Composer Nathan Johnson is a master at making off-beat and imperfect instruments sound distant yet accessible on a number of vastly different narratives (see: Brick, The Brothers Bloom, Looper). His latest work is a pair of scores for films that were both released this month, Jake Paltrow‘s neo-western Young Ones and the journalistic thriller Kill the Messenger starring Jeremy Renner. Johnson has also been producing a couple albums and helped coordinate the Mondo release of Looper on vinyl, so he’s has been pretty hard-pressed for any down time. We got a chance to talk with him about his recent projects and one can read the full conversation below.

The Film Stage: You’ve had quite a busy year. It’s interesting when films that composers worked on open concurrently, or on successive weekends. Let’s start by talking about Young Ones and your relationship with Jake Paltrow. That film premiered at Sundance at the beginning of the year, so when did you get involved with that project?

Nathan Johnson: I met Jake Paltrow fairly late in the process. He was working on VFX in Ireland, so we met on a Skype call and he explained what he was looking for in the score. He sent me the script, and I really liked it. I met with Jake the following week when he was in L.A. and I already had a hunch I wanted to do the movie after reading the script, but when I saw the rough cut, I was sold – I loved Jake’s story, his approach to it, the tone of it, everything. I was so into it that I came on board as an executive producer as well as the composer, and it has been really exciting to help bring this story to a wider audience. It’s a super slow-burn movie, with a beautiful visual style and storytelling approach, and I was into the ideas Jake had for the music as well.

Interesting that you read the script; a lot of times, I hear composers say they don’t even bother with it. They prefer to read the treatment because they don’t want to get bogged down with too many details ahead of seeing the footage. But was the film nearly finished by the time you started work?

Yeah, pretty much. They were still refining the cut a little bit but, by then, it was pretty dialed in. For me, reading the script is always my first request. It’s one of the things I care about the most and I find that it’s a really helpful thing. Aside from being an obvious starting point, it can help immerse me in the world. Then, when I see the cut of the movie I begin to understand something about the director, especially if it’s the first time I’ve worked with them. I also love seeing how they’ve translated what I read on the page to the screen.

There are so many things about the movie that floored me. First off, like you say, it’s a slow-burn narrative that comes across like Terrence Malick meets [your cousin] Rian Johnson. There’s a lot of purpose to all the slow shots, and also those impressive and highly inventive montages. But man, if I was in you shoes, I would have come aboard after seeing that extended funeral transition sequence!

Yeah, totally. I completely agree! The script was great, and actually, Jake just won Best Screenplay at the Sitges Film Festival in Spain. He was really great to work with and he’s got a really specific vision which is something that I’m always drawn to in the filmmakers that I want to work with. I’m less interested in working on things that could be confused with any number of authors, or, maybe a better way to say that would be that I really like working on projects that have a strong authorial voice to them.

What’s really smart about the story, and the direction and the way it’s presented, is that it’s sci-fi but it never lets the “science fiction” get in the way of the story. It’s very modern and you could almost see this playing out in small towns all across America. The issues with farms, crops, supplies and irrigation – it’s not so distant even though it’s set in the near future. There’s a lot of human interest and it’s because of the universal themes Paltrow presents. Did anything like that factor into your decision to use all those vintage and rustic sounding instruments?

Actually, I never come into a movie with a pre-conceived musical palette. That is always something that I explore with the director of each particular film and it’s really important for me that I’m not coming onto a project with too many locked-in ideas. I always want the palette to serve the vision that the director is going for, and I find it’s usually best if we can discover it together. So that was one of the early conversations and we talked more about concept. It made me excited to hear Jake commenting on the scores that he liked and he really wanted to create something that would have people whistling the themes as they walked out of the theater. [*laughs*]

Actually, I never come into a movie with a pre-conceived musical palette. That is always something that I explore with the director of each particular film and it’s really important for me that I’m not coming onto a project with too many locked-in ideas. I always want the palette to serve the vision that the director is going for, and I find it’s usually best if we can discover it together. So that was one of the early conversations and we talked more about concept. It made me excited to hear Jake commenting on the scores that he liked and he really wanted to create something that would have people whistling the themes as they walked out of the theater. [*laughs*]

You know, there are elements of atmospherics, but overall, he didn’t want tonal scoring. He wanted melodic themes that, in a way, call back to some of the classic film scores we all love. We began talking about the palette and what the sonic elements should feel like, especially because this film connects two different worlds; it feels slick and futuristic in some regards, but it also feels like it could have happened 100 years ago. So we decided to combine electronic instruments with wind-generated instruments (harmonica & harmonium) and a classical ensemble.

