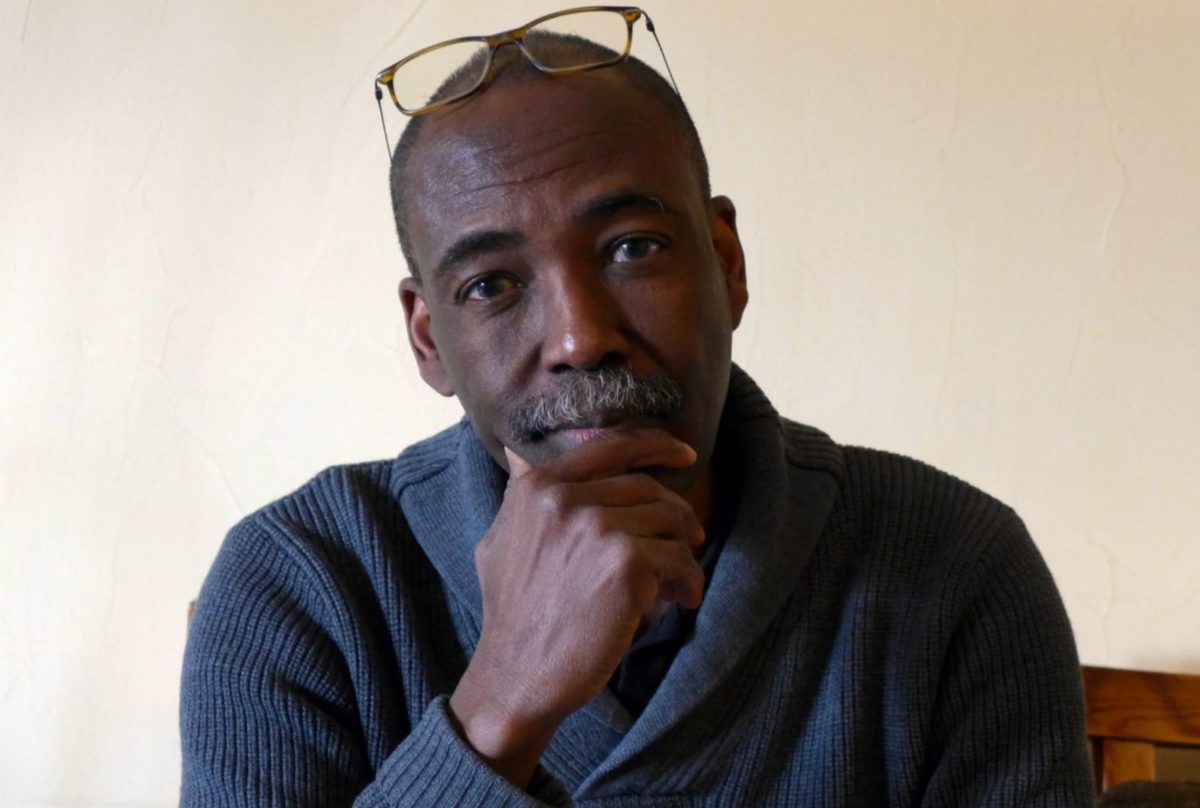

The Chad-born, France-based Mahamat-Saleh Haroun debuted his latest drama, Lingui, The Sacred Bonds, in competition at the Cannes Film Festival last summer. A formally classical vision, his morality tale follows a mother and her pregnant daughter as they navigate their next steps in Chad, a country where abortion is both illegal and condemned by religion. With Lingui now opening in theaters this Friday, courtesy of MUBI, I spoke with Haroun about seven influential films, from silent classics to international landmarks.

As David Katz said in his Cannes review of Lingui, “In Chad, whose two main languages are Arabic and French, “lingui” is a distinct term meaning a ‘bond or connection’; the film’s alternate title gives it a more pious hue—the ‘sacred bonds.’ But what’s fascinating and most novel about African cinema great Mahamat-Saleh Haroun’s new drama is the lack of an overtly religiose aura: the bonds created by its generation-spanning units of women are uplifting and resilient, while sought independently from Chad’s ruling, patriarchal class. To compare with conditions in the West, an analog would be to radical women’s networks, or even experiments in collective living and solidarity like communes.”

