As far back as I could remember, no film has had such a grand cultural impact than Goodfellas. At my high school in Cape Cod, Massachusetts–a far cry from Scorsese’s mean streets of New York––almost every locker had at least one picture of Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Ray Liotta staring with steel-gazed coolness at my fellow students as they gathered their books and rolled up copies of Playboy for Study Hall. When I was commuting to college in New Hampshire, The Rolling Stones’ “Let it Bleed” album blared from my 85’ Cutlass Supreme as I imagined hearing the thumping of Frank Vincent’s body in the trunk rather than the pulsating sounds of “Gimme Shelter” or “Monkey Man.” During late-night sessions with my friends and family, as soon as one of us called each other funny, it was only a matter of time before one of us replied, “Funny how? Like I’m a clown!?”

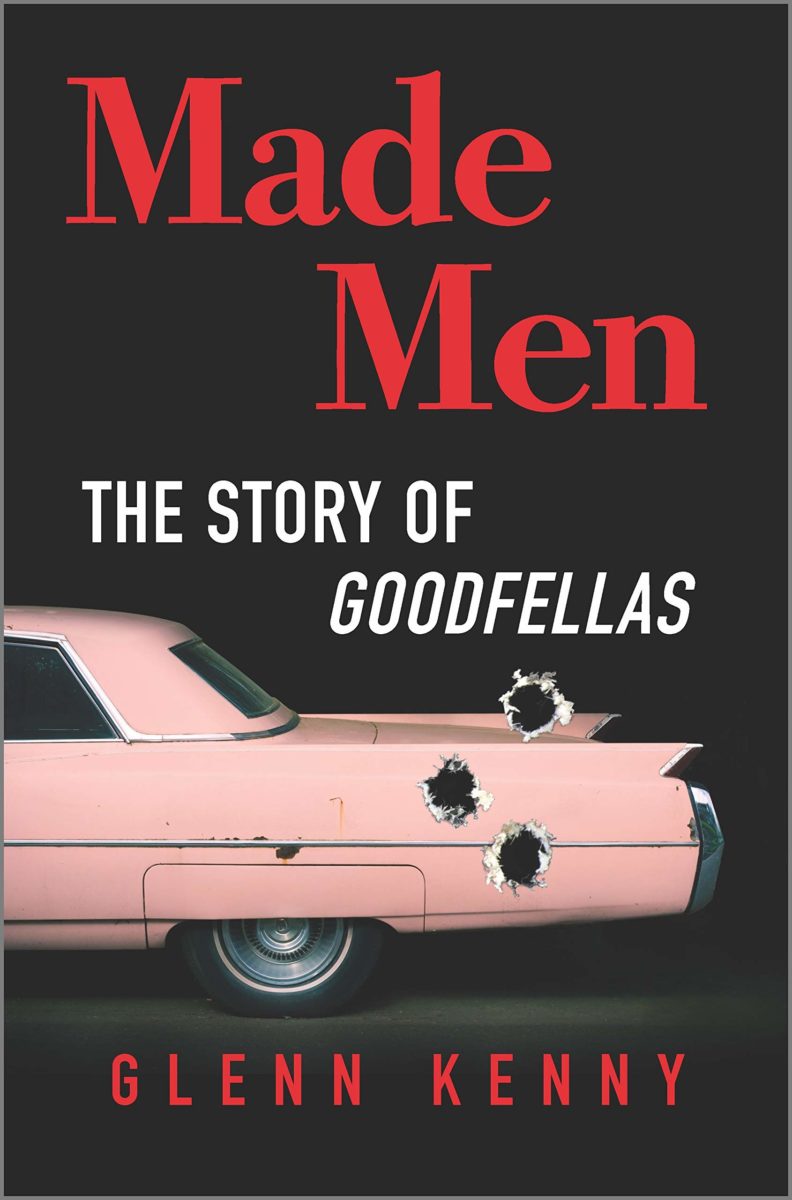

Loosely based on Nicholas Pileggi’s book “Wiseguy,” the story of Henry Hill’s (Ray Liotta) rise and fall in New York’s criminal underworld has been lauded as both a celebration of criminality (“I had a sugar bowl full of coke next to the bed. Anything I wanted was a phone call away. Free cars. The keys to a dozen hideout flats all over the city”) and a cautionary tale that has influenced criminals and politicians alike (“Never rat out on your friends and always keep your mouth shut”). Thirty years after its initial release, Goodfellas has been a film that has not only been a cinematic bellwether for Scorsese’s disciples like Quentin Tarantino, Spike Lee, and Paul Thomas Anderson, but has been the subject of intense scrutiny and unapologetic hagiography from scholars and critics alike. Thankfully, Glenn Kenny’s latest book “Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas” (available from Hanover Square Press) is a riveting and revealing look at, arguably, one of Martin Scorsese’s most revered films.

Like the film, Kenny’s book runs at a pace and energy where there is so much detail given throughout, yet you’re not weighed down by over analysis; it’s like the freeze frame or Steadicam shots with Ray Liotta’s narration chiming in as the book keeps moving along. “When I started this book,” Kenny said from his home in Brooklyn, “I was aware of the fact that this was a movie that has been written and talked about as long it had been released. What was important for me was to find new things to say about it regarding its place in contemporary film history and contemporary culture. A lot of what I wrote was determined on the research, but it was also my intention to create something that was engaging, funny, and fast that didn’t feel like a slog, you know?”