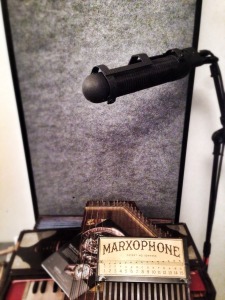

What is that instrument that sounds kind of like a tinny piano? It reminded me of something I heard in your score to Brick.

Yeah, what you’re talking about is an instrument called a Marxophone. We didn’t actually use that on Brick (though we used prepared piano, which has a similar sound in that score). The Marxophone is basically an old toy – essentially it’s an autoharp with spring-loaded hammers. When you press a key, this little lead mallet bounces down on the strings. It’s something that I’ve had for a long time and I love the imperfection of it – the bouncy, weird, slightly out of tune nature of it is so cool.

Yeah, what you’re talking about is an instrument called a Marxophone. We didn’t actually use that on Brick (though we used prepared piano, which has a similar sound in that score). The Marxophone is basically an old toy – essentially it’s an autoharp with spring-loaded hammers. When you press a key, this little lead mallet bounces down on the strings. It’s something that I’ve had for a long time and I love the imperfection of it – the bouncy, weird, slightly out of tune nature of it is so cool.

Jake and I would talk about classic westerns and, of course, we referenced Morricone a lot. He always used instruments in his westerns that you wouldn’t necessarily expect, and we wanted something that would have a similar strong central voice. The Marxophone became that element for all of the scenes between Michael Shannon and Kodi Smit-McPhee.

There’s an uneasiness to the film that has these young characters dealing with very mature responsibilities. Everything from tilling the land, to having a baby, the three “young ones” each have to become adults way sooner than they should have to. There’s lots of complicated issues but they are presented very subtly. I think that this film was tailor-made for your music and you nailed it.

Well I appreciate that. That was one of the reasons I felt so excited after I talked to Jake early on because I knew he wanted to push in that direction and, combined with how much I was into what he was doing with the film, I was really happy to be a part of the process. He was speaking to me in a very conceptual manner, and I love it when a director is able to talk about terms that aren’t even music-based. He kept talking about “the wind.”

Well I appreciate that. That was one of the reasons I felt so excited after I talked to Jake early on because I knew he wanted to push in that direction and, combined with how much I was into what he was doing with the film, I was really happy to be a part of the process. He was speaking to me in a very conceptual manner, and I love it when a director is able to talk about terms that aren’t even music-based. He kept talking about “the wind.”

It’s so great to talk in a storytelling modality rather than, “give me something happier here,” or “make it sound sadder here.” Jake was so inside of his story and he wanted wind to be such a big part of it. That is super helpful for me and sets me down a road to suggest something like, “What if we use harmonica, but in a way that it isn’t perfectly recorded?” What we did was close mic the harmonica so you hear just as much mouth blow as you do actual tone coming over the reeds.

It was the same deal with the harmonium, which is originally from India, and it worked in two ways. First, it’s not the kind of instrument I would plan to use on an American Western so that makes it very unexpected. The whole mechanics of it centers on a bellows you pump and that gives you an amazing breathy sound. Second, we actually got it from a vintage store so it was a little bit broken, and so there were certain notes that you would play and, depending on how quickly you moved the bellows, these high pitched fans emerged that sounded like a synthesizer. It’s just the air from the bellows going over these broken harmonium reeds, but it sounds like a robot. [*laughs*] But again, dealing with very conceptual stuff sets you in a certain type of sandbox with rules and restrictions that end up being really helpful for the story and sounds you’re trying to excavate.

Let’s get into a little bit of the score to Kill the Messenger. It takes place in the 90’s and your score definitely feels like it with all the guitar work. How did you first start working toward that sound?

The film is a classic journalism thriller in strong the vein of historical movies like All the President’s Men. It was a really fun project to work on. The director, Michael Cuesta, was editing and doing all the post-production in Manhattan and so my wife and I relocated to New York during the coldest part of the year for a couple months.

The film is a classic journalism thriller in strong the vein of historical movies like All the President’s Men. It was a really fun project to work on. The director, Michael Cuesta, was editing and doing all the post-production in Manhattan and so my wife and I relocated to New York during the coldest part of the year for a couple months.

Michael wanted the score to be slightly different from other electronic thriller scores – specifically, he was interested in evoking the personality of Gary Webb (played by Jeremy Renner). In the 90s, Gary was sort of a rock and roll journalist, and so we talked about the idea of using electric guitars as the basis and the driving point for the score. But we wanted to do it in a certain way that didn’t feel like…

…like a Whitesnake music video.

*laughs* Yeah exactly! We did not want this to be a purely rock and roll electric guitar score. It was important that it still felt pulsing and suspenseful… you know, really key to support the storytelling in that way, and so we developed the music using a lot of bowed electric guitars and live drums. My good friend Judson Crane has this instrument called a guitarviol which is a combination between a cello and the guitar – it’s fretted and you can plug it into an amp. So we were doing a lot of bowed guitar techniques that had us running that noise through pedals.

