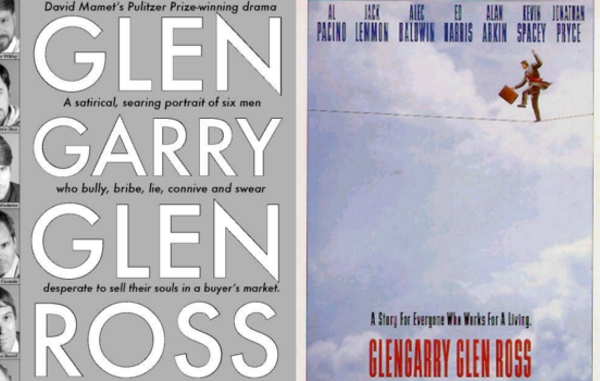

In 1984, playwright David Mamet received the Pulitzer Prize for his blistering play Glengarry Glen Ross, about a bunch of real estate salesmen at the end of their rope. In 1992, director James Foley achieved a small miracle: transforming what is essentially a long-talk piece into fluid, exciting cinema with his Mamet-scripted adaptation. The play is brutal… but the film does it better. In this age of corporate downsizing and buck-passing, as the national unemployment rate creeps ever higher, this vicious, profane and brilliantly-acted film is timelier than ever.

The spine is identical from stage to screen: a group of real estate salesmen turn on each other and themselves while scrambling to keep their jobs. Then, during the night, someone breaks into the office and steals the Glengarry leads, brand new sales leads coveted by the lower-tier men: George Aaronow (Alan Arkin) and Shelley “The Machine” Levene (the late, great Jack Lemmon). Ed Harris plays the loud-mouthed Dave Moss and Al Pacino is in pure slick-dick mode as cool, confident Ricky Roma. Add Kevin Spacey as office manager John Williamson – along with Jonathan Pryce as a nervous potential sale for Roma and an unnamed cop who appears in the third act – and that’s it.

The spine is identical from stage to screen: a group of real estate salesmen turn on each other and themselves while scrambling to keep their jobs. Then, during the night, someone breaks into the office and steals the Glengarry leads, brand new sales leads coveted by the lower-tier men: George Aaronow (Alan Arkin) and Shelley “The Machine” Levene (the late, great Jack Lemmon). Ed Harris plays the loud-mouthed Dave Moss and Al Pacino is in pure slick-dick mode as cool, confident Ricky Roma. Add Kevin Spacey as office manager John Williamson – along with Jonathan Pryce as a nervous potential sale for Roma and an unnamed cop who appears in the third act – and that’s it.

There are no women in this film, even though their presence is felt. But wives, daughters, girlfriends or even the “escort” Roma calls later to thank for the wonderful evening have no place in this world. Many women believe that all men are merely lost boys on one level or another. Watch this film again after reading the play and you’ll see what they mean.

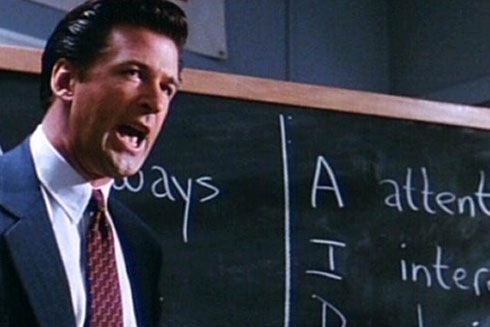

Adapting himself, Mamet doesn’t change much, instead re-structuring his plot, moving pivotal moments to where they should have been all along. His major addition is Alec Baldwin‘s now-celebrated role as the smooth-talking SOB “from downtown,” invited into the sales office once rainy night to motivate this ragged sales force will all the grace and subtlety of the Marine-training scenes from Full Metal Jacket.

