It’s a rare thing when a director can enter a foreign land or culture and create a film that feels so authentic that it feels as though it were directed by a native artist. Joshua Marston pulled off just such a chameleon-worthy feat with his debut feature film, Maria Full of Grace.

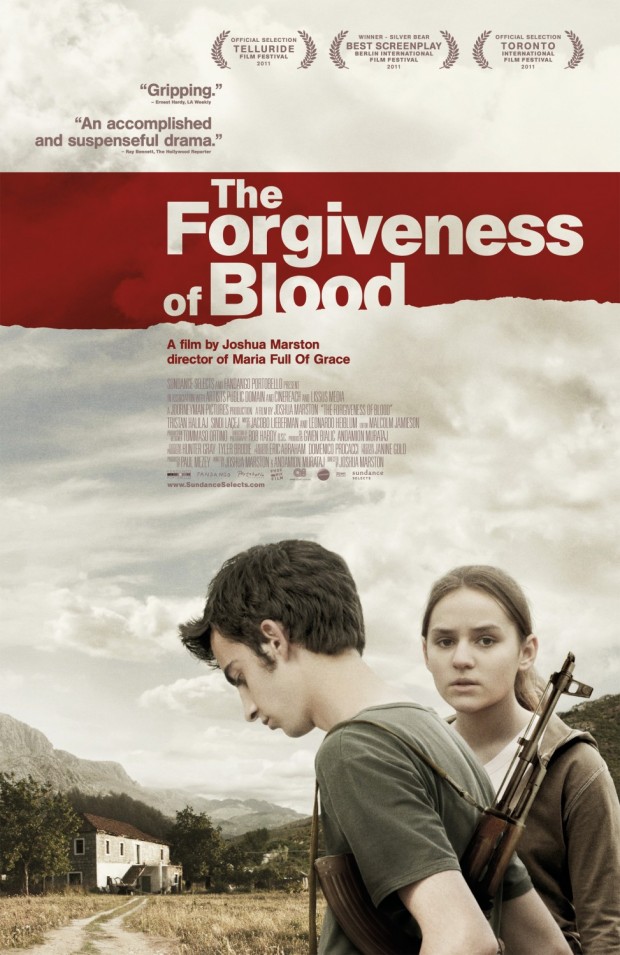

Now, Marston applies the same skill for depth and authenticity with his follow-up, The Forgiveness of Blood. Set in present-day northern Albania, this film tells the story of Nik, a teenage boy living a modern life who suddenly finds himself isolated in his own house thanks to an ancient law that says a male from one family can be killed as retribution for the murder of a member of another family. These “blood feuds” can last for years, and forgiveness and absolution are hard to come by.

Marston spent over a month in Albania interviewing, casting, and working with native co-writer Andamion Murataj to create this film, and the evidence of this commitment to a fully realized and nuanced reality is up there on screen. I got a chance to talk with Marston about his experience researching and shooting this film, as well as his thoughts on what this film will accomplish, how fiction and documentary film differ in their impact, and the future of the institution of blood feuds in Albania.

The Film Stage: I know that in doing your films you do a lot of research and I was wondering how you were first exposed to the concept of blood feuds in Albania.

The Film Stage: I know that in doing your films you do a lot of research and I was wondering how you were first exposed to the concept of blood feuds in Albania.

Joshua Marston: I first became aware of Albania reading about it here in the States, reading about it in the newspapers. There are periodic pieces in the news here about Albania and general what’s covered about Albania here are the blood feuds, because that’s the most fascinating and intriguing story about Albania. But the thing that specifically caught my attention was not the feuds themselves but sort of the ramifications of the feuds, which is to say the hundreds of families that are living in self-imposed house arrest because their family, some member of their family, has killed someone and so they owe a life in return. And it was the idea of, well, what is it like, what would it be like to live in those circumstances especially if you’re, you know, a teenager who wants nothing but to be out and about in the world. So, more than anything it was really a story about the juxtaposition between the old and the new.

To that point, your film does show the teenager, Nik, and even his sister and how they’re not of the same generation as their parents or their grandparents, they don’t see these feuds as having the purpose that the older generation does. Nik even rebels against it and his sister sort of uses it as an opportunity to kind of give herself a position in life that she would not have otherwise had. Given your time researching this in Albania, would you say that these kinds of choices that you chose to portray in the film the most common reaction among the younger generation?

Well, I did find that the younger generation doesn’t really, generally speaking, have much interest in these feuds. They’re not as steeped in the old way of thinking. And in particular young women, girls, are frequently frustrated by the old guard mentality. In my casting, I interviewed thousands of kids, and it was the girls, in particular, when I said “what is the most difficult thing about being a teenager in Albania,” they would complain about the mentality of their parents generation.

