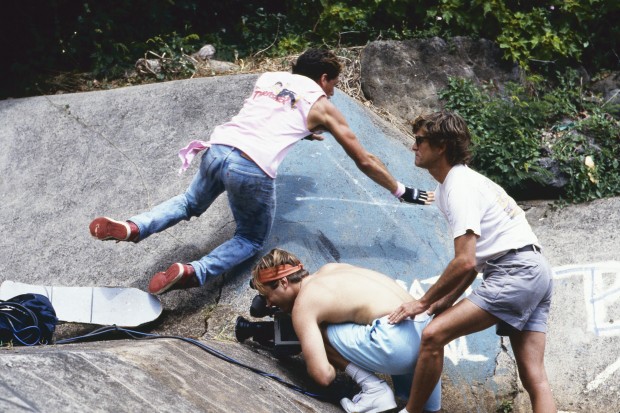

Bones Brigade: An Autobiography wouldn’t exist without director Stacy Peralta. Creator of the group, he selected a bunch of young, talented skateboarders and brought them together from all over the country. Unlike the Z Boys that he was part of in the ’70s, this group didn’t hang out on weekend — they were put together as a competitive workhorse, while still having a bit of fun. However, the time for skateboarding was in flux, and it wasn’t easy to keep the team together.

The documentary Bones Brigade ultimately showcases how these skateboarding legends came to make a name for themselves and effectively shape the sport for generations to follow. Earlier this week I had a chance to speak with Peralta to discuss the fashion of the ’80s and how we can both laugh at it now, what he looked for in bringing the group together, whether he thought twice about showing the ridicule leveled at Tony Hawk, how he set about doing the various interviews, and much much more.

The Film Stage: This documentary makes a point very, very clear. Skateboarding was almost a cultural flash in the pan. And we see how it rose up again and now it is what it is. I’m curious if you directly did anything to bring it back or was it all going on around you?

Stacy Peralta: No, like I said in the film, we did two things. We returned the contests to backyard ramps, which meant a great deal. We helped create street skating. So more than anything, it was that first skateboarding video that went all over the world and showed kids for the first time what modern skateboarding looked like, how to do it, and what kind of terrain skateboarders should skateboard on. We worked our asses off to try and build the sport back up. It seemed fruitless and almost insane a couple of times during that time. But we finally turned it around. It was very close for a few years, let me tell you. It was really questionable whether it was ever going to come back.

One thing I found curious is that skateboarding for a long time was this counter-culture thing. The team that you put together for Bones Brigade, for better or worse, they seemed to not be interested in the counter-culture aspect. They seemed to just find themselves. They weren’t rebellious teenagers, they were just kids that found their passion in skateboarding. Was that a conscious effort on your part or was that just a natural progression of getting great guys and putting them together?

I think it was a combination of both. I tended to pick guys that were like that. I tended to pick skaters that were probably a little bit more serious about what they were doing and less interested in the fashion and the philosophy but really wanted to make a difference. At the same time I think that I probably pushed them to be that way because I knew that that was the only way they were ever going to make something of it. So it was a combination of both, I think.

I’m glad you brought up the fashion. I walk around in daily life now and skateboarding has really invaded popular culture as far as fashion. Whether it’s Volcom, Vans, DC, and others. You were growing up and you were riding this wave, and it’s hilarious but if you look back at the ’80s fashion and it’s not something that you think is fashionable. Was that skateboarding clothing fashionable back then?

Ha! That’s so funny. Yes, it was—if you can believe it or not—fashionable at the time. Of course, you look back now and it looks idiotic. Short shorts and that sporty look with the color combinations. That was hip back then. But God, you look at it now and it’s hideous.

[Laughs]

But every decade has that. The ’70s had the disco decade, which was flash. But you look back at disco now and it’s just dowdy. It’s ridiculous. But back then it was cool. So, yea, back in the day, these guys looked very hip. What they were doing. How they were dressing. But man, you look back now and it just doesn’t work too well.

You mentioned how much effort you and all the guys went through to try and bring this sport back. At any moment did you look at things and say, “It’s back”?

Yeah, I think there was a moment where we had a contest. It’s actually in this film where the tail of Lance [Mountain]’s board is on fire. It’s a ramp contest in the middle of a forest. There’s about 500 to 600 people there. It was at that contest, which was probably in 1985, that I realized, “I think this is coming back. I really think this is going to happen.” It just seemed obvious that people were reigniting. There was a tremendous amount of interest and people were starting to show up again. I think that was the moment.

You went through a lot of effort it seems to get both sides. It’s striking because I was born in ’86 so by the time I became aware of Tony Hawk, he was already a major figure in this industry. But you paint this picture about Tony being labeled as this boy scout and not having any passion, but instead being very technical and precise. Did you struggle with maybe not painting that picture?

