James Marsh has been making movies for longer than you think. From his humble beginnings as a researcher for BBC, to his dark, experimental early days around the festival circuit with films like Wisconsin Death Trip and the under-seen, under-appreciated 2005 film The King (we talk about it a bit here, don’t worry), to his career resurgence as an Oscar-winning documentarian, Marsh is a veteran of both film and the deceiving industry that surrounds it.

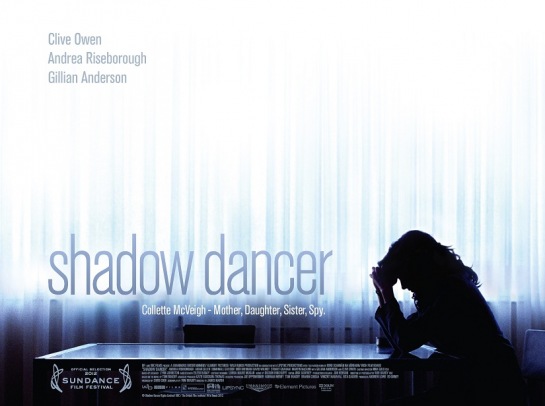

Here at Sundance with his new IRA thriller Shadow Dancer, starring Andrea Riseborough, Clive Owen and Aiden Gillen, the filmmaker took some time to sit down with TFS and talk about everything from the beheading of Gwyneth Paltrow, the ineviability of Transformers 7, finding a job after The King debacle and the feeling he’s still not a proper filmmaker, no matter what his Oscar says.

TFS: As a filmmaker, you are well-versed in both documentary and fiction? How is the approach similar and different?

James Marsh: The impulse is really the same, which is to tell a story as well as you can each time. You start with this blank canvas and your duty is to fill it with imagery that tells a story. That’s my simple mantra of filmmaking.

But the means of production are very different. A documentary is a much more free-form production. You can shoot little episodes and often make good on your mistakes. With a feature film you cannot. You get your one time – half of a morning for a scene let’s say – and it’s got to be done. So that’s much more unforgiving, but it’s much more exciting too.

With a feature, every morning you wake up and you’re anxious. You know you need to get through the day and knock it out, each day, for the next 5 or 6 weeks. So it’s a very different discipline and the rhythms of the work are different. The cutting room is much easier on a feature. If the script works and you’ve shot it reasonably well, it should come together and there’s only so much you can do with it.

On a documentary, you have almost endless possibilities. And your job is to chip away at the right part of it to get the thing that you want. So that kind of experience is very different on a documentary. It’s scarier and much longer.

Shadow Dancer is an IRA thriller, something that’s been done many times before. What made you think this story, this script, this cast, this time? What did you want to bring new to the genre?

I think that the two aspects that I responded to was that it felt different, perhaps even original, in that it’s set around the peace process – early 90s – it’s not the conventional, Falls Road Riot, all that. This is a kind of fresh perspective that dialogue is beginning to happen. You’re seeing that in the background of our story. And there’s a certain choice the characters need to make: do they move on and get involved in the peace process or do they become even more nihilistically violent?

That was what I thought was commendable about the script. That it was taking a piece of the conflict that I hadn’t quite seen worked out dramatically. I guess, more importantly than that, was the whole basic psychological premise. The idea of spying on your own family. We all love a story of someone being what they’re not. That was to me what brought me into the story, that extraordinary premise. What would that be like?

Now is there an intention here, in casting Clive Owen, to play with audiences expectations on what role the biggest star of the movie will play? Something like the way Steven Soderbergh talks about his actors in Contagion?

Oh yes indeed. [Clive]’s got that flawed heroic quality to him that people have used a lot in action movies. But he’s a very, very good actor. He made a movie called Croupier in the 90s that is really interesting.

And so that was what I was looking for out of Clive; that sort of nuanced, masculine vulnerability that he represents. You’re playing with expectations a bit when you’re putting any kind of movie star presence in your story. You want to subvert that as best you can. It’s good to destroy them. But we shouldn’t give anything away, we mustn’t. I believe it’s a film that relies on its final act left undisturbed.

Yes, but Contagion, I love [in Contagion] that Gwyneth Paltrow’s head gets cut off. What a sight to see! And good for her too for going for it.

This is a slow burn of a film, already getting comparisons to Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy…

Well that’s an easy one because that film’s just come out. And there are layers and layers of deception going on in both movies –

Now that film has been a success, both critically and financially. Does the success of a film like that give you hope? Hope that even if the big studios aren’t making movies like Tinker and Shadow Dancer people are still seeking them out?

I think it does actually. I do think people want to be challenged in that way of saying, ‘here’s a difficult plot. I’ll let it out for you carefully and precisely, with both the performances and the camera work.’ Those are the kind of films I like to see, and so perhaps that does gives us some hope that a film you have to pay attention to, to follow, like Tinker, Tailor – I’m not even sure now [about the ending], and I read the book. [Laughs]

But certainly the success suggests that…what happens every year is that there are smart and intelligent movies. There was a great article in GQ a while back about how Inception and how you’d hope that would make studios more open to original ideas, but no Transformers 7 is a much better bet then going with a director’s imaginative concept, like Inception.

So, sure, the studios don’t do that anymore. David Fincher does it. He’s navigated that system brilliantly. He subverts it, and he’s a filmmaker I really admire. But I would hope that if a film was positioned correctly you’re going to go, you’re going to pay attention. And I hope you’ll be rewarded with a satisfying and cathartic conclusion to this serpentine story.