Read Haroun’s selections below, as told to me and edited for clarity.

Three silent classics: F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans and The Last Laugh; The Kid (Charlie Chaplin)

For Murnau, visually, it’s a kind of new thinking. He brings something very new, and even now when you see the films they feel like they’ve been made yesterday. So there is a kind of modernity that I love very much and the idea of not telling the story, but showing, which is very important for me. So I need less dialogue and that’s what I’m trying to do in all my films. And getting to place of [pure] emotions, as in The Kid, talking about people on the margins. This kind of mise-en-scène is really very important to me. So these are the three films, silent movies I love very much.

The Last Laugh: you can find it in A Screaming Man, which is also a situation of man who is fired and he’s in a hotel, so it’s a little bit different, but [Murnau’s] film is a reminder. You have this darkness, you have it in your memory so you put it there, but sometimes it’s not reflected. It can just come because it’s part of your memory.

When you see Charlie Chaplin he has sons or daughters. For me, Jim Jarmusch and Wim Wenders, they [capture] characters looking for something, and for me they all belong to the same family. I feel very close to this kind of cinema.

The Searchers (John Ford) and Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa)

I grew up with Bollywood movies and American western movies, so the influence is really John Ford. The Searchers, for me, is related to Seven Samurai also because it’s the same type of mise-en-scène, of composition––light and darkness––all these things are very important. And also, in the editing, there is something in John Ford, which is very important to me. It’s an acceleration and deceleration. We find that in Seven Samurai and Akira Kurosawa’s work as well. With The Searchers and Seven Samurai, one can feel that these films are kind of a piece of music. The Searchers is chamber music and Seven Samurai is a symphony for me. Also, when it comes to Ford and Kurosawa, you don’t only tell a psychological story, but you have a character who has a challenge and then he moves on to find a solution.

Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini)

Neo-realism is also very important to me. Rome, Open City, I saw this movie as a teenager and for the first time I understood that there is someone [like this] who is writing and is putting the camera somewhere. The writing and all the locations—it’s just like real life. You combine documentary, non-professional actors, professional actors, and you are trying to catch the real truth. So this is also very important to me.

Pickpocket (Robert Bresson)

Pickpocket by Bresson is very important for me also. It has this simplicity of telling the story with details. Just showing a hand, etc., but you understand the whole story by small details. It’s very simple and edited in an elliptical way. This is what I’m trying to do.

I [also] work with non-professional actors so I try to put them in the center of themselves, giving me their own tools. That’s why I used to change the dialogue—to let them be themselves to give their truth. If they are really sincere, they are not acting. My job is just to find their sincerity and their own tools. “Be yourself.” I used to ask them in their own experience and their memory: remember something and then try and give it to me. With professional actors they already have an idea and they can explain anything in a logical way. That’s why you can sometimes have a conflict with professional actors—because they think, no, the character is like that.

So it’s a different way of working. You just have to push them in the center and it’s a question of focus. That’s why I don’t do a lot of takes. I maybe just do five takes per shot, otherwise they are a little bit tired and confused. And I don’t want that. Sometimes I just do one take and I know it’s not possible to get another one more. I don’t believe with non-professional actors that, by acting and acting and acting, you can get excellency. All the philosophy is pushing non-professional actors to be themselves. As soon as you place the camera they can give another image of themselves. I’m always just trying to hear.

I’m always trying to tell realistic stories so neo-realism is my way of making all my movies, and at the same time they have moral questions and moral questions have to deal with Murnau’s work—like in Sunrise, where he wants to kill his wife. So always trying to find a place between the good and the bad. In an aesthetic way, it’s neo-realism and then in the story and mise-en-scène I’m looking for John Ford and Kurosawa, and in a psychological way I’m looking for how Murnau did his work and I’m trying to mix all that.

Lingui, The Sacred Bonds opens in NYC at Film Forum on February 4 and will expand.