Baldwin’s character – named Baker in the script – is Mr. Corporate himself. His speech is so powerful and has been quoted and referenced so many times, I probably don’t need to go over it. But I will. It has even been screened for animation students as a study in how posture and character design can denote an authority figure. Giovanni Ribisi‘s budding stockbroker is told to watch it for pointers in Boiler Room, and when Evan Handler‘s hard-luck Hollywood agent Charlie Runkel in Californication is reduced to slinging BMWs in the Valley, he’s told by his boss, “Always Be Closing,” since every asshole with a suit thinks they’re the only one who ever saw the movie.

Is Baker really as rich and powerful as he lets on? That question is at the heart of the film’s plot. Mamet loves his cons – his debut as a director was the dense, labyrinthine con man character study House of Games, which featured at least two levels of the confidence game. There are three different levels of con happening in Glengarry: the salesmen saying anything and everything to “get them to sign on the line which is dotted!”; the office manager – Spacey is perfection as the deadpan-asshole Williamson – who doles out worthless leads to the salesmen he wants to cut from the payroll; then there’s Baker. Early on in the pre-production of the film, Baldwin was to play Roma – then Pacino got involved and landed the role. Mamet then apparently wrote the role of Baker specifically for Baldwin, and what a great move it was. Baldwin may have trouble playing, say, a hard-nosed action hero (see the remake of The Getaway), but like Michael Douglas, he excels at playing men in positions of power. His famous monologue lays out the rules of this world: “A: Always, B: Be, C: Closing. Always be closing. Always be closing.” There truly is nothing else.

Director James Foley has always been more or less on the Hollywood sidelines – he excels with primal, alpha-male head-butting (At Close Range and After Dark, My Sweet) but unlike nearly every other film based on a play, Glengarry feels less stage-bound… which is strange, given that the film consists almost entirely of interiors. Foley loves his light-gels (watch Confidence and count the various colors he uses in his lighting), and for his world of salesmen, he limits the color palette to an array of reds (the Chinese restaurant where the men hang out, the neon outside) and blues (everywhere else).

The play appeared right in the middle of the go-go Reagan years, when big business, Wall Street and arms dealers were cleaning up. The movie appeared just one month before Bill Clinton was elected President of these United States – during both eras, a desperate silent majority was struggling to just get by. The play is still relevant and the movie even more so – Baker’s snarling little pep talk (“You think is abuse, you cocksucker? If you don’t like it, leave.”) echoes the rhetoric of such sensitive and compassionate right-wing personalities as, say, Bill O’Reilly:

dealers were cleaning up. The movie appeared just one month before Bill Clinton was elected President of these United States – during both eras, a desperate silent majority was struggling to just get by. The play is still relevant and the movie even more so – Baker’s snarling little pep talk (“You think is abuse, you cocksucker? If you don’t like it, leave.”) echoes the rhetoric of such sensitive and compassionate right-wing personalities as, say, Bill O’Reilly:

“[Y]ou gotta look people in the eye and tell ’em they’re irresponsible and lazy …. Because that’s what poverty is, ladies and gentlemen. In this country, you can succeed if you get educated and work hard. Period. Period.”

If you’re not making enough money, you’re not working hard enough. And if there’s no work? You’re not looking for work hard enough. And if you’re looking each and every day, all day? It’s still your fault. Read this brutal play – it’s essential reading for any playwright, and Mamet’s dialogue, with its breaks, stutters and natural speech patterns functions as a heightened form of language. The movie is essential viewing for anyone interested in just how they’re being conned. I have a friend who works as a video editor for a PR/”media support” company. In order to do his job, he needs updated equipment – in 2011, some of the multi-media machines in his office are still running the obsolete Windows XP and ancient software. The company will only update computers when they feel like – and for each new machine, another person disappears from the payroll… all while posting record profits in it’s “broadcast monitoring” operation last quarter.

Sure, Mamet has gone quite crazy and is now a frothing, right-wing ideologue. He’d probably agree with O’Reilly these days, and differ with my view of the film. That’s fine. When you’re getting screwed by someone, they should at least look you in the eye.

Have you read Mamet’s original play? What do you think of the film?