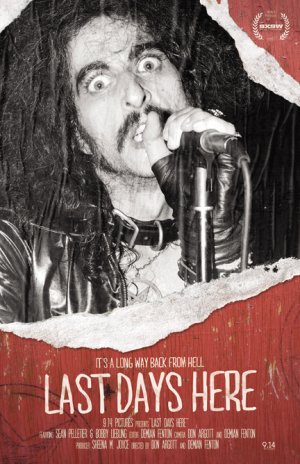

The concept of a “rock doc” can turn off a lot of people. The perception is that anyone unfamiliar with the band or genre in question will be lost to the narrative, or at least bored by a subject they have no interest in. Director’s Don Argot and Demian Fenton manage to prove that this concern is far from reflective of reality with their engrossing documetary Last Days Here.

Chronicling the comeback attempt of Pentagram lead singer Bobby Liebling, Argott and Fenton find a powerful human story worth following and becoming invested in. In fact, their camera takes in moments of such intimacy and personal importance that it’s hard to imagine that they themselves didn’t become emotionally invested in their subject.

So of course, when I got the chance to speak with the directors about their latest film, that question was among my highest priorities. Find out what they said about objectivity, perspective, and the trouble with making a film that has no clear narrative at the outset.

The Film Stage: What was the genesis of this project? How did you first become involved with Bobby Liebling?

Dem: Don and I love old 70s rock, we played in a band together and stuff, we met probably just because we love all the music and became tight and have been working together for a while. When you dig into the old 70s rock vault, you quickly, I think, when you start to scratch at least a little bit into the underground and find Pentagram, and the music’s amazing. It’s like Stooges meets Black Sabbath.

Then you start digging a little bit more and you start to hear about their crazy lead singer, Bobby Liebling, and you hear these tales about, you know, “This guy’s gonna lose his arms because he shot so much heroine,” “this guy lives in his basement even though he’s… his parents’ basement even though he’s fifty-some-years old;” “the guy died on stage and was revived.” Then, through the metal community I met a guy named Pellet, Sean Pelletier, he had been helping Bobby try to get people to actually really hear his music, and he’s helped do proper releases of some of these lost music from the 70s. And we started talking on night at a metal show and just came up with this crazy idea to try and make a documentary.

What was it like the first time that you actually met Bobby in person after having heard all of these crazy stories. What was it like to come into contact with the man behind the legend?

What was it like the first time that you actually met Bobby in person after having heard all of these crazy stories. What was it like to come into contact with the man behind the legend?

Don: The first day that we went down there, like we do with all of our projects, we do some exploratory kind of research, and if we really feel like there’s something there that we should take to the next step we’ll go out and do some initial shooting. And I think that that particular day – out of all the other projects that we’ve done exploratory things – I don’t think there was anything that would compare to that first day that we spent with Bobby, a lot of which is actually the first scene of the film. Bobby showing us his old clothes, and a lot of the early interviews and stuff that is in the film is from that first day. It was really… it was really amazing, frankly. We knew that we had an amazing guy, and amazing personality, in Bobby.

The question was, at that point, after we left we spent about five hours with him and asked him questions and he showed us around, and like I said a lot of that stuff is in the film. Our ride home, we just couldn’t stop talking about, like, “what the hell, what are we going to do with this? We can’t just watch a guy destroy himself in a basement and eventually died. No one’s going to want to see that.” Certainly that’s not the film we had any interest in making.

But, you know, I think Dem has said this before, on multiple occasions; the one time that you could always see that glimmer or that fire in Bobby was when he was dying to play his music, and whether it was his music or somebody else’s music, he had this kid-in-a-candy-store kind of look in his eyes. Whenever he’s like, “I gotta play you this, I gotta play you this,” and you saw, even as damaged as he was, there was excitement about music. So I think that was the one thing we latched onto, no matter what we’re like, “you know what, this guy has a shot.” There’s still something, he’s still really moved by music, and if anything is going to save him it’s going to be that.

So we really stuck with this thing for years, not knowing probably two years into it whether it was going to be anything. We just didn’t know. Bobby’s life is, as you can see in the film, it’s a lot of stopping and starting. It’s a lot of almost getting there and then never getting there. So that’s really difficult from a filmmaking standpoint of trying to develop some story, some narrative, and just when you start on one that seems promising it would fizz out and nothing would happen. So I think because we were able to stick with this as long as we did, we were really able to craft a really, I think, an honest document of Bobby’s life in that pivotal time, when he was trying to get his, when he was really trying to pull it all together.

Like you were saying, it’s really difficult with all the stops and starts to know exactly where a story like this is going to come to an end for a documentary. Throughout the shooting, did the end point ever change or move in a way that was especially unpredictable?

Dem: The end point changed a lot. I mean, as Don said we would start following what we thought would be the arc of the film and it would completely dissolve. So at one point, initially, he was going to make a record, he was initially going to do it with other, bigger name artists at certain points, and then that would evaporate. And then it kind of dawned on us that there were kind of two endings that worked. And when you see this film you kind of see that there are kind of two main characters.

