It’s mid-July and I’m sitting in my living room, wondering what Ben Burtt, the sound designer behind some of the most beloved cultural artefacts of the 20th century, will think of the decor. Burtt was born in Jamestown, New York, in 1948. Like many of his contemporaries, his early days in the industry came at Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, but it was on Star Wars (1977) that Burtt made his name; with a tactile approach to foley work that led to the creation of many of the film’s most enduring sounds, including the hum of the lightsaber and Chewbacca’s roar.

In most cases, that would be enough to cement a legacy, but Burtt was only getting started. Around the same time, he challenged his colleagues to use a recording of a shrieking man in as many movies as they could—an in-joke that later became known as the Wilhelm Scream. Then, in the early ’80s, he began a collaboration with Steven Spielberg that resulted in the Indiana Jones films, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and three Academy Awards. J.J. Abrams would eventually call. So would Pixar. When we hear Wall-E talking now, that’s kind of Burtt talking. When Darth Vader breathes, that’s kind of him too.

Eventually, my laptop flickers and Burtt’s face emerges from the pixels—calling from the Locarno Film Festival, where he’s just received a lifetime achievement award. I start by thanking him for all his contributions to cinema—a genuine sentiment that briefly catches the modest veteran off-guard. In conversation, Burtt has a calm and delightful way of speaking, with a sense of humility that feels characteristic of his generation of below-the-line, Hollywood craftspeople—not to mention a handy skill for anyone frequently asked to recount a story they’ve told a gazillion times. For a lively half hour (edited here for clarity) we spoke about his early days in the industry, the things he still likes to hear and not hear at the movies, and the quest to record Abraham Lincoln’s pocket watch.

The Film Stage: I wanted to start by asking about one of your earliest films. I bought a DVD of Death Race 2000 when I was 14 and probably watched it 20 times. To later understand how influential it was, both for Roger Corman and you, was fascinating to me. How did you get involved in that? You must have been, what, 25 at the time?

Ben Burtt: I was just finishing my graduate work in University of Southern California film school and I wanted experience and needed a source of income. Another student and I found that we could get immediate employment as sound editors on very low-budget films being made in the backwaters of Hollywood. Richard Anderson, my friend, was cutting some sound at that time for New World Pictures, which was Roger Corman’s company, and they were doing Death Race, and they needed sound for those futuristic cars. They knew that I loved sound effects as a student, so they asked me to make up a library of exotic, crazy car sounds. The first things I made were for the trailer, which was being cut by Joe Dante, who became a famous director but at that time was a frantic, frazzled young man cutting film on a Moviola. I spent two weeks arranging sounds from airplanes and jet planes and other strange motors that I had in my collection. It was the first film I ever put sound into in Hollywood.

Did you stay in touch with Corman?

I actually didn’t meet Corman at that time. I knew who he was, of course, and like most students I’d grown up watching his low-budget exploitation movies. It was a few years later that I actually had a very nice meeting with him. It was after I’d done Star Wars, and I was traveling to New York and we ended up sitting next to each other on a flight. Of course I knew who he was and, strangely enough, he knew who I was. He congratulated me on the success I was having. Then I told him I’d worked on Death Race and he said, “Oh, yes, I guess that’s right. We loved those sounds.” It felt like a special endorsement having a compliment from Roger, because I admired his work. We all love the underdog filmmaker, the ones who can have a lot of limitations and still pull off something that was entertaining and had dramatic value.

Do people ever ask you to do the Wall-E voice?

Wall-E is really my voice effected electronically, so I can’t do it live. But the irony is that mothers will come up with their five-year-olds, usually a little girl, and the mom will say, “Do Wall-E for Ben,” and the little kid will go, “Wall-eeeee,” just perfectly. Why did they hire me? I don’t know. Humans are great impersonators––once we’ve heard something we can mimic a lot.

I wondered, after so long in your career, are there still moments when you’ll hear something in a film and think, “Wow, that’s cool,” or “that’s interesting,” or “that’s clever”?

Not that often anymore, but there are films that really stand out to me as having very interesting material. I still study as if I’m a film student. You learn to enjoy films on two levels: to be entertained or affected emotionally while at the same time running another input channel where you’re aware of the process––especially if it’s someone you know. I, of course, admire the work of Richard King, who did Master and Commander, the Peter Weir film, which I think is one of the most extraordinary sound jobs of all time. Because the ambience of the ship, the historical recreation of it, there’s so much detail. You can tell, with a film like that, that the filmmaker planned ahead of time and had the budget for the sound people to do their job, to take time to research all the types of sounds they might need to create a sailing ship.

A lot of those things are faked, of course, but I know that King went out into the desert with sails at the back of his truck to get the flapping and a little creaking. I greatly admire that. Of course, he did Oppenheimer more recently, which I thought was a very stark attempt to be hyper-realistic. None of the sound in that film glorified anything; it just seemed like they were giving you the facts. The films I’m known for, you’re magnifying everything, you’re exaggerating things, you are extending reality into surreal environments.

