Leave it to Brian De Palma to turn one of the most traumatic events of his adolescence into a film school homework assignment.

Arguably the most personal entry in De Palma’s filmography, Home Movies began as a class project while he was teaching film production at his alma mater, Sarah Lawrence College. Fresh off the supernatural successes of Carrie and The Fury, he tasked his students with the challenge of creating a low-budget film using highly personal stories from his own teenage years. As De Palma bluntly states in the documentary De Palma, “99% of film students are going nowhere” after graduation. At least these students would get hands-on training and earn a feature film credit. More importantly, De Palma would get the opportunity to revisit his early days of guerilla filmmaking and indulge some of his usual obsessions (erotic surveillance, films within films) while poking fun at some of the successes and missteps on his early cinematic CV.

Home Movies begins with a hand-drawn animated credit sequence introducing us to the major characters, all thinly veiled cartoon facsimiles of De Palma’s own family. There’s the father, Dr. Byrd (Vincent Gardenia), a surgeon and serial philanderer. There’s Mrs. Byrd (Mary Davenport), the depressive wife obsessed with her husband’s infidelities. There’s the brother, Denis Byrd (De Palma stalwart Gerrit Graham), a self-absorbed cult leader. There’s his fiancé, Kristina (De Palma’s then-wife Nancy Allen), a loopy free spirit. Finally, there’s the younger brother, Denis Byrd (Keith Gordon as the surrogate De Palma), a shy voyeur who records everything with his 16mm camera. To quote De Palma on this coterie of extreme personalities: “I was living in a family of egotists.”

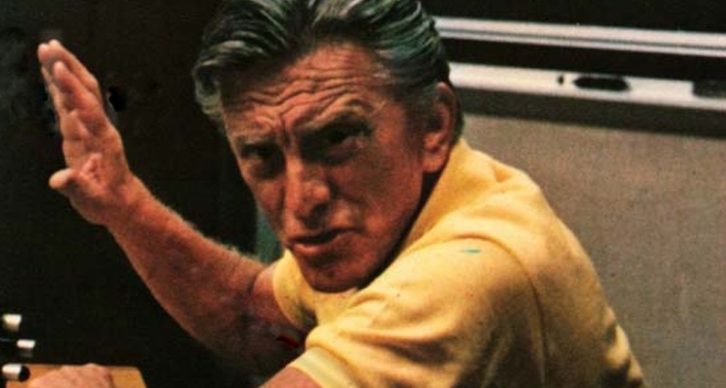

Post-credits, Home Movies quickly veers into metatextual waters, the instructional film-within-a-film that will provide a frame for the rest of this narrative. A professor simply referred to as The Maestro (Kirk Douglas, on loan from The Fury) is teaching a class on “Star Therapy.” Part Stanislavski, part Sigmund Freud, part Joseph Campbell, The Maestro acts as director, motivational speaker, and occasional psychologist, imploring his students to seize the starring role in their own lives. As his object lesson, he uses 16mm footage of the ineffectual Denis Byrd, a former student who has, by Denis’s voiceover admission, become “an extra in his own life.”

A smash cut later, and the film is now Denis’s story — the film-within-the-film-within-the-film. What follows is his film school self-portrait offered up to the audience as an extended family therapy session. It’s catharsis through farce, personal trauma mined for laughs, all of it deriving from De Palma’s outsourced family history. Scenes from James’s upcoming engagement are juxtaposed with sequences of his parents’ imploding marriage. Dr. Byrd gives adult James aggressive, slapstick physical exams that border on child abuse. Later, at their engagement announcement dinner, he luridly offers James’s new fiancé a free “private exam” as a wedding present.