And it did extend somewhat to the mentality of their older brothers. There is a paternalism, and it is a patriarchal society. There is a gender bias. And so in that respect the kids are still caught up in a certain way of thinking. But the kids don’t have an interest in extending the feuds. I didn’t find very many kids who if I said, you know, “if someone killed your father, would you pick up a gun?” Or “If someone kills your brother would you pick up a gun?” Most of them said “no I would let the police handle it.” Yet they are still stuck inside of it, because even if they don’t want to pick up a gun in revenge, if someone in their family has done an act of violence or killed someone, like it or not the other family might choose to target them, and then they really have no choice but to be constrained by this way of thinking.

Were you able to find any young people that did embrace or accept and defend the institution of blood feuds?

No, not specifically. People don’t necessarily embrace the notion of blood feuds but what you find a little bit, it’s a little more complicated in the sense of what still pervades and persists. What’s still pervasive and what persists is the significance of honor in Albania society.

And so, it’s a place where it might be a little more difficult to back down when a conflict arrises than you might expect. And if someone insults you or impugns your masculinity then, even in the younger generation, there is a strong sense of the importance of maintaining and protecting one’s honor. And I think really that’s what’s underneath the problem with the blood feuds, and that’s what makes it such a difficult thing to combat.

In that same vein, while you were there doing research, did you see any kind of larger societal shifts regarding that, or was it one of those things where, the longer you live with it the more you become accustomed to it and risk carrying it on?

While I was there I watched Albania celebrate their joining NATO. And there was a lot of discussion about joining the European community. So, people in Albania are definitely thinking forward and looking, you know, with great anticipation at the prospect of joining modern western Europe. And you know, you look all around you when you’re in Albania, there are cell phones and Facebook is incredibly popular, and there are traffic jams full of Mercedes Benz, so the modern way of living is completely pervasive in Albania.

But there are still these older way of thinking, the signs of this older way of thinking, and I think that it’s still the two things still coexist, and I think that is what is so fascinating about Albania.

As the older generation fades away and this younger generation, that’s more in tune with technology and cell phones and Facebook, is the blood feud the type of thing that will eventually fade away, or will it now be carried on through the younger generation? Do you think that they will eventually become the type of people who will continue on with that tradition?

I’m hopeful and I’m optimistic that the blood feud is fading from Albania, but at the same time I’m a little bit sober in my optimism, in the sense that it is something that dates back hundreds of years. And for 45 years under communism the dictatorship proudly declared that it abolished blood feuds and that they no longer existed in Albania. And it seemed like minutes after the dictatorship fell that Albania’s were turning back to the Kanun and the old way of thinking. So this idea that it’s gone or its going or its diminishing…it may be diminishing but whether that means that it’s on its way out. It’s hard to say.

I’ll give you one example. I would ask people, you know, “would you pick up a gun and take revenge?” I might ask that of a younger kid, and of course people would give you the answer you’d hope they’d give you, that they wouldn’t want to. But the bigger problem, the other way of asking the question is, and I asked it to a mayor, a former mayor, who is a lawyer and who was very well dressed and is clearly well educated, and we were in the middle of a conversation and I asked him, “you know, if the phone rang right now and someone called to say that your brother had flown off the handle and killed someone, what would you do?” And without batting an eye he said, “I’d go straight home, lock the doors, lock the windows, and I’d stay inside and I’d call a friend and I’d have my friend get my kids out of school and I’d bring them home. And we would stay inside of the house until we were told it was safe.”

On the one hand people might claim that they don’t want to pick up a gun, it still exists, and that fear still exists, and it’s still sort of in a way this knee-jerk reaction, and it’s still the expectation that a killing can produce a feud. That hasn’t gone away. Whether it will go away in the future, whether it’s diminishing, you know, I’d like to be optimistic, but I just can’t, I don’t think anyone can say.

To that end, in creating a film like this, obviously there is the entertainment angle – that is film’s primary mode – and it also is very informative, but do you also hope kind of hold out hope that it might spur some greater action from the world community at large regarding blood feuds?

I do hope that the film spurs some sort of action, I don’t know about the world at large. I think that there already is a fair bit of pressure from the European community on Albania that they need to get this problem resolved before they’ll be admitted into the club.

Within Albania my hope would be that this film might push the conversation forward insofar as it enables Albanians, who are already well-versed in the problem, to understand it from a different angle. I think there’s maybe not so, there haven’t been so many…there have been plenty of films about feuds. But I don’t think there’s ever been a movie about feuds that’s been from the point of view of the teenagers and the experience of isolation. And so I, my hope would be that this would certainly spur some conversation and some action.