What about working on a project like Lincoln, say? Do you have a very different approach or does that come down to conversations you’ll have with the director?

Of course I’d worked with Spielberg on Indiana Jones and E.T., so I had a relationship with him, but I was very excited to have the opportunity to work on both Lincoln and Munich. I generally don’t get to do a film that’s quiet, where you get to have subtleties in the soundtrack, so it was kind of a new genre for me. Lincoln in particular: there are no battle scenes or monsters, certainly no robots. So I thought, “Wouldn’t it be challenging and fun to try to record things that Lincoln may have actually heard in his life?”

There are a number of good examples. Firstly his pocket watch. In the original script there were a couple of scenes that involved Lincoln and his watch alone together, using it as a kind of focal point for his meditation and thinking. The scene was greatly reduced in the final cut, but when I first read that I said, “We’ve got to record the real watch,” so I set out on a quest to find one. The Smithsonian in Washington had one locked up in a safe, and they were frightened to actually take it out and touch it, to wind it up, in case they broke it.

They eventually said “no,” but I found a second watch that came down through Lincoln’s family––from his son, Robert, which was in the Kentucky Historical Society. When I called the curator he was fortunately a Star Wars fan, and so he understood who I was and what I was asking for. So for the first time in 160 years, that watch was activated and we recorded it in their archive. We also had a clock in the movie that Lincoln had in his office at the time of the Emancipation Proclamation, which is still in the White House today. We got permission to go in there and very carefully, without touching it, record it ticking.

Wow.

And across the street from the White House, the bells of St. John’s Presbyterian Church, which are still the same. They even pointed out a wooden seat in the congregation where he sat, so we actually did some foley there, getting up and moving, which was creaking he might have heard. We went a little extreme on it. We found the buggy that was his and we did the doors on it and the leather suspension squeaking as it moved. Obviously we weren’t advertising the fact that these were authentic to the audience, but it gave us a sense of purpose creatively.

I really find that stuff kind of beautiful. Like on Titanic, Cameron having all the plates in the dining hall stamped with the White Star logo, even though we never see it.

Yeah, what does it matter? But it mattered to us. I think it matters to the creators. It injects something into the movie that’s hard to define.

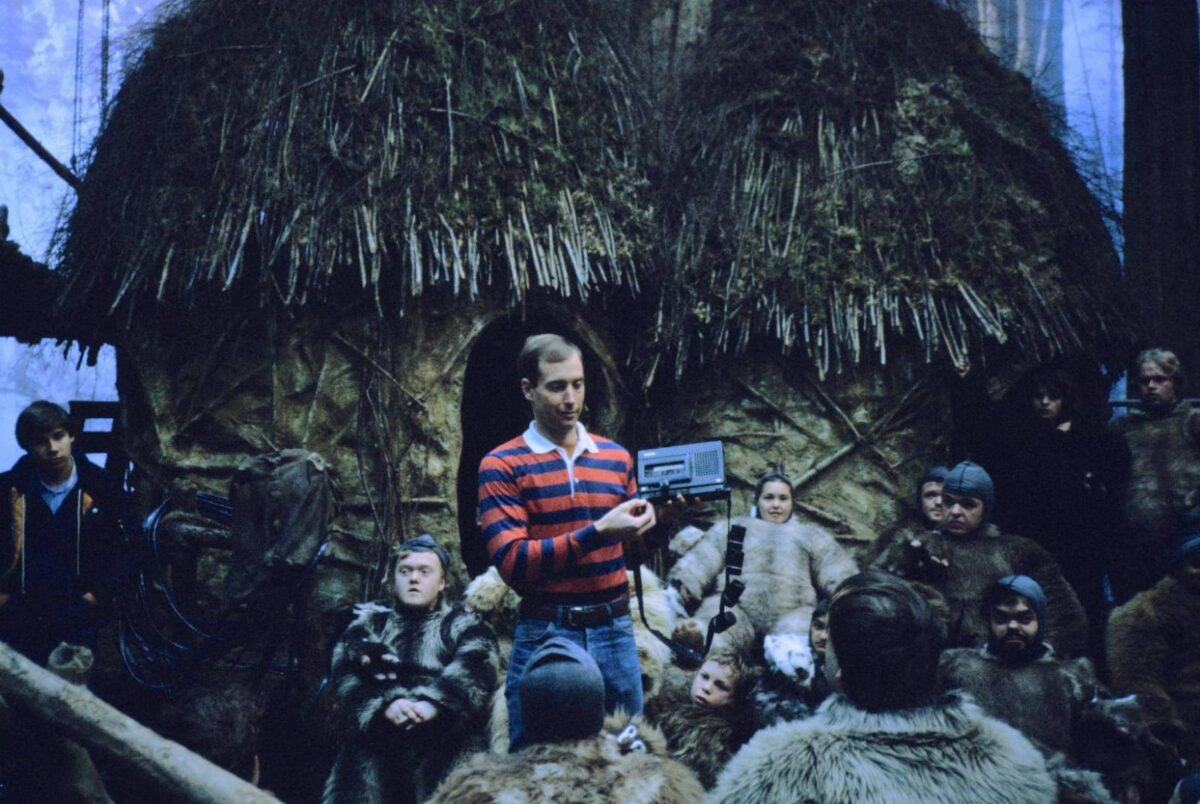

Ben Burtt on the set of Return of the Jedi

And on the other end of things, do you have any kind of pet peeves in terms of sound? For someone so hyper-sensitive to it, it must be like nails on a chalkboard sometimes.