Brother James is too self-involved to notice. He’s a health food nut who espouses a way of living called Spartanetics, a hypermasculine twist on Dianetics. He trains a group of impressionable young males (“Those Who Know”) in clean living and routinely interrogates Kristina about her numerous past boyfriends. He requires her to pass a rigorous pre-marriage “Temptation Marathon” during which she must resist sex, alcohol, smoking, and fast food. There’s an extended physical comedy scene where Graham crawls on the floor like a bloodhound and sniffs out the rogue scent of a greasy hamburger she ate earlier that day.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Byrd is making humorous suicide attempts with sleeping pills, despairing over her husband’s unabashed lechery. Hoping to catch him in the act, she enlists Denis in a peeping-tom mission. Though he’s busy swooning over his brother’s bride-to-be in windswept, slow-motion shots hinting at those De Palma would later bring to melodramatic perfection in Body Double, Denis begins to spy on his father with a 16mm film camera. He hides in a tree across from his office and dons shoe polish blackface so as not to be identified, a scene echoing De Palma’s similar usage of provocative racial iconography in Hi, Mom! Through his viewfinder, he catches his father cavorting with a nurse and breaks in on their lovemaking with the aid of cartoonishly bigoted cop.

Needless to say, this scene unfolds in a manner more Laurel and Hardy than the real life inciting incident. According to interviews, a young De Palma actually took photographs of his father and a nurse entering and leaving his office with a still camera. Later, he broke in through a window, confronted his father with a knife, and demanded to see where the nurse was hidden. That real-life anecdote reads more as a horror movie than Home Movies‘ slapstick treatment, and De Palma would revisit it again the same year in more typical Hitchcockian fashion with Dressed to Kill.

Eventually, Denis gets a chance to “become the star of his own life” when he follows Kristina to a biker’s bordello during her Temptation Marathon. When she refuses to have sex with one of the bikers, Denis bursts in and pulls her away from a potential date rape. Passive voyeur becomes active rescuer, a recurring motif De Palma mines later with similar peeper protagonists in Blow Out, Body Double and Femme Fatale. Because of Denis’ “heroic” act, Kristina finally sleeps with him — or so we presume. In an uncharacteristic display of restraint, De Palma allows their tryst to occur entirely off-screen. One can only assume this curious ellipsis has something to do with Home Movies being a school project.

But the film is by no means asexual, an aspect most evident in Home Movies’ potentially problematic rendering of Kristina’s character. Nancy Allen plays her as an agreeable eccentric and bears the brunt of this film’s absurdity. She’s had many lovers in her past, went “professional” at one point, and has a tortured history with a rabbit hand puppet named “Bunny” with whom she engaged in a live sex act. (A cheeky nod to De Palma’s own Get To Know Your Rabbit fiasco, perhaps.) She now uses the rabbit as a therapy doll / ventriloquist’s dummy and imbues it with an aggressive male personality. After Denis saves her from the biker bordello, Kristina gets blitzed on Mrs. Byrd’s sleeping pills and busts up her own engagement party, Bunny tossing out photographs from her showgirl past.

Once again, Denis plays would-be savior and rushes her to his father’s office to have her stomach pumped. Instead, Dr. Byrd uses her inebriated state as an opportunity for more lechery. Denis watches from afar, replaying the film’s earlier sexual surveillance scene, but with his own love interest now the subject. Kristina flees, only to have a gun-toting James appear and force her into the line of an oncoming car. She appears to die in a slow-motion car accident echoing a similar sequence played for suspense in The Fury. Only later do we learn that Kristina was hit (safely) by an ambulance.

Apart from recycling several of De Palma’s favorite thematic obsessions, Home Movies also finds him deploying a few of his preferred technical tricks. Despite the 16mm frame being a tight 1.33:1 squeeze, the film features at least two noticeable split-diopter shots. The sweeping Steadicam long-takes that would become the hallmark of De Palma’s later career are absent, but Home Movies does utilize undercranking for fast-motion comic effect, as in his earlier experimental movies. For fans of his big-budget blockbuster efforts, there’s also a self-destructing audiotape message that, in hindsight, plays like a pre-Mission: Impossible Easter egg.

When finally edited together at the end, the “home movies” Denis records throughout the film become something like the Byrd Family Zapruder reel, scenes of family celebrations intercut with surveillance footage exposing Dr. Byrd’s heinous sexual acts. The film ends with a horror movie sting à la Carrie, now played for laughs. A young girl comes across the tossed hand puppet Bunny beneath a tree. She picks it up, puts it on, and, in a throaty rasp, the rabbit offers to take her to Hollywood. Considering De Palma’s contentious, prodigious studio output that would come in the remainder of the ’80s, it may be a more ominous ending than a bloody hand reaching from a grave.

Continue reading our career-spanning retrospective, The Summer of De Palma, below.