Great directors, like adventurous travelers, explore new lands not trying to impose their sensibilities on them but allowing the foreignness to wash over them and reveal new layers that complement their worldviews. Although Hirokazu Kore-eda’s entire filmography has been set in his native Japan, within the very first few minutes of The Truth––his first film set outside of his homeland––he has taken the riches of France and filtered them through his soul-stirring humanism.

As Lumir (Juliette Binoche) arrives in her childhood home in Paris, accompanied by her American husband (Ethan Hawke) and their young daughter (Clémentine Grenier), the golden sunlight that throughout the decades lit the works of Renoir, Clement, Truffaut, and Bresson, suddenly seems more meditative, like it will be able to warm more than the characters’ bodies and reach straight into their souls.

They will all need that warmth as they face Fabienne (Catherine Deneuve, in yet another effortlessly transcendent performance) an iceberg of a woman, who has become one and the same with the untouchable icons she’s played on screen. She has become the walking sleeping beauty of her castle, convinced that she’s under the curse of her friendly rival Sarah, a promising actor who died decades before, leaving behind an unfulfilled legacy which Fabienne has decided to obliterate, shining brighter than she would’ve. But how to know what someone who passed away might have accomplished?

That is where Kore-eda gently imposes his thoughtfulness, as he tells a story about how creating one’s legacy and living one’s life can become competing timelines. As the characters traverse the worlds of their present lives, their memories, and the sci-fi film Fabienne is shooting, The Truth becomes an unassumingly human account about forgiveness and the restorative power of cinema, which like the Parisian sun casts a different light on everyone, reminding audiences, if not always the characters themselves, of their undeniably flawed beauty.

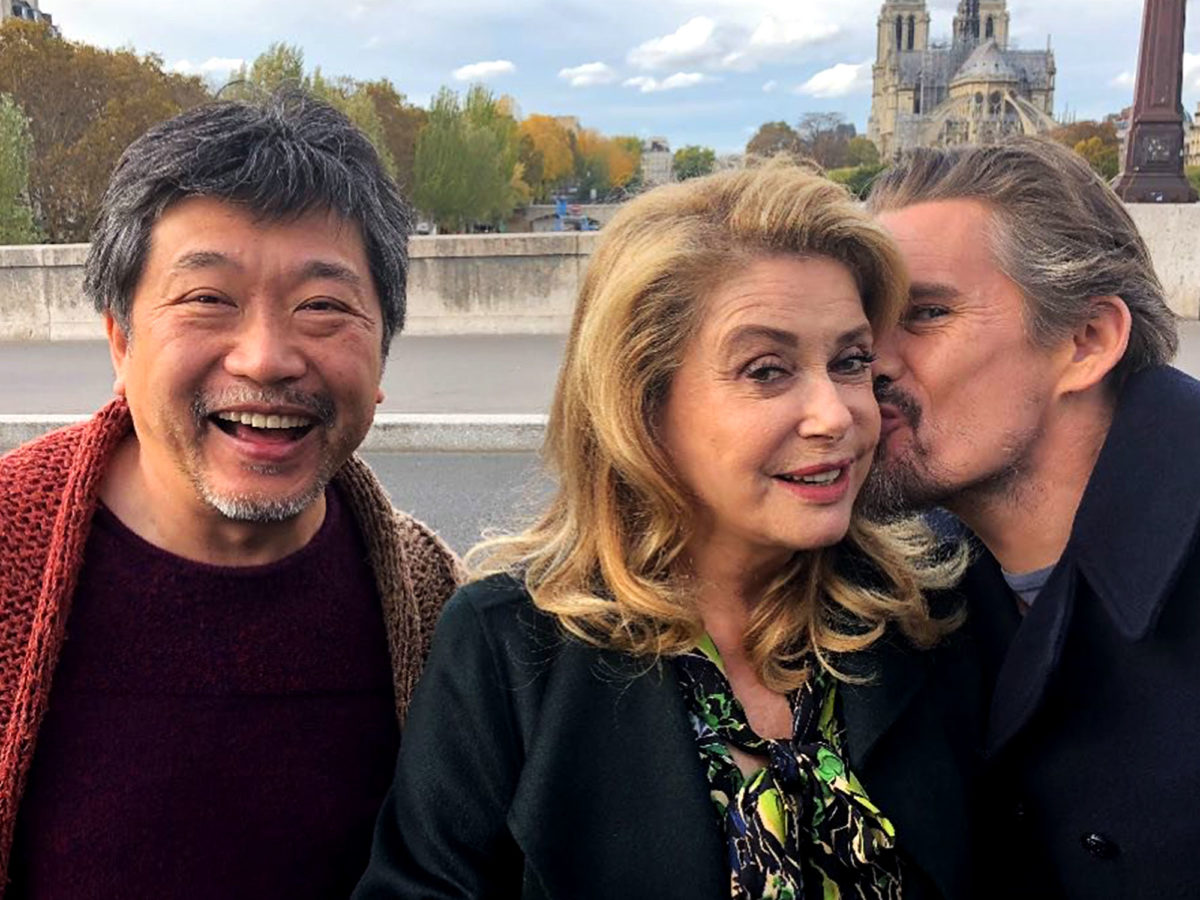

We spoke to the renowned filmmaker about making his first French film, getting to work with actors who once seemed to exist only in his dreams, and how the movies have become indistinguishable from his own memories.

