Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2024, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

The best film I saw in 2024, Alain Guiradie’s new masterpiece Misericordia, will sadly not be on the list you see below—such are the quirks of film distribution. Its distributors, Sideshow and Janus Films will release it next year. Thus, it must wait 12 months to occupy the top spot it richly deserves—which it will—barring a profusion of filmmaking genius in 2025.

Even so, the films that did reach U.S. screens in 2024 provided several highlights. An extraordinary, unprecedented occurrence was the sudden and rare elevation of Indian filmmaking to the most hallowed stages of world cinema. Payal Kapadia made history with All We Imagine As Light, the first Indian film to be selected in the Cannes Competition in 30 years. Perhaps its French origins helped, but Kapadia made the cut on merit, with her expansive, insightful portrait of a working-class, urban Mumbai. It took even me by surprise, and I grew up there!

Cannes maintained its supremacy over other festivals by premiering the year’s most notable movies, including a majority on the list below. Venice had some highlights, but otherwise, the fall season was lacking. The festival of my home city, the Toronto International Film Festival, offered but slim pickings.

The state of cinema is mostly healthy, a year after industry strikes took out Hollywood for nearly half a year. Arthouse cinema is still struggling to reach audiences, but gutsy, imaginative distributors have done a great job expanding access and adopting alternative channels to serve and grow the market. The sudden glut of releases in the last few months of the year remains a perennial problem. Films inevitably get lost in the jostle for awards attention. It’s a challenging balance to strike, though, as increasingly not just awards voters but critics show short memories and releases earlier in the year receive scant attention come year-end.

Even so, there is much to be thankful for, especially the great artists who work in this medium and edify us with their contributions. Without further ado—

Honorable Mentions (films ranked 11 through 22): The End, The Return, A Traveler’s Needs, Nosferatu, Emilia Perez, Eureka, Club Zero, The Bikeriders, Green Border, Music, A Different Man & Conclave.

10. Universal Language (Matthew Rankin)

A beautiful paean to Canada’s unyielding embrace of multiculturalism, Matthew Rankin’s absurdist comedy is set in an imagined Farsi-speaking Winnipeg. Over an eventful day, the lives of a dozen Iranian Canadians crisscross and intersect in a beautiful kaleidoscope of chance, connection and catharsis. Rankin gratifyingly bucks the trend of low-budget indies being directorially anonymous & formally unambitious. Rankin, in fact, cares immensely about staging and mise-en-scene and offers up a handsomely mounted production with compositions as elaborate and persnickety as a Wes Anderson film. What stays with you is the depth of feeling amidst all the deadpan humor.

9. The Settlers (Felipe Gálvez)

Felipe Gálvez’s western about crimes visited upon Indigenous people by white men—is a pricklier, more despairing Killers of the Flower Moon. Though The Settlers premiered concurrently with Martin Scorsese’s film at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, it has received scant attention. Not for want of quality, though—The Settlers paints a sobering portrait of ruinous colonialism and the Genocide of the Selk’nam people at the Southern tip of South America. Gálvez brutalizes the Chilean government, too, for its revisionist propaganda. In a nod to the genre, Gálvez offers one of the year’s spectacles with stunning landscape photography and rigorous, accomplished 4:3 framing and composition.

8. Nickel Boys (RaMell Ross)

RaMell Ross’ beautifully written adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s novel is vital because it is the rare American film that forces its audience to confront how it is directed. Far from delivering an anonymous, point-and-shoot film in his fiction debut, Ross opts for a rarely deployed formal gesture—filming in POV for the entire duration. The choice might be alienating for some, but there is no doubt a choice was made. The tale of the devastating abuse suffered by Black boys in a Florida reform school would be powerful in any format, but Ross’ daring brings such piercing insight that it becomes hard to shake off.

7. Asphalt City (Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire)

Asphalt City received such toxic reviews at its festival premiere that it had to change its name for its commercial release. It couldn’t shake off the stink, has slipped under the radar and has been lost to a fair assessment—all for the sin of premiering in the Cannes Competition. Knives were out for Sean Penn after his ghastly Competition bombs, even though he did not direct this film. Those giving it a chance will encounter a gutsy, visceral, cacophonous thriller about the PTSD first responders face and an outstanding leading man turn by Tye Sheridan. If only it had premiered in the midnight section at, say, TIFF, what might have been.

6. Queer (Luca Guadagnino)

Luca Guadagnino captured hearts and minds earlier in the year with his tennis drama Challengers but considerably improved upon it with this William Burroughs adaptation, his best film since I Am Love. It is unbearably poignant seeing literally James Bond, the paragon of masculine desirability, pining and wasting away over an amour that wouldn’t love him back. Sexual consummation isn’t even enough, as his lover’s soul remains out of reach even with psychedelic intervention. Daniel Craig is magnificently pathetic and empathetic in the performance of his life. And Drew Starkey makes for a suitably dashing foil who breaks his heart.

5. In Our Day (Hong Sangsoo)

Hong Sangsoo is prolific and given to genius beyond reason, but that means sometimes we must pick favorites. A Traveler’s Needs has found more favor this year, but In Our Day is no less a demonstration of his singular gifts and talents. A beautiful miniature with a double plot, to the extent his films can be said to have plots, In Our Day deals with admirers separately visiting a retired actress and an aging poet. Per Hong’s ascetic “late style,” the film has six speaking parts in two locations and takes place over a day and a few dozen shots. Hong’s ability to make the quotidian sublime is never not stunning.

4. Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (Phạm Thiên Ân)

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to put Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell alongside the most formidable debut films in history—Citizen Kane and 400 Blows. Phạm Thiên Ân’s film plays more like a career-capping magnum opus rather than a first feature—such is its formal achievement, unsparing rigor and stunning curiosity. Phạm Thiên Ân breaks all the established adages of filmmaking—he films on location, with animals and children and in complicated long takes with several extras. Making a 3-hour film in just 69 shots would itself be an achievement, but a bravura 25-minute tracking shot distinguishes it as one the best-directed films of the year.

3. All We Imagine as Light (Payal Kapadia)

My hometown compatriot and countrywoman Payal Kapadia deserves plaudits for accomplishing miracles—not limited to making one of the great city films in recent memory. That in her fiction debut, she’s made a film of extraordinary feeling and generosity would be enough to applaud her. Still, Kapadia is a legitimate pathbreaker, becoming the first Indian filmmaker to be selected in the Cannes Competition in 30 years. Her film’s existence & success is in itself an act of political defiance—in the face of a national cinema run over with misogynistic, regressive films—given to the hero-worship of male stars and masculine dominance and violence.

2. Vermiglio (Maura Delpero)

If Visconti ever made a working-class, historical, family epic, Vermgilio might be the result, though Maura Delpero carves her own path in only her second feature film. At just 2 hours, Vermiglio is modest in length and deals with a family of modest means. Still, Delpero’s ambition is evident in the novelistic sweep of her vision, taking in over a dozen main characters, storylines, and themes—all of which she expertly tackles. Above all, the singularity of her vision is richly seen in the elevation of women to the fore. They suffer, are bound by conventions, and are condescended to, but they also bloom, develop, and steer their own destinies.

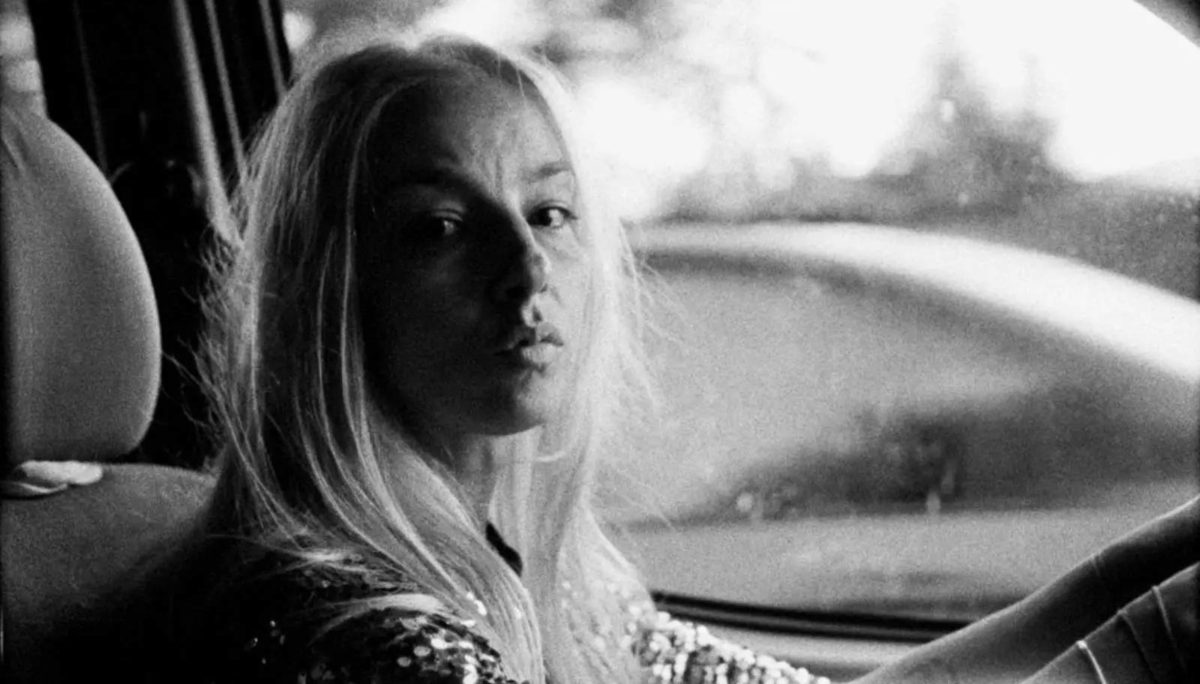

1. Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World (Radu Jude)

As rewarding an exactingly accomplished, formally rigorous vision can be, it is equally exciting to see a filmmaker who DGAF. Radu Jude, the enfant terrible of the Romanian new wave, never met a cliche he wouldn’t stomp on or social convention he wouldn’t puncture. His uproarious, profane and rule-breaking Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World is a Molotov cocktail hurled at everything that came before him. In a socio-political zeitgeist caught in the throes of burn-it-down populism, Jude seems to have his finger on the pulse of a restless populace. His tale of an overworked young woman captures the present moment like no other.