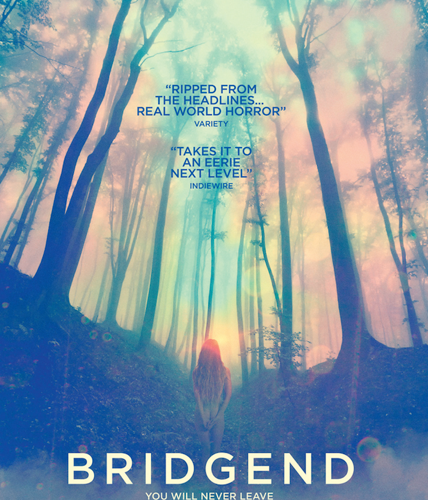

When 79 people between 2007 and 2012 commit suicide—many teens and most without a note—within a single town, there’s definitely a story to tell. Welcome to Bridgend, South Wales. No evidence has yet been found to link them together and some parents blame the media for reporting the tragedies in a way that glamorized them and perhaps inspired others to follow. It’s the kind of baffling and depressing mystery that conjures thoughts towards cults, the occult, and the supernatural. Anything to explain the nightmare is better than never knowing. So Danish documentarian Jeppe Rønde and his co-writers Torben Bech and Peter Asmussen attempt to do just that with his fiction debut. They place these layers of atmospheric dread and teenage angst above Bridgend and let its inhabitants wade through, lost and adrift until death provides escape.

Rather than hypothesize an answer or label it coincidence, Rønde’s path travels between. He injects working theories like a group of well-to-do kids lamenting boredom and absentee parents by wielding mortality as a weapon within a close-knit, private chat room community, applauding those strong enough to embrace that “better place.” Alongside this comes an implicit feeling of God’s judgment and a costly war against an evil hiding in the forest, touching all who pass with its melancholic finger of surrender. The townsfolk hope their local vicar (Adrian Rawlins) can save their souls just as they throw a cold shoulder towards the police for failing to put a stop to what must be a coordinated phenomenon. They all become withdrawn and emotionally erratic—laughing joyously one second before suddenly screaming a fallen comrade’s name into the sky.

This is the gray world we enter, paralleling the return to Bridgend from Bristol of Sara (Hannah Murray) and her police detective father Dave (Steven Waddington). She believes this homecoming will provide tranquility and time with her horse Snowy—the quiet life a good girl who listens to her father knows. There’s something about the “new girl,” though, that sparks interest in the local clique of quasi-ruffians drinking by the lake for a skinny dip or howling at the moon after vandalizing the neighborhood gas station. Laurel (Elinor Crawley) is the one who cajoles her into attending one of these bacchanalias lorded over by the haunted Thomas (Scott Arthur), Jamie (Josh O’Connor), and Danny (Aled Llyr Thomas). It doesn’t take long before the strangely feral woe that scares her becomes her own show of grief.

One friend falls. Then another. And another. The heavy drama lifts a veil of seeming happiness—or at least satisfaction—to reveal a hotbed of secrets not even Sara can avoid. Secrets involving her father, rituals of abuse that can make someone turn feelings of love on a dime either to protect his target or himself, and an adrenaline-junkie streak of rebellion to offset the obvious pain each fallen friend accumulates. As the tension amplifies so too does the visual disorientation to put us right in the middle of this psychological stress. Cuts back and forth through time arrive, the industrial score grows more powerful and disquieting, and we begin to question whether scenes hold living teens or the ghostly remains of yet more victims to the unknown awaiting his/her comrades to enter its dark waters of oblivion.

There’s a lot that I like about what Rønde has done here to create a mood piece that chills your bones as it crescendos into abstraction. Unfortunately he seems to have added too much for me to parse in a way that doesn’t also prove insanely frustrating. It may be that the first two-thirds is too long and leisurely steeped in a reality soon to drop away and make room for the surreally frenetic climax. I found myself getting comfortable in the machinations of a generic mystery wherein the cult of angst was real, thinking either Dave would break it up or Sara would at least save some would-be followers before it’s too late. So the abrupt change caught me off-guard—intentionally so, I wouldn’t doubt. But while the disorientation appealed to my senses, my brain felt annoyed.

To speak clearly on what exactly did this would be to ruin character revelations I’m still scratching my head as to whether or not I heard them correctly. For every gorgeously composed scene of naked flesh floating in the lake or once stationary trees crackling alive with fire after one man’s guilt and regret proves unbearable come uncomfortable moments of physical duress shrugged off with feign apology and weirdly unexplained circumstances that completely threw me for a loop as to comprehension. The acting is top-notch and each performance commits to the strangeness and fear crippling them from consistency or strength, but to what end I’m still unsure. I both love and hate this sense of being because while it’s definitely a testament to the filmmaker for making me feel as I do, I’m somehow still left underwhelmed.

The word incomplete comes to mind as if there was a way to complete a mystery that very well may never be solved—if a solution even exists. We’re told enough to get our thoughts moving that to leave empty-handed is a letdown despite my gut being full from viscerally reactive satisfaction. The two halves are too far apart to coexist as they do. Bridgend becomes two separate movies in my mind: one I enjoyed for its craft and mood and another that wowed me with its sure-handed unpredictability and deeply expressive emotion. It seems stupid to say, but both acts are too strong individually. More allusions to the chaotic end were necessary at the start so I didn’t invest myself in something Rønde cannot deliver. He was too good at making me believe he could.

Bridgend played at the Fantasia International Film Festival and opens on May 6th.