Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2025, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

Creating a year-end list engages with three distinct moments in time: you’re reflecting on the moment exactly a year earlier in which, full of blind optimism and hope, you anticipated the year to come. Then you’re reflecting on that actual previous year itself. (cue Expectations vs. Reality clip from (500) Days of Summer.) Lastly you’re looking ahead again with unfettered positivity in the forthcoming year.

Last year, I foresaw a 2025 driven by spectacle cinema. That wasn’t quite the case, for various reasons, most strongly indicated by my favorite film of 2025 being a 76-minute indie which takes place in one location with two actors. Now, I look ahead to 2026 and see that perhaps I was just a year early. This often happens in sports: a team trades for a superstar and everyone crowns them championship favorites right away, but in actuality it’s the following year in which they’re most positioned to win it all. So 2026 could be the actual year for the blockbuster. To my point, The Town podcast listeners will know that box office numbers could break $10 billion for the first time since 2019. A cursory slate glance reveals Chris Nolan’s The Odyssey and a summer Spielberg UFO film—as promising duo as any. While there will always be indies that capture my heart—from James Vaughan’s Friends and Strangers to India Donaldson’s Good One to Harmony Korine’s AGGRO DR1FT—each year brings the promise of a healthy mix of it all—the big and the small, the intimate and the dazzling.

Back to 2025, the inverse of the infamous Hamlet protest line rings true in that a general lack of discourse surrounding whether it’s been a good year or not means it certainly was. Many films I liked are absent from the below roundup, but thankfully make this publication’s master list. Some critics have posited it as more of a quantity year with a host of good titles with a lack of any truly great ones. I could entertain that thought, although my top three picks could compete in any year.

Honorable Mentions: Avatar: Fire and Ash – While mostly a beat-for-beat rehash of the superior Way of the Water, it’s aided by being the clear funniest of the three. Blue Moon – Caught this late and would likely be in my top 10 had I seen it earlier. Richard Linklater should collaborate with screenwriter Robert Kaplow more often. The Chair Company – Its inclusion is due to many critics putting Twin Peaks: The Return on their 2017 year-end lists. One of the truer Lynchian works in recent memory, I fell into a rhythm of watching new episodes on Sunday night and then again the following morning. Hamnet – A weirder movie than I expected from Chloé Zhao. One Battle After Another – Like Anora in that I loved it on a first watch and thought I’d be keen to rewatch but curiously haven’t… Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery – Rian Johnson’s Reddit-brained preoccupations in the still enjoyable Glass Onion take more of a backseat to something substantial: Faith.

10. 28 Years Later (Danny Boyle)

I caught this in the Dolby Atmos theater at the Landmark Sunset, and perhaps eager to show off their new wares, the sound was cranked too loud. Earsplitting experience aside, 28 Years Later is Alex Garland’s tightest screenplay yet featuring direction proving Boyle still has juice left. Sometimes the dumbest and most dated jumping off points (a zombie-infested Britain left for dead as a metaphor for Brexit) lead to inspiring art. I’m very excited for sequel The Bone Temple in a few weeks, which I hear from a studio friend who read the script is very violent and bleak.

9. After the Hunt (Luca Guadagnino)

I kept having encounters in L.A. where friends lean in and say, “It’s good, right?” puzzled at the film’s mixed-to-negative reception first in Venice and then at NYFF. I quickly confided that no, they’re not crazy. I too love how the film’s classical filmmaking melds with a nonsensical plot. I still can’t fathom that Guadagnino and team built all of Yale on a sound stage in London, after similarly recreating period Mexico City on a stage for Queer. I am curious if studios will continue to let Guadagnino spend so much money on these old school cinematic practices, but I hope they do.

8. No Other Choice (Park Chan Wook)

Not since Gore Verbinski’s A Cure for Wellness have I felt a director flexing this hard with the camerawork and editing. I prefer Park when he’s placing characters, who naively believe they’re good people despite behaving despicably, in unenviable positions. The capitalism themes are not overly complex, but sometimes cinema can be employed as blunt force object. Park is at his best when he leans into his nasty cynic side, which marries perfectly with his wicked sense of humor.

7. Marty Supreme (Josh Safdie)

Josh Safdie proves himself the heir apparent to Martin Scorsese, and like the best of Scorsese, Marty Supreme isn’t afraid to try things out, to be loose, a little messy. The unwieldy is undeniably alive. Once Tear for Fears kicks in amidst babies squealing in the film’s waning moments, I knew my post-breakup decision to buy and hold Team Josh stock was well placed.

6. Chronology of Water (Kristen Stewart)

Like the two films this reminded me of—Knight of Cups and Blonde–Kristen Stewart’s feature directorial debut takes time to settle into its rhythms. It was early during a punk-soundtracked montage in which Lidia Yuknavitch (Imogen Poots) leaves her repressive home and heads to college, quickly falling into a partying lifestyle, when I realized just how into this film I was—and just how impressive Olivia Neergaard-Holm’s editing is. It’s telling that even though I find Yuknavitch’s feminist poetry dated and cringe, it didn’t affect my experience of the narrative in the slightest. Stewart’s portrayal of Yuknavitch’s journey from sheltered teen to celebrated poet is enrapturing on its own terms.

5. The Love That Remains (Hlynur Pálmason)

A Pálmason film for those that don’t like Pálmason films, the Icelandic writer-director’s usual masculine angst makes way for something more joyful, although still pained. The film alternates between observations on messy familial dynamics or on the difficulties maintaining an art practice in a small town, alongside surreal touches in which a stuffed knight full of arrows comes to life, or a bully rooster grows in size to haunt the father who failed to kill him. Halfway through, I had the thought that Pálmason would be perfect to direct an imagined, mini-series adaptation of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle series. Someone should make that happen.