There are almost two parallel films in The Truth: we have the mother/daughter drama, but there’s also a more fantastical universe in which Lumir’s daughter, Charlotte (Clémentine Grenier) gets to live, which is almost like a fairy tale. It made me think of your film After Life, can you talk a little bit about how the fantastical elements came into play?

The film centers around a protagonist that never appears because she died young, but of course, her present haunts Fabienne, because Sarah always remains young, while Fabienne alone keeps aging. I was drawn to that element in the original Ken Lieu science fiction story that the film-within-the-film is based on. This idea of someone aging created a different flow of time for different characters, because you don’t age if you’re dead.

I also saw this as a beautiful metaphor for film itself. You have an actor like Catherine Deneuve, who gets to see The Truth, but she could also see a younger version of herself in something like The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, or any film she made when she was younger. As a filmmaker, this almost gives you the power of a magician, you can capture people’s youth forever. How does it feel to be able to do that?

Hm. I think it’s also possible that the kind of magical powers that you talk about has a quite cruel aspect as well, because if you’re forever young on the screen, but you yourself keep aging the way that Catherine Deneuve does, and in addition, your rival never ages at all––that record of you when you were younger can become a cruel reflection. It’s important to think of the cruelty that’s inherent in that magical power.

There’s a moment when Lumir and Fabienne are talking about The Wizard of Oz, and Lumir tells her mom that she didn’t come to see her when she did a production of Oz, as a kid. I laughed so hard because in that scene Fabienne is dressed in green, making her look like the Wicked Witch of the West.

[Laughs.]

This made me think of how movies become the fabric of our memory. What are some films or scenes that have become interwoven with your own memories looking back at your life?

I would say that scenes from films that have become integrated in my memory would be Gelsomina in Fellini’s La Strada, Deneuve in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, or Leos Carax’s Mauvais Sang which starred Binoche.

You mentioned in an interview that your mother had been a huge fan of Joan Fontaine and Ingrid Bergman, so I’m glad you mentioned films starring Deneuve and Binoche. As a director, what is it like to get to work with people that you idolized in the movies?

Honestly the first time that I called “action” on set and Catherine Deneuve started to speak the words that I had written in my screenplay and take the actions that I directed her in… I’ll always remember that, it will be forever frozen in my memory, because she will always remain someone who I thought was a star of the silver screen but who would never be part of my reality. Working with her I returned to being a young boy who was a great fan of the movies. Starstruck!

In The Truth you capture three generations of women trapped in a mansion that feels like a prison. In Shoplifters, you show three generations of people who live in a small home that feels like a castle. Can you talk about the locations and how their size has little to do with how their inhabitants perceive it?

In this film the mansion where they all live, certainly for Lumir growing up there as Fabienne’s daughter, she was completely confined there. Meanwhile, for Fabienne, she’s haunted by Sarah’s ghost and the legacy of her own career. But the fact is that the mansion we found really had a prison right behind it, so I wanted to take advantage of that to suggest and heighten the sense of the characters being imprisoned in a mansion.

The film is so touching because it captures moments you show audiences, but that the characters themselves never see. For instance, the way in which Fabienne’s assistant looks loving at Charlotte and he knows she is a petite version of her grandma when she’s brushing her hair. Similarly, we see Lumir caressing her mother’s brush, but her mother is not in the room. Why was it important for you to show those moments?

Thank you for your careful viewing of my film. Those two scenes you mention are quite important. The two main characters, although they’re actually unaware of it, are actually guided towards some kind of resolution by the small moments of magic, especially those that the men in their lives who they essentially consider useless are witness to. The mother and daughter are performing for each other and the ancillary characters who become the audience of these moments lead them to a resolution by periodically whispering certain scenes or lines of dialogue to the audience only. That’s how you keep the audience spellbound and the story suspenseful.

You lost both your parents over the last two decades, but you also became a parent yourself. Does being with your crew in a movie set create a new family or does it instead become a constant repetition of loss once the project is over?

You can’t really compare your own family to a film crew, but these past years in Japan I’ve been working with the same crew, and in fact I probably spend more time with them than with my actual family because of all the time I spend working on my films. In that sense it is a kind of alternate family. In France everyone I worked with was new, but we spent about six months together overall and you do form a relationship beyond work. When I do go to Paris and see them again, it’s like seeing old friends which is wonderful.

It’s so captivating how in the scenes where we see the characters in the movie set, you show us the green screen, and we never really know what the final result will be. There’s a beautiful contrast because cinematographer Eric Gautier captures Fabienne’s garden and the sky in such a beautiful way. Do you believe CGI will ever be able to fully recreate the beauty of nature?

I’m not the best director to ask that question because I’ve basically never used CGI in my films. I suppose the day will come when you can’t tell the difference between the real sky and a CGI sky, but I’m not necessarily convinced that’s a wonderful development.

I laughed so hard when Fabienne tells someone “never to trust a cat person.” Does this mean you’re a dog person?

[Laughs] Yes, I like dogs. [Laughs]

But it’s not really reflecting my personal prejudice, it just felt like the kind of snarky remark that Fabienne would make.

There’s a gorgeous moment in which Fabienne goes and looks at mementos from her films to remember the past. If you could own an iconic piece of movie memorabilia, what would it be?

I have just the thing. A long, long time ago I visited Twentieth Century Fox studios and they had a warehouse with old sets and costumes. I saw a full head mask from The Planet of the Apes. I would love to have that.

Thank you to interpreter Linda Hoaglund.

The Truth is now available digitally.