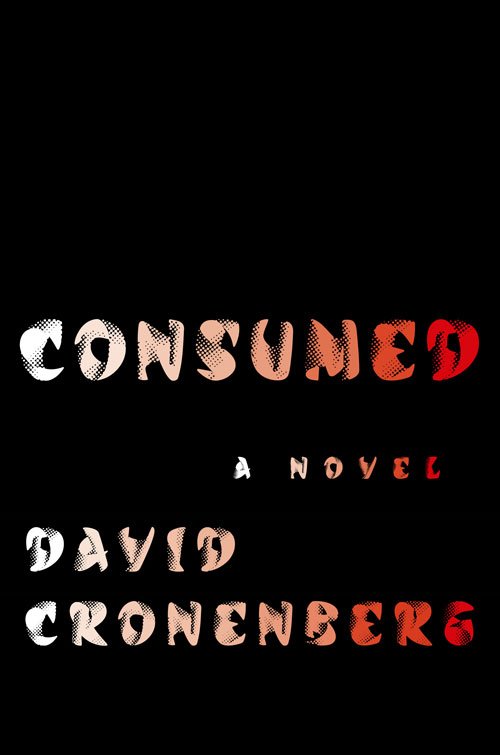

If David Cronenberg‘s acolytes are irate with the ever-shifting release strategy plaguing his latest film, they might take solace in knowing a different, more significant option is now available: Consumed, the filmmaker’s inaugural foray into literature. Although this release has been strangely underplayed, with only a recent short film and a couple of stray interviews promoting the occasion, cognizant parties have understandably high expectations. The notion of auteur becoming author is both a rare and curious enough event to warrant some drumming-up from Scribner, yet this auteur, in particular, stands right at the nexus point of the literature-cinema convergence. He has, after all, been deemed a “literary” filmmaker time and again — this title earned not only by an occasionally expressed preference for books over films, but screen adaptations that transpose William S. Burroughs, J.G. Ballard, and Don DeLillo with the utmost care — all while cinephiles across the planet revere his oeuvre for just how “cinematic” it is. How do the sensibilities of one so adept at visual communication — speaking for both the most extreme (bugs with talking-asshole backs) and subtle (razor-sharp contrasts in shot-reverse-shot dynamics) ends of the spectrum — conform to the page?

That those expecting a major work should keep most of their expectations tempered is not necessarily a warning against the text itself, but rather a comment on how we perceive Cronenberg’s work. As one who’s fairy set in preferring the “late Cronenberg” pictures over ickier, sleazier stylings inherent to most of his pre-Dead Ringers catalog, Consumed’s closer kinship with the earlier titles — narrative, thematic, and, to some extent, stylistic (consider passages in relation to images) components are much more in league with Videodrome than, say, Cosmopolis — can only bring with it a sense of artistic regression. One need not elaborate too fully on why that’s disappointing. This, however, is not to say we’re not looking at a failure: the book is about as pleasurable as it is breezy, thanks mostly to its easily processed prose — think closer to “airport thriller,” further from his professed literary heroes: Milan Kundera, Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, Burroughs, and Vladimir Nabokov — and, some major structural issues notwithstanding, a decent yarn practically engineered to earn the title of “page-turner.”

Earn that title it often does. Consumed’s narrative is split between Naomi and Nathan, “stylish and camera-obsessed” yellow photojournalists in search of lurid, fascinating stories that will earn hits for whatever outlet takes their latest report. (The occasional digs at Vice-like networks can hardly go unnoticed or unappreciated.) When a French-Marxist philosopher by the name of Aristide Arosteguy (side note: this book is a bit dumb) disappears soon after the murder and cannibalization of of his wife, Célestine, Naomi begins tracking the man’s whereabouts in Tokyo. Nathan, meanwhile, journeys to Toronto for the guidance of Barry Roiphe, a physician after whom a gonorrhea-like STD, recently contracted by Nathan, was named. (A disease that, it should be noted, was picked up from the patient of a shady Hungarian doctor from whose perspective we see in Cronenberg’s filmic companion piece, The Nest.) Both reach their desired subject, only to discover that obsessive, Internet-fueled investigations were hardly any primer for what’s truly going on, which is itself to say nothing of the particularly bizarre ways their assignments are connected.