[Laughs] You mean a really specific example? I’d hate to criticize peoples’ work.

No, of course. I don’t mean to call anyone out.

I would say what bothers me the most, in the general listening of films that I encounter, is the lack of sensitivity to the use of sound effects and music. That relationship. I love film music––we know the power the music has––but having music all the way through can devalue the music because the audience gets tired, because you’re using the same channel to reach them emotionally. Better films have areas of no music. I think that early filmmakers, the first that worked in synchronized movies, discovered that you needed to have a sensitivity to dynamic range. You had loud parts, soft parts, parts that were thin and simple, parts that were thick and full of sound. To me, the populist Hollywood films of today have lost that sensitivity. To make something seem louder in a movie, you have to precede it with something quiet, to have that contrast. Silence can be your friend. There’s been a few films that have done silence in recent times. The Zone of Interest.

That’s funny: I was actually going to ask you about it. It must have been interesting for you, when a film comes out like that and the sound is such a huge part of the conversation.

The idea of a film in which you’re using sound to stimulate the audience’s imagination, to let them complete the imagery, that’s a great idea. I had a tape recorder from a very early age, which was an unusual tool in the 1950s, and I would record movies off television and then listen to them back, no picture––just listening, over and over again, for entertainment. I was amazed at how the sound could stimulate imagery in my imagination, allowing me to generate a story in picture. That’s the great thing about sound: we have these experiences in our lives where we heard sounds and we connect them with our experience. It’s a real magic trick when you can capitalize on that relationship by having offscreen sound, or sound unseen, cause you’re adding visual dimensions to the movie. It’s a great approach, and every so often the subject matter of a film allows that sort of thing to happen.

I’m legally obliged to ask about the Wilhelm Scream.

[Laughs] Everyone’s obliged.

I remember reading about it a long time ago, so I tried to find the article. The first mention I could find was 2006, which I guess was around the time when people outside the industry started to know about it. There was the James Blake song…

Yes!

I’m just curious how it’s been, to see the life that it’s had, especially the last twenty years or so.

Yeah, 20 years! Well, to be honest, on some level I’m kind of embarrassed because it was a joke––an old sound effect which I heard in many movies as a child. It stuck in my mind because I thought it was amusing that it was used over and over again for different characters in westerns and science fiction movies in the 1950s and ’60s. So I eventually extracted a copy of it and put it in my student film. Then, in the time when I was working under Roger Corman––the Death Race era––I put it in a few kung fu movies. Someone would get kicked and they’d fly through the air and we’d put a Wilhelm in and get a big laugh.

It was a private joke between me and Richard Anderson, a student friend. Later we did Raiders of the Lost Ark together and shared an Oscar [for Last Crusade]. So for 25 years or so, Richard and I would put it in every film we worked on, as a kind of competition. I would sneak it into Indiana Jones and he would put it in Reservoir Dogs or something, and he would call me up and say, “Did you hear it, did you hear it?” It just went on like that anonymously. One of our friends, I won’t mention by name, knew that we were doing this and put the story on the Internet, and once that happened people were listening for it.

Ah, so it was a leaked thing?

It was leaked information. I don’t remember the exact chain of events but I had made a little documentary about it for in-house use at Lucasfilm, just to show among our editors and people. You make little behind-the-scenes things just to show at crew parties or something. I was testing out an invention George Lucas had called the Edit Droid, an early picture-editing system, and I needed something to cut, so I made a little documentary about the Wilhelm and that got a real laugh inside Lucasfilm. After that, the information got leaked out and there was no stopping it. A copy got into Peter Jackson’s hands and into Lord of the Rings. It got into commercials and all the Pixar movies. It was like a fire you couldn’t put out.

The other thing that you’re most often asked about is the lightsaber hum. I do really like the story, just the fact that one of the most iconic sounds in cinema comes from a projector. There’s something kind of poetic about that.

Yeah! I realize that: there’s something wonderfully ironic about it. That sound, just about anyone you meet knows it. It was probably the first sound I actually made for Star Wars because I had an immediate inspiration. I was a projectionist, so I knew that motor had a wonderful, sort of musical hum, so I recorded that right away. Shortly after, I recorded a buzz from the back of a TV set, where if you put a microphone really close to it it would induce an ugly buzz. You take the buzz and the hum, you mix them in a different ratio––a bit more buzz for Vader, a bit more hum for Ben Kenobi, about a quarter tone off from each other––just to distinguish them in the first fight. So yeah: when I made those I didn’t think I’d be talking about them 47 years later.

And here we are.

My goodness.