Then I built these synth elements from guitars combined with traditional synthesizers. And of course, it was really important to drive the story forward, so I brought in Darren King, one of my favorite live drummers. He’s notorious for duct taping his headphones around his head before each show, because he’s just such a volatile performer. But instead of giving him the drum kit that he’s used to, we went into a massive space with a bunch of huge taikos and surdos, and I said, “Okay, here’s your drum kit. Play this.”

I wanted his eclectic background, and I was interested in the approach he would bring using his technique on bigger cinematic drums that he wasn’t used to. So again, I like those conceptual doorways that let you pull elements from the main character’s personality and then see how we could apply those into that  supported a journalistic thriller movie.

supported a journalistic thriller movie.

Kill the Messenger has under an hour of music. It’s not wall-to-wall, and Michael specifically wanted a lot of the scenes to breathe, which I really appreciate. But then there are these moments that are built around a lot of different things happening, and there’s one sort of pivot point in the movie where we use a six minute piece of music. I like movies that operate in that way. It’s not wall-to-wall. But at the same time, you’re not writing fifty 30-60 second pieces of music either. I like those scenes where we have a little bit of time to stretch out and develop the sense of pace and the creative ethos.

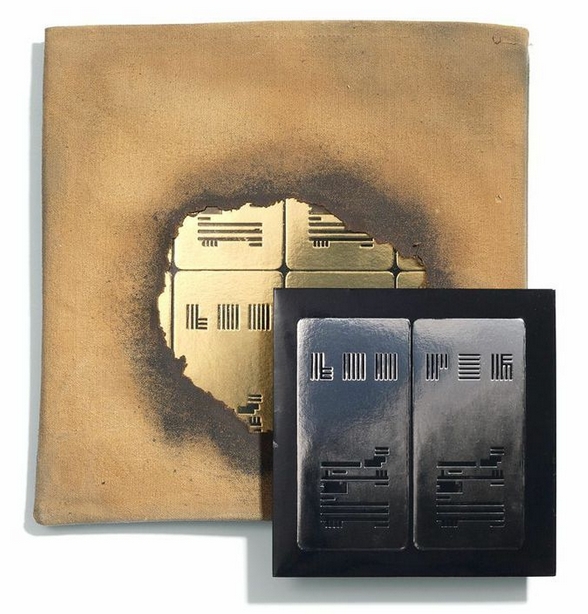

I’m a big Mondo fan and I follow their releases. So when I saw you put out the teaser announcement that the score for Looper was going to be released on vinyl, I told myself I had to get one. That and many other great LPs were released at MondoCon during Fantastic Fest this year and I’m so glad I got a copy. It’s a spectacular release, and I don’t know what I like better that burlap sack, or the gold plated gatefold. It’s amazing!

[*laughs*] I’m so glad you got one, because I knew they were going to go quickly. That was another really fun project to work on. Big props to Jay Shaw (the designer) on that. We spent a while talking and developing the idea. We were going back and forth on a lot of different options. But when he sent me that final concept I just flipped out. He said to me, “What if the cover was made of gold bars with the movie title in the gold bars? Then, what if we had a handmade burlap sack that had a blunderbuss whole blown out of it and you see the title through that?” I was so excited, but my first response was, “That sounds amazing…and it sounds impossible!” [*laughs*]

I feel so incredibly honored and excited. I feel like it is one of the coolest LP packaging designs that I’ve ever seen and am happy that it’s the packaging that gets to bring Looper to vinyl. Seriously, as cool as it is, I don’t know if Mondo made money at all on that release. [*laughs*] The amount of man hours that went into making that release has been totally insane!

I feel so incredibly honored and excited. I feel like it is one of the coolest LP packaging designs that I’ve ever seen and am happy that it’s the packaging that gets to bring Looper to vinyl. Seriously, as cool as it is, I don’t know if Mondo made money at all on that release. [*laughs*] The amount of man hours that went into making that release has been totally insane!

It was also really cool because they asked if I wanted to make some lock grooves which I was really excited about. The way records traditionally work is the groove that the needle follows just keeps spinning in towards the center, but a locked groove is something that doesn’t ever progress, so, in the middle of the record the normal groove leads into the locked groove and once it hits that, it just loops from there. It’s basically a drum break that will play forever, and we created it from elements in the score. I was also really glad to be able to include Kid Koala‘s track from the club scene on the 7 inch silver release. He’s my favorite turntable artist, so it’s fitting to feature him on the vinyl release.

Kill The Messenger and Young Ones are now in limited release. Listen to the former’s score above.