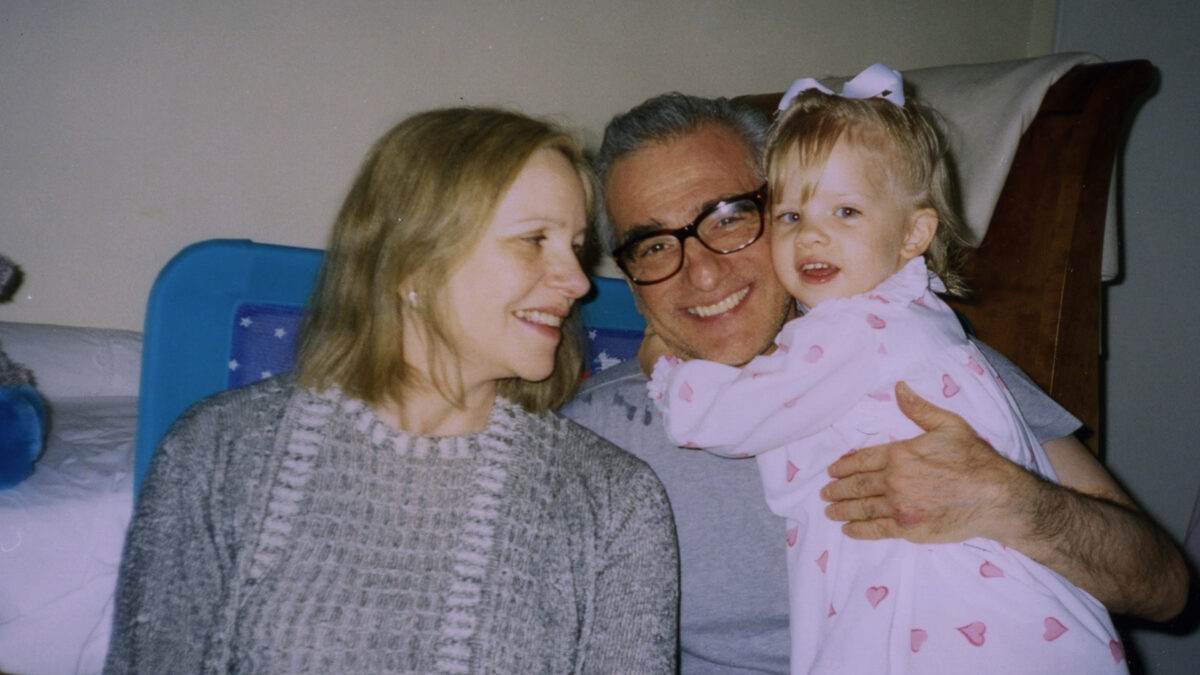

Helen Morris, Martin Scorsese, and Francesca Scorsese

I love that. It definitely comes through. I also love how much you spend on even Silence or films that might not have been wholly, fully embraced by everyone. It wasn’t his biggest box office, but it was an extremely important film for him to make.

That’s an example: we didn’t do the box-office reception of Silence. We didn’t do the reviews of Silence because at that point in his life, it didn’t matter. With King of Comedy, it mattered. He was talking about it. And with Silence, he matured as person—that’s the sense I got from the interviews. It wasn’t important that Silence didn’t bring in a lot at the box office. That wasn’t important to our story and him. Leaving it out reveals that.

It was great how you touched on everything he’s doing with the Film Foundation. Considering how influenced he was by certain films, this documentary could have been more about shot comparisons to classic cinema he was influenced by. I’m glad you kept it more focused on his life and career. Was there ever pressure to do more of that?

Yes, that was hanging over us a little bit. It’s one of those things where then you’re doing it all the time, and: when do you do it, and when do you not do it? He already has A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies and My Voyage to Italy. We do tell the story of Voyage to Italy that he puts in the beginning, but we do it very differently. He has told this story so many times, and other people have too. And it’s such a thing, like whatever Instagram reel showing the Scorsese shots. Some of that’s satisfying. I think it’s Margaret Bodde [executive director of the Film Foundation], who has the theory: Bob Dylan has the Great American Songbook; Scorsese has early cinema.

The direction we went more with it is the personal element of Scorsese. That stuff wasn’t related to the heart of our story. And it’s been done so many times, and if you do it sometimes and not others, why are you doing it here and not there? This isn’t going to be a trivia film. We do it with Psycho because he talks about it. That’s the other thing: when does he talk about it? Because it’s probably important when he decided to talk about it. And it’s not like Rebecca didn’t ask him. So what he talked about was driven by that, and we didn’t do a lot of critics who are going to talk about the thing. So, that sort of stuff didn’t make it.

His whole thing with Marvel—that’s related too. That’s not in there. That’s its own thing. The Film Foundation as well is incredible. I mean, he started that in the early ‘90s. It really was a separate type of film unto itself. You asked what was on the cutting-room floor. We had an amazing section about Michael Powell and then it ultimately didn’t work for people. We loved it, but it just didn’t work. It didn’t serve the full film, and so it didn’t make it.

Lastly: what’s your earliest memories of watching a Scorsese film, and are there any you changed your opinion on while working on the film?

Taxi Driver was my first Scorsese film. I got it on VHS at my local library when I was 15 years old. [Laughs] I remember loving it, but now I think it just went totally over my head, honestly. I think I just liked it because it was different and I was young I reacted to it emotionally. I liked the movie, but I think I was really struck by the ending and some of the political rally scenes. Then I watched it again many times and got it more, but I’d actually say that film hits me more afterwards. I mean, every one of his films now I see differently, but actually Taxi Driver, this narrative developed around it, or just maybe in my head. It was kind of just a “man movie.” And sort of maybe misogynistic.

I actually think that first half, especially—that idea of humiliation and feeling embarrassed for somebody—and you see Travis’s humiliation, and when Scorsese pans down to the empty hallway when he’s on the phone. That whole sequence with Cybill Shepherd is just… it is a horrible thing to be humiliated. And you don’t see it much on screen, just a character getting absolutely humiliated. When they’re walking, I think I was always so confused about that scene in the porno theater. I see it a lot differently after spending more time with it now, his ability to get us to empathize with this character.

And then New York, New York—I love that film now. It’s one that I hadn’t spent much time with before making this, and it might be one of my favorite Scorsese films. The musical sequences are just incredible. I like everything that he was trying to do. I love things when artists just take such a risk, even if they don’t fully pull it off. I’m fully convinced the four-hour version is absolutely brilliant. And we’ll never, never know. I love that, when somebody completely goes for it.

Mr. Scorsese is now on Apple TV.