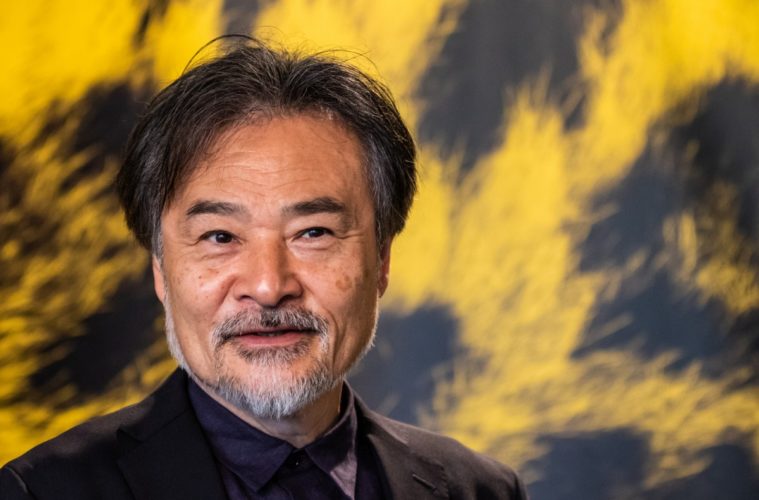

From the mezzanine level of Caffè Verbano, Locarno’s Piazza Grande glitters under the scorching sun, the army of black and yellow chairs sprawling below the festival’s biggest screen and iconic open-air theatre. At a table overlooking the piazza, Kiyoshi Kurosawa sits for the last few interviews ahead of the premiere of his new feature, To the Ends of the Earth.

It’s the Japanese horror master’s second time in Locarno–in 2013, his Real found a slot in the Swiss festival’s international competition–though the first in the non-competitive sidebar for which the fest is possibly best known for, the programme named after the square where, every night, an 8,000-strong audience enjoys some of the best in the year’s world cinema.

Assuming one can still find a leitmotiv in an oeuvre that’s as vast as it is growing increasingly protean, To the Ends of the Earth may not strike as your traditional Kurosawa film. Closer to his 2013 Seventh Code than to the works that earned him the title of J-horror master (Cure, 1997; Pulse, 2001) it is the second film the Kobe native shoots entirely outside Japan. Where the 2013 thriller had been filmed in Vladivostok, Russia, Ends takes place in Uzbekistan; here again, Kurosawa’s muse Atsuko Maeda serves as lead. Now with her third collaboration with the director–after Seventh Code and the cerebral sci-fi Before We Vanish (2017)–the singer-turned-actress plays Yoko, a TV reporter who travels with her crew across the steppes of Uzbekistan, ostensibly to film a 2-meter long fish that may or may not even exist.

A failed quest turns into an opportunity to grapple with an unresolved longing, a lingering and all-pervasive solitude. Thin in plot but not uneventful, free from jump scares but still perturbing, To the Ends of the Earth is a gentle-paced, melancholic ride, a frustrated tale of belonging graced by Maeda’s mercurial performance.

I took a seat in between Kurosawa and Locarno programmer-cum-interpreter Julian Ross, and spoke with the director about his latest feature, his horror master credentials, the fascination for Atsuko Maeda, mythical animals, and Edith Piaf.

The Film Stage: After Seventh Code, here’s another film shot a whole world away from your preferred turf, Tokyo. I was curious about your fascination for foreign lands.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa: Well, I always set out to make a different film, every time I begin a new one. I guess that’s just the kind of director I am. I am always drawn to new challenges, and to be able to work in different types of films feels like a dream to me. All that said, somehow I always end up shooting around Tokyo, the budget being the primary reason for that. Rarely do I get opportunities to shoot outside the city, let alone outside Japan. I never ask for those myself, but when I’m approached with a project such as To the Ends of the Earth, I am naturally drawn to it. There was Seventh Code, in Russia, and this one, in Uzbekistan. The producer came up to me and asked if I wanted to shoot a film there, and I said yes, thinking I’d be able to make another type of film if I were to do it over there.

I also read that part of your fascination with the country stemmed from your interest in the Timurid Empire, which comprised modern-day Uzbekistan.

Oh, I certainly do have an interest in that, but of course, that’s something beyond cinema. When I was young I was particularly interested in world history, and history outside of Japan, and I read plenty of books–and yes, I was particularly drawn to the rise and fall of the Timurid empire. Except–I’m embarrassed to say I didn’t know this from before–it was only when I was approached and asked to shoot in Uzbekistan that I came to the realization that the center of the empire stood on what is now the country itself. I guess it was some sort of destiny.

Going back to one of the points you raised earlier, the idea that you never really want to make the same film twice, I was wondering how you feel about being revered as a master of genre–J-horror, in your case. How comfortable do you feel with that label?

It doesn’t really make me feel uncomfortable. I have made several horror films, or at any rate, films that could be categorized as horror films, though it’s not like it was me who started the genre–and of course, I’ve also shot many other kinds of films, too. I guess it would be disconcerting if people thought horror films was all I did, and that I was just this expert on all things horror. I mean, I love horror films, and if there will be other opportunities in the future, I would love to work in horror again, because it is the kind of genre that offers many things, and many opportunities to explore.

A while ago, reading one of your statements before To the Ends of the Earth traveled to Locarno, I remember being intrigued by you describing its theme as “very personal” to you. How so?