4. Eephus (Carson Lund)

Peanut butter and jelly, salt and potatoes, sadness and silliness—the latter a tried and true combination as any, and in Eephus, beneath the barrage of one-liners and oddball characters there’s exists a deep sadness, as it reflects on what we lose when our third spaces disappear. Eephus fans take note: many of the film’s collaborators reunited for Raccoon which just wrapped production a few months ago (read more at #69 on the list).

3. Eddington (Ari Aster)

I caught this twice on back-to-back Tuesdays at my favorite multiplex, the AMC Burbank 16, a dicey maneuver for a movie of this length. When I did this a few years back for Killers of the Flower Moon, that title felt long in the tooth on the second go-round. No such issues here. With Beau Is Afraid, Aster revealed his true skill of expert comedic timing and he flexes that muscle to great effect here. In Aster’s first three features, his camerawork felt showy for its own sake, but the addition of Darius Khondji as cinematographer brings a maturity to the camera placement and movement—while still showy, it feels motivated by narrative. A few years ago, The Sweet East elicited chuckles and raised eyebrows for its doofus ANTIFA subplot, but Eddington proves the real troll is to vindicate Facebook-scrolling Boomers’ worst fears by making ANTIFA both competent and well-funded. It is the savvier impulse. Laugh-out-loud funny, tense, expertly-directed and unafraid to take aim at everyone, Eddington is Aster’s first great film.

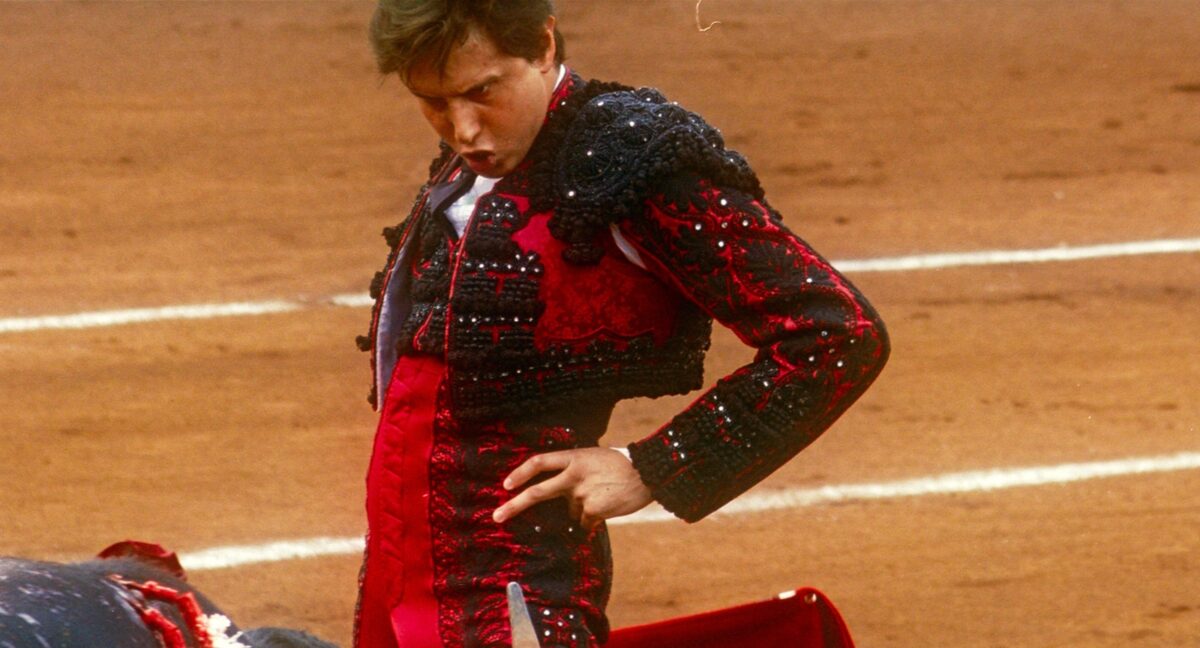

2. Afternoons of Solitude (Albert Serra)

Serra’s first documentary feature offers an intentionally locked-off look into the world of bullfighting. For instance, while lead subject Andrés Roca Rey might have a robust social life, partying after arena matches, we are forbidden a window into that aspect—should it even exist. Cheering arena fans are relegated to offscreen sound design, highlighting the isolation of both bull fighting and celebrity as a more abstract concept. We do get drives to and from the arena as Rey’s team heap praise on him, recycling uninspired metaphors which typically highlight the large size of his balls. Afternoons of Solitude is slyly constructed, utilizing repetition and withholding to build into something meaningful for audiences.

1. Peter Hujar’s Day (Ira Sachs)

It’s always a pleasure when the conceit of a film works against what you normally prefer. I’m no chamber drama guy. If two people are having a conversation in a room, I’d rather it be a play. Give me scope, give me locations and characters. So while Peter Hujar’s Day shouldn’t work for me, I found myself endlessly charmed by how cinematic and unplay-like it is. Ira Sachs and collaborators make a host of small decisions to expand the film, whether it’s the portrait photography interstitials, a rooftop smoke break, or a quick scene of Hujar (Ben Whishaw) and Linda Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall) dancing to a record. Curiously at 76 minutes, a trend has emerged of shorter features topping my year-end lists for this site. Perhaps I should prioritize growing my attention span in 2026.