Malignant forces within Catholic tales of evil generally seek to create Hell on Earth by finding a host willing to read the ancient words serving as their key. It’s therefore rare to receive scenes of demonic possession wherein a writhing body with black fluid spewing from its mouth screams for a portal not to be opened. But that’s exactly how writer/director Kimo Stamboel opens his cinematic adaptation of DreadOut—an indie survival horror video game from Indonesia. He introduces a group of men holding the demon down while also coercing a woman (Salvita Decorte’s Nancy) to read a phrase only she sees on a weathered piece of parchment. Her young daughter is held captive, the police are banging on the door, and we’re at a complete loss for comprehension.

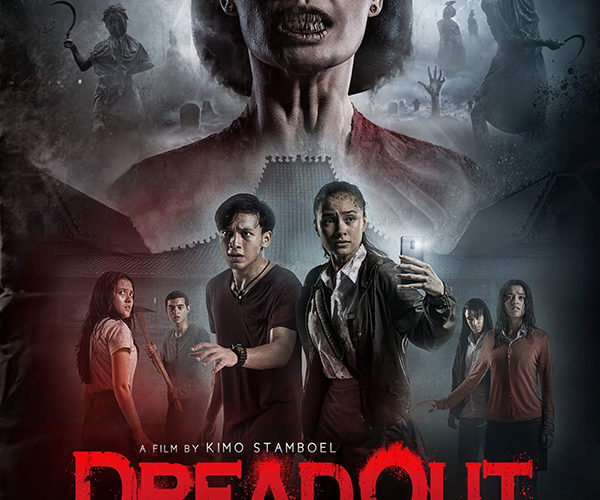

We fast-forward a few years to meet Linda (Caitlin Halderman) waking from a nightmare in Ms. Siska’s (Hannah Al Rashid) classroom. The fatigue of working double shifts on top of high school just to attempt raising the money she’ll need to afford college has her on-edge and in no position to do anything stupid enough to jeopardize that goal—unless a cute boy (Jefri Nichol’s Erik) talks to her unprovoked before his friend asks for a favor. While Jessica (Marsha Aruan), Beni (Irsyadillah), Dian (Susan Sameh), and Alex (Ciccio Manassero) have the money to bribe the guard (Mike Lucock’s Heri) of an old abandoned building they want to use as the site of a viral video, they need Linda’s familiarity with him to facilitate the transaction.

Stamboel doesn’t try to hide the fact that Linda is the little girl in the prologue and her nightmares repressed memories of terror. Rather than worry about whether something will transpire after this group of excitable teens cross through a hallway covered by police tape to unwittingly enter the room where it all happened, we’re left wondering what will. Because it’s not long before Linda picks up that same parchment her mother once held and sees those exact words despite everyone thinking she’s crazy. And without a firefight between cult members and the authorities to stop her, she speaks the passage aloud and watches as the three-pointed ouroboros beneath their feet opens up into a pool of water leading them towards a dangerously foreboding realm of the dead.

People familiar with the videogame are probably realizing now that the film goes way off-book plot-wise (if my cursory research into the source material is correct). Ms. Siska hasn’t taken her students on a field trip to an abandoned town and all the participants’ names have been changed save for Linda. Who she is and what she can do (it’s more than simply seeing words where no words are) appears to have remained intact as well as her discovering the best weapon for killing the zombie-like ghosts roaming this alternate underworld dimension: her phone’s camera flash. Whether it’s the light itself, the act of capturing them in photo, or wholly a product of this specific user, they shake in great pain before eventually perishing for good.

The ease in which this happens makes them okay for a quick scare and nothing else. They look sufficiently creepy with a random pit of their reaching arms proving to be a cool set piece, but they’re here more for additional dread than true conflict. For that we have a nameless woman in a red kebaya blouse/dress (Rima Melati Adams). This is her realm and she vows as its protector to ensure anyone who dares enter it stays for eternity. When one escapes, she must follow and bring them back by possessing the body of another to wield her telekinetic powers and inhuman strength. The goal then is to close the portal with her on her side and them on theirs. So everyone turns to Linda.

While this seems an obvious choice, Stamboel never enlightens us as to why. This might be discouraging to viewers who feel they’re running around in circles and taking everything on faith without context or purpose beyond “bad guy must die,” but fans of the game should feel right at home since players have been forced to hypothesize their own theories on message boards as to what’s happening since its 2013 release. The film’s two mid-credits sequences plant seeds for sequels that might help shed light on Linda’s powers and the mysterious cult’s desire to trespass in a dark world that’s content to be left alone, but as of now we have little more than the aesthetic to hold our interest when answers refuse to appear. Honestly? It’s enough.

I say this because DreadOut doesn’t tease answers before pulling back. It’s genuinely uninterested in giving them either as a product of not having any or a desire for mood and atmosphere to standalone. The prologue is less about providing a mythology than positioning its characters for future reveals that ultimately supply us even more questions. As a survival horror game this makes sense because we’re supposed to be caught up in present action. How does Linda and company escape their current predicament? How does the Red Kebaya Lady respond? Add a keris (an Indonesian dagger with a wavy blade) that may or may not be used to kill within her realm or our own and the whole film becomes an exotic treasure trove of darkly beautiful motifs.

You’ll need to suspend an ample amount of disbelief along the way, though. Linda doesn’t always use her phone’s flash by default and nobody else tries his/her own. The reveal that an ally might be an enemy who treats their friends as dispensable arrives without consequence. And the prevalent tonal severity evaporates with two out-of-place comedic moments from Heri at the very end. Because the film itself is indifferent to these incongruities, however, it’s not hard to blindly go along for the ride. The alternate realm’s production design seems steeped in Indonesian culture for an ornately attractive contrast to the abandoned building’s dilapidation and both the wirework and first-person electronic screen views lend some good frights. Hindsight may do DreadOut no favors, but it’s effective in the moment.

DreadOut is now playing the Fantasia International Film Festival.