And I know that after the movie was released in Albania, there was a meeting, a conference held with a number of NGOs that work on the feuds, and there was some discussion, for example, of using the kids who were the actors in the film to be part of a publicity campaign against blood feuds.

Well, that is pretty impressive. From that angle, especially talking about the actors, for you personally, what was the greatest challenging in creating this story. You know, it’s a culture that is seemingly so foreign with this concept of blood feuds, and not only that but you’re using native actors and locations. So what were the hurdles involved in creating this story, in the face of all that?

I think the one, the biggest, was the logistical challenge that there simply isn’t a well-developed film industry in Albania. They shoot maybe one to two films a year, and so if someone else happens to be shooting at the same time as you, or if, as was our case, you happen to be shooting outside of the capital up in northern Albania, it becomes very challenging to find crew, for example, or to find people who are used to working on film sets and understand the way things operate.

Another challenge that I didn’t predict was, in dealing with locations, you know, a lot of blood feuds are, not surprisingly, started over fights, because of fights over land. Because after land was nationalized, under Communism, the de-nationalizing of land, or the privatization of land, brought up a lot of conflict. And that I hadn’t really forseen, it would extend it’s way into our locations department. So what were dealing with, people were renting, for example, the main location that had to have two houses on it, was discovered that the two houses, even though they’re owned by two members of the same family, they were first cousins, there can still be quite a lot of squabling between them.

In one case, we were shooting — our opening scene of the movie is a shot of a house and a path that a cart goes along. To create that path we had to get permission from I think six different families because the land had been so parceled up that it ran across a lot of very very small parcels. And getting the cooperation and the coordination of those people was quite a challenge. And then when we had done all that it turned out that the person who owned the main house had a brother, they had inherited it together, and the two of them were not exact, didn’t exactly see eye-to-eye, so that was quite a challenge.

You excelled in this film at creating a kind of narrative accessibility. Especially for outsiders, people like myself, who didn’t really know much about this country, or the institution of blood feuds, and yet you were able to do it with purely insider’s eyes. What was the greatest tool in creating that tone of inside accessibility, but at the same time guarding against becoming reductive or pandering?

I think the greatest asset were the actors themselves, I think that was, for me, the way I work with actors is to be extraordinarily collaborative. So that meant working with the actors to define their characters in a way that made sense to them, so that everything, story-wise, had a strong anchoring in decisions made by characters who felt real and honest because they were created by people who lived in present day Albania, or who know present day Albania. You know we would have some of the actors who were from Kosovo and Macedonia. It’s the fact of collaborating with those actors who know the world so intimately that enables me to then, from that starting point, create everything else with a real sense of authenticity.

I assume that that takes a lot of trust in the actors to, coming in as yourself as an outsider, to trust them in kind of giving the film that feel.

Yeah, we have to trust each other. You know, they had to trust me as an outsider, I think one of the things that enabled them to trust me was that I had done my homework about blood feuds, and about, and I was able to clearly articulate what it was I wanted to represent, why I wanted to make the movie. And I wasn’t just interested in representing Albania as some backward primitive place, that what I was interested in was the complexity of the country in the present day. So I think that made them interested, and that made them wanting to engage in the conversation. And it was those conversations that lead to the creation of the world of the movie.

In cases like this, do you think that narrative film, in a fiction sense, holds any kind of advantage over documentary filmmaking? Is there something you’re able to do with this that a documentary wouldn’t be able to capture?

I think the main, there are two main advantages. One is that the general public seems to prefer narrative films, partly because they may, by virtue of the use of camera or any of the other cinematic devices, create a world that somehow drops one in to the story more fully than the documentary does. I actually think that documentaries can be enormously powerful, but the two forms do it in a different way. And I think as realistic as this film feels, I think it’s the fact of knowing that you’re in a story, as opposed to in real world, allows you to engage, perhaps, emotionally, in a different way.

And then the other advantage is that I think you simply, you’d have to be extraordinarily lucky, I don’t know how you could ever manage to find characters and tell the story with real people that I’m telling. In the same way with Maria Full of Grace, you would have had to have found a girl prior to swallowing drugs, document her, then have her allow you to get on the plane with her, and she would have had to incidentally gotten on the plane with three other people. I mean, that’s just not likely to happen.

Have you ever considered trying to do a documentary?

Yeah, I have a great interest in documentary and I would love to do documentary and I will do documentary, but I will also continue to do fiction films.

Do you have any kind of ideas or concepts of what you would prefer to do a documentary on?

If I did, I don’t think I would yet speak publicly about them. (laughs) So you’ll know it when it’s ready.

The Forgiveness of Blood is now in limited release.