You have Sean, Pellet, he had one kind of goal, which was this kind of Rock Doc, “let’s see Bobby play one last show and get the glory he never got, or deserved.” That was one goal, but we realized that Bobby’s goal was way different, which was to live a life that had been basically, essentially on pause for like thirty years. So the film kind of has a journey where you get to the climax of this film and one goal is figured out and you understand whether that kind of works out or not, but really we needed to gauge Bobby’s life goals and his situation there.

So it took a little while to figure that out, and it’s a hard thing to weigh. There’s no, like, because you played the rock and roll show, or you didn’t play the rock and roll show, that doesn’t convey to the viewer that these people succeeded or didn’t succeed in kind of living a life again. So we had to work harder to gauge that.

In the film those two different strands of narrative really do come through; the difference between the goals of Pellet and Bobby. Because of that clarity and because of the intimacy of both of those, was it hard to maintain a necessary distance from everything that was happening? How invested did you become in these two subjects on a personal level?

Don: Dem was really the guy that was on the ground doing a lot of the initial shooting because we were making two other films in the background. So when things were going on Dem would usually go down and pick up a camera and shoot. And I think it’s definitely, you can see it in the film, and the type of film that it is, it really is an intimate character piece and you don’t get the sense that there’s a crew of people there documenting Bobby. You get the sense that Dem’s in there by himself, which was the reality, and sometimes it was both of us, but most of the time it was Dem with a camera. And I think because of that, you totally get involved in Bobby’s life. And Bobby’s life is a whirlwind, and I think Pellet said that at one point that Bobby has all this shit going on in his life and all this turmoil, it kind of sucks you up into it. And I think when you’re around Bobby, that’s the reality of his life at that point. It was pretty chaotic and you get sucked up into it, and it’s not as simple as doing a sit-down interview and getting somebody’s feelings. There were times when Bobby was in jail, there were times when Bobby went missing. Those are real life things that it’s kind of hard not to get invest in, and I think Dem should obviously talk more about that.

Dem: Yeah, I think that you completely get invest in the situation. Pellet, one of the best things about making this film is that Pellet is a great friend. I still talk to Bobby’s mom all the time. I was just at Bobby’s house over the weekend. These people… we went on a journey, and we went on a journey at a really interesting and critical time in a man’s life, together. We all helped one another through each journey. I had the film thing going on, and Bobby had the life thing going on, and Pellet had the musical goals for Bobby and himself, and you start to care about each other’s goals. And certainly Pellet was a buffer for us.

Like when Bobby goes missing and is in jail, Pellet is the guy getting Bobby out of jail, we’re not getting Bobby out of jail, so we’re certainly concerned, but it’s not us going to do that stuff. So without Pellet it would have gotten really… I think, murky. But Pellet was always there, trying to do the right thing. That’s not to say that I didn’t get phone calls from Bobby’s mom, worried, and that I didn’t care about Bobby or I didn’t worry about him, or that I didn’t get frustrated with him or all these things, or I didn’t… I certainly wanted to see him do well. But I was willing to document whatever happened.

And how hard was it, when it came down to the creation of the documentary itself – the editing, and all of that – to find your way back from that area where you cared about it personally and just look at it as the raw materials to making something of your own?

Dem: You know, I think it’s really odd because we would have this discussion in the edit room. Bobby and Pellet became friends, but when we’re in the edit room they’re subjects, and we have note cards on the wall, and we’re talking about three act structure, and we’re talking about all these things that happened. So I don’t think that’s too hard for us, because we’re used to doing that with all of our documentaries, you know? You meet people and you end up in these places where you care about people. I don’t believe there’s objectivity in nonfiction filmmaking. But we’re good at separating ourselves, I think.

So it wasn’t hard at all in that sense. I think what was hard is to take a step back and really, knowing what happened in reality, and cutting scenes that you felt were balanced enough on either side, to appropriately convey to the viewer the truth, or… the word truth in documentary, again, is a tough road to go down… but to convey the feelings and emotions that were happening that day. Some moments Bobby’s an angel, some moments Bobby’s a devil, but most of the time he’s in between somewhere. Some moments Pellet’s an angel willing to do anything for Bobby, but there’s some moment’s he’s completely pissed off with him. And being there we really felt those things, and being immersed in it, and really wanting to translate that to the film.

And working together, as a pair, did that help in finding that kind of balance, like you said, between the reality that actually occurred and what you have to place on screen?