What was the moment you realized you wanted to make films?

That came from a teenage feeling of sneaking out to see the sex and violence of movies. I wasn’t allowed to watch movies. It was forbidden in the house I grew up in. We didn’t have a televison. So it was sort of this taboo, imaginative thing. You go to a dark cinema and smoke cigarettes and grope girls there as well. And so it was a great forbidden fruit. And the power of what you would respond to.

Occasionally you would see something quite good. You’d see Suspiria, you’d see a Cronenbourg movie that was playing at your local flea pit. But mostly it was rubbish, and you’d go there to watch tits and blood. And I still do!

[Laughs]

There’s nothing better than a good B movie. There are so few of them around. But then you see something good and you want to get a piece of that yourself.

So I started working in television as a researcher for the BBC. And that’s such a hapless organization that in a few months I was directing bits and pieces for magazine shows and stuff, always with this fantasy of being a proper filmmaker. It sort of still feels that same way now.

What? You’ve got an Oscar!

Yes I do. That kind of felt like a fraud as well.

No!

…given the way they go.

[Laughs]

I was looking at your festival history, and The King premiered at Cannes, in Un Certain Regard –

Yes it did. Well, here’s the thing. You make a low budget film in the most difficult way. The King was a low, low budget movie. The film fell apart a couple of times as we made it. It was a real mess that film. It cost $1.8 million. And you make it, and there are so many of those out there, any given year. Hundreds.

And we’re at Cannes, Un Certain Regard. Amazing! I’ve arrived, this is the biggest, best film festival in the world. And we have our screening and it goes very well. There’s a standing ovation. Everyone loves William Hurt, everyone love Gael [Garcia Bernal], everyone loves me at the end of this thing.

And the next morning I wake up and I go and do some [publicity] stuff, high as kite, thinking ‘I’ve arrived. I’m a filmmaker.’ And I see a publicist hiding a cop of Variety behind her back. And I ask her ‘what’s that?’ and she says, ‘Oh you can’t read that! You can’t read that!’

And it’s the first review of the film. Check it out, Google it. It is the most horrible review you could imagine. Todd McCarthy hated the film, hated me for making it. And that set the tone for a certain response to that movie. And that’s when I realized the film wasn’t going to sell, it was going to be hated by a lot of Americans, which it was. So that very quickly became that little dream curdled. The film did get released and there is a small group of people who like it. Not many.

I do sense that it is a cruel and unforgiving film, and I wouldn’t make it now. I got that out of my system I guess.

But then after The King, no more Cannes. Sundance all the way.

Yeah, it’s weird. You come to it having made Wisconsin Death Trip, which was an archetypal, low-budget, experimental film in 1999. It actually went to Venice [Film Festival]. Sundance turned it down in fact. It went to Telluride and some nice festivals, but in my mid-career Sundance suddenly became where I’d been going. And Man on Wire was a brilliant experience here. Amazing. You come in with a low profile movie in the World Documentary section, and by the end of the festival the buzz is great.

Of course, after The King I couldn’t get a job. I was unemployable. So I went back to documentaries as a way of trying to make a living. So Man on Wire came along, great story, gift to a filmmaker. And I needed that gift, given where I was at, at the time.

And so do you keep coming back here out of a loyalty then?

I guess so. Actually, I think Sundance, at its very best, it is a brilliant documentary festival. They give equal billing to documentaries and they cherish there documentary films and filmmakers. Though I respect the narrative films, often the best films can be found in the documentary sections.

This is a place where [documentaries] can really flourish. So when Man on Wire did so well here, I was very happy to come back with Project Nim.

Jumping back to Shadow Dancer, Andrea [Riseborough] gives an amazing performance. Where did you see her and know-

I saw her in Never Let Me Go, a film that I had wanted to direct, of course, and didn’t get a chance to. Because of that, obviously I didn’t like it. As a rule.

[Laughs]

I saw something in that book I didn’t think the film delivered.

Can you elaborate?

The movie felt lifeless in all the wrong ways. It’s about different species of human beings that are created for a certain reason. I just felt there was so much tenderness and beauty in that story than I saw [on the screen]. I felt it was very sterile and I thought it was a conscious choice. And I’m not criticizing the director (Mark Romanek); I think he owned that story in his own way very well. It’s just that I had other ideas about the film and I loved the book and went after it and couldn’t get it.

But to answer your question, Andrea’s really exciting as an actress. She had something that was perfect for this story. She’s like a silent movie actress. You can do a close-up of her and so much is happening discreetly. There was one incarnation that wasn’t with Andrea, and once that didn’t happen Andrea was the person I passionately wanted.

I went to Berlin and I propositioned her. Literally, I said to her, ‘You’ve got to make this film. I don’t care what you’re doing. I don’t care about Madonna (who directed Riseborough in the upcoming W.E.).’ And, to her great credit, shall I say that she responsed to the script and it became a very beautiful collaboration with her.

What’s next?

I’m not sure. I’ve got two features I’m developing. One’s a supernatural story with Focus [Features]. A very unusual, very original supernatural story that I love. I’m writing the screenplay for that as we speak (an adaptation of Graham Joyce’s novel The Silent Land).

There’s another project in London called Valerio, which is the story of a playboy Italian bank roober. He pulled off the biggest heist in British criminal history. It’s all a true story; it’s a hapless tale of womaninzing Italian playboy who just manages to do this bank robbery.

It’s a very funny script. A much lighter script than I’ve done before.