What makes Kenny’s book so engaging is that he highlights the issues of racism and feminism throughout Goodfellas in such convincing detail as opposed to emphasizing the white-dominant masculinity that has plagued film scholarship in the past. As Kenny explains when seeing the film thirty years earlier, “I was aware of those issues just as much as I saw the racism in the characters in Raging Bull. In thinking about Goodfellas today, there’s more to think about. Sensitivity has increased in some circles; there are objections to depiction that are much stronger as they were in the past. It’s true that Scorsese makes most films that are set in masculine worlds, that they’re about men and that they’re about masculine errors, but I wanted to counter a little bit the idea that’s gained some unfortunate currency that he doesn’t care about female characters. I wanted to focus a little bit on the time he spent with Karen Hill and her portrayal by Lorraine Bracco. He channels his own obsessions, as a filmmaker, through Karen’s eyes at a certain point in the film: the sexual jealousy aspect, which usually falls to the male characters in his films––as seen in Raging Bull––now falls into Goodfellas with Karen Hill and her rage over Henry Hill’s affair with Janice Rossi (Gina Mastrogiacomo). Now, obviously, it’s subordinate to a lot of other stuff in the film, it doesn’t get as much time devoted to it or as strong an emphasis, but it’s definitely there. I think it’s interesting and worth talking about.”

With criminality and politics being bedfellows with President Trump in the Lincoln Bedroom, I couldn’t help laugh and reel my head back in shock over the irony of Ray Liotta’s voice-over stating, “Being a gangster was better than being President of the United States.” As Kenny asserts, “I didn’t want to belabor the point. I think it’s pretty self-evident to anybody looking at the situation in today’s politics and the fact that Trump has, in the past, sort of bragged about negotiating with mob figures and knowing their tactics, that sort of thing. The way he uses vocabulary of criminality, it’s right there. A lot of the things in Goodfellas, which is a film a lot of people have insisted glamorized criminality, the mob lifestyle, but the things that are repellent about criminality are right there in the foreground throughout the film.”

Beyond the iconic performances, dialogue, and memorable scenes, the soundtrack to Goodfellas is what makes the film stand out beyond the other films of the gangster genre. Inspired by Kenneth Anger’s 1964 experimental short, Scorpio Rising, Scorsese’s choices in musical selections date back to his first critically-acclaimed film, Mean Streets, with Robert De Niro walking into a bar with “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” blaring on the soundtrack. When I asked Kenny about why Scorsese found such joy in the musical selection process more than filmmaking, he explains, “I think that it’s the way that his mind works. The fact that he has always been really obsessed with music almost as much as he is with movies and his ability to tie particular pieces of music to particular environments, that comes from his life’s experience.”

The jukeboxes Scorsese heard from the bars and restaurants of Little Italy would play a significant role in how he shot the infamous sequence of Henry Hill, coked out his gourd, driving around trying to sell guns and drugs while being followed by helicopters as the music shifts from Harry Nilsson and The Rolling Stones to The Who, George Harrison, and Muddy Waters all in the course of ten minutes. Kenny explains, “It’s almost like composing a suite out of different rock n’ roll songs, but it’s also a suite in terms of its visuals, too. This is a self-contained scene that is images and music threading through to the final needle drop of no music, the gun to the head, and there’s no music in the rest of the film. That kind of conceptual perspicacity was, at this time, very particular to Scorsese. He’s maintained this practice of using pop and rock songs in his films, but I don’t think he’s ever done it with quite the level of genius that he does in Goodfellas.” The musical connection to Scorsese was evident in a 2007 Rolling Stone interview in which his Best Director Oscar for The Departed was placed on his mantle next to Robbie Robertson’s bronzed Fender Stratocaster used in The Last Waltz.

Kenny has interviewed Martin Scorsese before in Premiere and has sensed how the director is not a fan of flashbulbs or people chasing after him in his SUV, which is highlighted in The Aviator when Howard Hughes is accosted by cameras or in Raging Bull when Jake LaMotta is pummeled on the ropes by Sugar Ray Robinson and the flashbulbs from the stands. However, Scorsese’s work ethic remains at an obsessive pace since his days as a film student at NYU as he’s been planning to shoot Killers of the Flower Moon with Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio next year in Oklahoma, a far cry from his beloved New York City. “Scorsese’s gotten to the point,” Kenny explains, “where he feels that to make these films, and the Irishman is a large-scale movie, Flower Moon is going to be a large-scale movie; these are big movies on the scale of David Lean. In order to make them in a modicum of comfort and in order to get the results that he’s looking for, he needs this rather large budget in order to accomplish this. He is long past the point of putting a camera on his shoulder and going out into the streets.”

At this time, Kenny would have been planning to see the 30th Anniversary screening of Goodfellas at this month’s Venice Film Festival had COVID not affected international festival and theatrical screenings. As he pines for watching films at the Palazzo del Cinema on the Lungomare Marconi, Kenny seems optimistic for the film-going experience in the upcoming year: “Venice is a lovely festival in every way (laughs). I hope to go in 2021. You know, it’s grim to contemplate how long we won’t be able to do these things, but I do have confidence that there will be a time in the future that we will be able to do these things again. I’m happy to do them. In the meantime, you can stay home and read.” One book that is sure to be on every film lover’s bookshelves this fall is “Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas.”

Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas will be released on September 15, 2020.