I’m trying to recall in which context I said that, and what I meant by it. But sure, as far as the protagonist’s experience goes, the fact that she travels to another land and suffers from all sorts of small details, that’s something I’ve experienced myself too, anytime I’ve been invited to international film festivals. The experiences I went through form the basis on which I shaped the events in the film. I think a particularly representative scene is when Yoko sees a glimpse of Tokyo on fire broadcast on an Uzbek TV channel. I had a very similar experience myself, in March 2011, when that great earthquake struck Japan. I was in Paris, and I remember undergoing a similar experience as I watched Tokyo break down from afar on a television screen. That was how I was getting all my information. I was shocked–I kept calling people all over, but it turned out it wasn’t Tokyo on the screen, it was a town in the north east of Japan. And then of course, the big tsunami waves, and then the breakdown of the nuclear power plant. I have this memory of watching all these tragic events as they unfolded in Japan, but all from afar, and I feel the feeling is echoed in the film.

There are two near-mythical creatures Yoko and her TV crew are after. One is the “bramul,” this gigantic, two-meter long fish, and the other is the “markhor” described to us as a goat-like “beast with huge horns and long hair.” I use the word described because we never actually see the two animals, which dons them this sort of Beckettian aura. How did these two creatures come into the script? And how exactly do you imagine them?

I must confess this is the first time I’ve ever been asked this question (laughs). These two creatures, well, it’s not that they don’t exist–they do. Apparently the fish really does live in that lake we shot in [Aydar], and apparently it really can reach up to two meters in length. Same with the goat, the markhor: there are only a few hundreds of them now, they’re very much on the brink of extinction, and they’re so majestic they’re referred to as the “kings of goats.” And sure, as you said, we may not see them on the screen, but this the story of a TV crew that go out looking for them, and never find them. It’s a story about people traveling abroad, and people often travel with a certain goal in mind, but as far as I’m concerned, experience tells me those goals are never achieved the way you imagine they would. Things happen, things that go beyond your expectations, and that’s what special about traveling. At any rate, that’s been my experience in life, and that’s something reflected in the characters and their own struggles in the film.

There’s definitely a lot of irony in that depiction, of a TV crew’s failed quest, a satire of sorts.

Sure, but it wasn’t my intention to depict the TV crew in any ironic way. In a sense I go through the same they do in the film. I mean, they may go about shooting stuff for a TV programme, and I make films: like them, I have some goals and preconceptions in mind anytime I embark on a new project, but it’s always the case that I don’t achieve them. And I think in a sense this is the essence of filmmaking. These goals are rarely accomplished, but nevertheless there’s always something, something beyond your initial plans and expectations, that appears on screen, and that’s what makes cinema so special. These coincidences, serendipitous things, if you like. In a sense, what I wanted to depict was a TV crew going about doing their job, and that turned out to mirror my own work as a filmmaker, in that not everything I plan works out, much like in their own frustrated search.

After Seventh Code and Before We Vanish, this is your third collaboration with Atsuko Maeda. What is it that attracts you about her craft?

Simply put, she’s always left a great impression on me. Of course, there are many other great Japanese actresses out there, but she’s distinct, she has some qualities unique to her. Especially when she’s on her own on the screen, and she doesn’t share the shot with other people: she’s able to exist by herself. And as Yoko, despite having to face so many miscommunication issues with the local people, she pursues life, and pushes forward. As I began writing this role, I immediately thought of her.

Maeda is a renowned singer, which is the sort of career her Yoko wants to embark on. And while To the Ends of the Earth is certainly not a musical, music plays a crucial role here–most evidently in the two scenes where she bursts into a Japanese rendition of Edith Piaf’s classic, L’Hymne à l’Amour. Did you always envision music would play such a key role, or did the presence of actress and singer Maeda influence the decision?

I think it was both, really. There’s a scene we shot inside Tashkent’s Navoi Theatre–I really wanted to use this location, it’s so gorgeous, I wanted it to be in the film. I asked myself how I could fit it in the story, and I came up with the idea that the protagonist was pursuing a singing career, and there’s a moment in which she sort of hallucinates and imagines herself singing in that theatre. At the same time, I sensed Maeda would be perfect for the kind of scene I had in mind. So it was sort of simultaneous: on the one hand I wanted to exploit the setting, on the other I knew she was the best actress who could help me do so.

That choice of Edith Piaf’s piece was most interesting, it’s another foreign element in a story of alien things. Why that song?

To be honest, I really didn’t think too deeply about the question. In all fairness, I really just liked the song a lot, and thought it would suit Atsuko Maeda very much. I knew it’d be difficult for her, but I believed she could do it if she practiced hard enough. And of course, the other major factor was that as I started looking into the song I realized the copyright was free! (laughs) You know, when you use famous songs from relatively recent times you’re always bound to face copyright issues, but in this case, we overcame that obstacle fairly simply. As to why I included that scene in the end–well, this is a film that marks a departure from the idea of a genre, in the sense that, you know, when I make a horror film I want the audience to be scared, and therefore I use certain things such as scary music to instigate that. But this one here is an original story, and I wanted its interpretation to be completely free, and up to the audience to elaborate. In that sense, it’s fine for the audience to have different responses–to laugh, to be scared, and so on–which is why I didn’t want the music to dictate this or that feeling. But I did want to use music in the last scene. You can read the image anyway you want, but I wanted to ask the audience to just look at Maeda, at Yoko: all eyes on her. And one of the ways to ensure this would happen was to make the character sing a song–in this case, a whole song. And as beautiful as Uzbekistan’s mountains may be, my hope is that the audience won’t be able to take their eyes off her.

To the Ends of the Earth premiered at Locarno Film Festival and screens at TIFF and NYFF.