Earn that title it often does. Consumed’s narrative is split between Naomi and Nathan, “stylish and camera-obsessed” yellow photojournalists in search of lurid, fascinating stories that will earn hits for whatever outlet takes their latest report. (The occasional digs at Vice-like networks can hardly go unnoticed or unappreciated.) When a French-Marxist philosopher by the name of Aristide Arosteguy (side note: this book is a bit dumb) disappears soon after the murder and cannibalization of of his wife, Célestine, Naomi begins tracking the man’s whereabouts in Tokyo. Nathan, meanwhile, journeys to Toronto for the guidance of Barry Roiphe, a physician after whom a gonorrhea-like STD, recently contracted by Nathan, was named. (A disease that, it should be noted, was picked up from the patient of a shady Hungarian doctor from whose perspective we see in Cronenberg’s filmic companion piece, The Nest.) Both reach their desired subject, only to discover that obsessive, Internet-fueled investigations were hardly any primer for what’s truly going on, which is itself to say nothing of the particularly bizarre ways their assignments are connected.

Here’s the thing: Consumed would still be trashy if Cronenberg had immaculately weaved these loosely connected narratives, in his alternating-by-chapter structure finding a justifiable way to ricochet from one side of the world to the next. He doesn’t, though, which leaves us with a juicy bit of 21st-century horror and some auteurist interest in how frequently these characters employ cell phones, tablets, and laptops while the narrator describes their screens as something of a separate physical space (Videodrome again). Yet the novel’s greatest fault is in its pretense to have illuminated much on the social-media age, with reams of sentences fumbling to make acceptable its tiresome “we’re all connected” theme. (At least a specific angle sometimes distracts from his tendency to stick an adverb into every other sentence.) If Cronenberg can hardly maintain a solid structure — sticking with Nathan’s storyline almost always feels obligatory, for one thing; he’s clearly more interested in Naomi and the philosopher — the social commentary might be best left by the wayside.

No matter how tired half this story may become and regardless of how flat its social commentary might prove, things begin to loosen up the deeper into this story we’re taken. Either through acknowledgement of or, more likely, forced surrender to what it ultimately is, I found myself embracing the book as its narrative escaped the confines of Toronto and Tokyo apartments, pulling back a curtain on the Cannes Film Festival (not that this shift makes much more sense with 200 pages of context) and, willingly or not, turning a bit dumber. If Consumed was created solely to allow the existence of a line that manages to reasonably cohere insects, a woman’s breast, and North Korean cinema, the effort was not a folly. (Ambivalent though I might be toward what sort of specter the nation eventually casts over this narrative — “North Korean nonsense,” I wrote in my notes — I’m also keen on a Burn After Reading-esque final scene, which gleefully leaves many threads hanging while providing the book’s biggest jolt.) When there’s the glut of lesser material to work through? You’ll wonder why this was the story Cronenberg decided to tell after decades of professing his love for literature, but that curiosity might also fuel worthwhile afterthoughts concerning the text itself.

Fellow admirers are thus bound to be fascinated by the experience, if not, like myself, also a smidge disheartened that our most overwhelming peek inside his creative process does little to affirm his genius. It’s fascinating to peek inside his perspectives on marital life and aging; of significantly less interest is his obsession in cataloging various camera models and lenses, which are discussed in some detail whenever (and this is often) someone picks up or shoots. I’ll take the mixed bag over nothing when going inside his head for an extended period of time, practically hearing the words in his own voice, and experiencing a story almost exactly as he must’ve felt is worth the price of admission. Barring the decent chance that this is his only foray into extended writing, there should be little hesitation in giving his next book a glance.

Consumed is now available from major book retailers.