You mean was I concerned about showing that part of his career?

Yeah, were you hesitant about that?

No, not at all. It’s very easy for kids to look at Tony today and just assume that he stepped into his success. But I wanted to show kids that Tony struggled. Tony did not have an easy road. He was not accepted at first. He was considered a robot; a circus acrobat. People didn’t understand him. I thought that it speaks to his character that he worked through that adversity and proved everybody wrong. He has become Tony Hawk, the most recognizable alternative athlete in the world. There’s a lot to be said about that. he didn’t have a red carpet for success. He really worked to get where he’s at today and I thought it was very important that we do the best we can to tell that story so kids can realize that it’s a struggle to follow a dream.

Was it interesting to try and gather these alternative opinions and all of these characters? Was it fairly easy?

It’s never easy. I wish it was, but it’s not. It’s never easy. I have to write so many questions for so many people… and they have to be poignant questions and intent questions and intuitive questions. Then once the interview starts, I have to take that person somewhere and I also have to listen to where they’re taking me. In the case of Rodney Mullen, he took me to a place that I had not planned for. he was really responsible for steering his interview in the direction it went. At one point I kind of threw my questions away and just followed where he was going. That’s part of the skill of being an interviewer is knowing when to let go and when to follow. That’s just about listening. And Rodney, like Tony, also discussed and talked about and was very open about the struggles he had with his father, who was always threatening to take his skateboard away because he thought skateboarding was a waste of time and a waste of Rodney’s future. A futile thing to do with the rest of his life. I was hoping the film would take on some sort of a significance. It was those guys telling their stories that added that significance to the tale of the film.

You mentioned that you were the interviewer, and that was actually going to be one of my questions. They never pan towards you asking the questions. You’re always off to the side or in front of them. Did you ever think about having a proxy interviewer or was it always going to be you?

No, they actually wanted it to be me. In fact, Rodney has told many people, “I don’t think I could have opened up like that to someone else.” This is not to say that someone else couldn’t have done it, but I have that kind of a relationship with those guys. I did have someone else come in and interview me. That same person that interviewed me also did second interviews with all of the guys. Whenever the guys were talking about me, they were always talking to the second interviewer. So I conducted the bulk of the interviews, then I would step out and the other interviewer would come in and he would then talk about their relationship with me. That’s how it worked. We did all the interviews in one week on one set, for about six interviews a day.

There’s a poignant moment where Tony, and Rodney as well, kind of mention how there’s so much pressure put on them to not only win, but to continue winning. Just over and over. Every competition. There’s something to be said about competition as life and how daunting that can get. You’re the coach. Maybe not in label, but you were pretty much their coach; their guidance counselor; their parent in a way. Did you worry about that? Did you try to bring them out of it or did it sneak up on you as well?

Both of them kind of snuck up on me. I didn’t realize how bad it was for Tony until Tony’s brother brought him to my house. I knew Tony had been through struggles but I didn’t know it was that bad. It was the same with Rodney. When he came off of in this one contest and said, “That’s it. This is it for me.” he was so tense and so uptight and so unlike himself. Like I say in the film, I was a young kid at the same time. I was trying to figure out their issues and do the best I could from a psychological standpoint and an emotional standpoint. Even from a big brother standpoint. It was very challenging. I never put pressure on them to win; I only put pressure on them to do their best. That was the most important thing: show up and do your best. There was many times when they didn’t when and there was no issue, whatsoever. As long as they came there and they were showing off a new trick, and they were keeping up with the rest of the pack, that’s all that mattered.

You mention that during one of the skate videos, you showed these guys doing the street stuff and having fun, but also wiping out here and there with some accidents — it humanized them a bit. Yet, outside of one bad fall from Tony that ended up with him having a concussion, you don’t show any big falls or injuries or wrecks. What was the decision behind that?

You mean did we ever show them breaking a bone?

Breaking bones or anything big where it puts into perspective the danger of this sport.

To my awareness, none of those guys ever broke any bones.

Wow!

That I’m aware of, they never did. I don’t recall any of them ever breaking and arm or a leg. Tony got a couple of concussions when he was very, very young and broke a couple of teeth. But once they got going, I don’t remember any serious accidents. [Mike] McGill is shown in the film in a picture with a cast on his leg, but it wasn’t from a broken bone. It was from something else. He had cut himself terribly on a ramp from a nail or something like that. But yeah, they never had any serious accidents where it took them out for a long time.

That’s kind of incredible.

Yeah, it was pretty surprising. But that had to do a lot with the science of knee pads and the new technology in what they were wearing and riding. Also, the new style of terrain that they were skating as well because the terrains that they were skating was actually designed for them. It was not like a backyard pool that was designed really for swimming. These ramps were designed. The transitions were formulated for skateboarding. It helped lessen their accidents.

Bones Brigade is now in limited release and VOD.