Don: Yeah, I think that we were definitely fortunate to have the working relationship that we do because we both are able to maintain… have some level of perspective throughout the process that the other person loses inevitably. And I think that’s just one of those really fortunate things that we do have, that we’re always able to… it’s never just one person shooting, editing, directing. That’s too much for one person to do, and it’s really truly a collaboration when you put something like this together. And unlike the other film’s that we’ve done, you know, I’ve done the majority of the shooting so it’s nice to have somebody putt he film together without me being there every step of the way, and so on this film, since Dem did the majority of the shooting, I felt like, “let me take a stab at that, let me sit in the editor’s chair and rough out this thing.” Because there’s nothing more daunting in the world than looking at a hundred-something clips, a hundred hours of footage in a blank timeline. That’s a rough way to get started on a project. But having that happen, I felt like Dem, we were just coming off of another film that was a long edit, and I could just see that it was going to be a long road of trying to get motivated to do this film. So I was like, “let me take a stab at it and put something together.” And once I put a rough thing, blocked stuff out on a timeline, it became a lot easier for us to pop in and out and help move the process forward.

So I think it was also a nice thing to be able to… we all wear different hats and the common goal is just to make a great film at the end.

Dem: And to that, I think we have a really nice balance. Again, Don was saying, I think in this interview, that it’s mainly three people here that work on the films in the various capacities, and the third person on this film, Sheena Joyce, our producer, you know Don and I are metalheads, we could listen to… I dunno, raw interview footage of whoever, Jimmy Page, and it’s fine for us.

So we needed to figure out, you know, show it to someone with totally different perspective too, so when Pellet is so in love with his music or we’re in love with his music, we need to take a step back and show it to someone with perspective, to again maintain that balance, play things for Sheena, who would come in and say, “this is how this is reading to me.” Someone who wasn’t there, who doesn’t know anything about Pentagram, and it was really important to us, when making this film, from the get-go, we knew we didn’t want to make a Rock Doc, Pentagram history piece, Pentagram advertisement. We wanted to make a film with real universal emotions, and a real journey. And I think we succeeded in that, and a big part of that is the way we approached the tone of the film and the place where it comes from.

What’s the greatest issue when you’re trying to do that, when you’re trying to take a subject that seems so niche, and so particularly geared towards one group of people and make it something universal.

Don: I think that’s the hardest part of any film and a lot of it has to do with distributor, and a lot of it has to do with writers, critics, things like that. Things always tend to get boiled down into some kind of box. So it’s very easy to say, “this is a Rock Doc, and this is like Anvil,” there’s already been a ton of comparisons already, and nothing against Anvil, it’s a good film, but this is not Anvil. The only similarity it has is that there’s a heavy metal component to it. But that’s it, and I think our film is, much like their film, it’s less about the music and the band, even though I think that film is more about the music and the band, and their relationship. This is really more of a character piece with music as a backdrop. It’s always a challenge, people want to put this in a box, they want to say, “oh, it’s a Rock Doc,” and the danger in that is that is excludes and alienates people that really would like it, but they say, “I don’t know anything about this band Pentagram, I’ve never heard of ‘em, so therefore I don’t want to see it.”

So I think it limits the audience and we’ve been fortunate enough to show this film in front of varied audiences, and we showed it at Sarasota Film Festival, where most of the people in the audience were mostly over sixty, and they loved it. Not to say that we’re going to go after that market, but it goes to show you that the film transcends the Rock Doc monicker. I think the best reviews of the film that we’ve read, and the best articles say, “you don’t have to know or like anything about heavy metal or Pentagram to enjoy this film.”

That’s the one takeaway I would love people to be left with.

Dem: I’d actually say it’s a better experience if you don’t know anything. In this day and age of the internet, heavy metal publications and web sites, if you’ve been following Bobby’s story, you know a little bit about what you’re going to step into. But if you haven’t, it’s such an amazing journey, it’s great. To that end, speaking a little about getting to these universal issues, I think all my favorite documentaries, they’re about a literal certain subject, but they completely have to transcend that and get into these universal issues that that story kind of provides. And when you start to break those films down and you look at a movie like Crumb, there’s not as much drawing in there as you’d thing. Or you look at a film like American Movie, there’s not as much movie making in there as you’d think. And those are my favorite types of movies.

I’m actually from DC, so I have a basic amount of exposure to Pentagram. I have friends who have been to some of the shows and knew the story. But on the whole I was pretty ignorant about it, so I do agree that you were able to make something that was very accessible to someone that wouldn’t have much idea about it, and it did resonate with me on a very human level. So that was really impressive, and I really liked that aspect of it.

Dem: Thank you man, that’s a huge compliment. I mean, that was our, from day one, that was out initial goal with all of our films, I would say.

Wrapping up, do you think, now that you’ve reached this one point with this story, would you ever go back to it and maybe do a five or ten years later and just see what’s happening?

Dem: You know what, I would immediately, normally to a question like that say “no,” but in this case I will certainly not say no. Who knows.

Don: Who knows.

Dem: Who knows with that. I was over there over the weekend, and I felt there were moments when I wished I had a camera still. So I will not say no to that.

Last Days Here is now in limited release.