His Twitter account would indicate a man who, sadly, has retreated into a world of receiving royalty checks for remakes, watching basketball, and playing video games, but John Carpenter has, seemingly, accepted a certain status: some may say has-been, while, for others, it’ll be a (hopefully) more optimistic term along the lines of “underappreciated auteur.” Maybe it’s appropriate, however, that a man who snuck genuine pessimism into the multiplex time after time would, at this point, simply ramble to himself — finally institutionalized after years of too much “crazy talk.”

This very pessimism is never more apparent than with his “Apocalypse Trilogy,” in which the end of the world is a slow descent — no flames, wreckage, or dust-covered survivors, but the gradual loss of human experiences such as connection, belief, and culture. None of these films — The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness — were made consecutively (Carpenter happens to have produced classics such as Big Trouble in Little China and They Live between installments) and thus each represent different points of his career, presenting a worldview that only darkens, to the point that even each successive depiction of the apocalypse can be somehow grimmer than the prior. In the spirit of Halloween, we’ve set out to revisit the trio of films, which kicks off directly below with one of the most acclaimed entries into the genre.

The Thing (1982)

Next to only Halloween as his most widely-beloved film, The Thing sees John Carpenter at the beginning of his “studio director” phase, remaking a film ghost-directed by one of his great idols, Howard Hawks. Though the influence of Rio Bravo is clearly evidenced throughout Carpenter’s career (particularly with his repeated use of a siege conceit), their differing philosophies come easily apparent; Hawks often used genre as a loose playground for depictions of friendship, while Carpenter deals almost exclusively in doom, seeing horror as that which most accurately reflects evil. Thus, Carpenter’s version doesn’t see a central unit as some group of friends united through that classic Hawks terrain of professionalism, but, rather, almost always dispersed through paranoia, each worrying about the self and never the other.

Despite the film’s overwhelming demand to “trust no one,” it still needs a hero of sorts — the example, here, being MacReady, as played by Carpenter favorite: Kurt Russell. It was in their previous collaboration, Escape from New York, that Russell played his most iconic role, Snake Plissken, a protagonist who, behind those “badass” signifiers of a mullet and eye-patch, was a perpetual outsider, not riding into the sunset after saving the day but, instead, limping away from a minor anti-authoritarian triumph. This carries over to The Thing, his character’s introduction displaying the kind of guy not even able to take solace in recreation: pouring liquid on his game of computer chess — in comparison, the majority of his colleagues are never seen actually working, only in play — as hundreds upon hundreds of pool games have, inevitably, been played over an eternal winter, while others take to roller skates or, even, the radio. Although Russell’s tough guy charisma certainly makes MacReady easier to root for, he, as the point of audience identification, still seems ultimately indicative of Carpenter’s cynicism.

But once the threat is very apparent, the camera following MacReady running through the halls of their station to tend to the problem — without a second’s hesitation about accepting responsibility — it comes as the true articulation of his fear. His flamethrower-adorned leadership is operated through accusation and segregation, all in an effort to, again, save no one but himself — and, since this seemingly functional society didn’t need a leader before the alien, MacReady’s self-anointed hierarchy would, naturally, only lead to more distrust amongst the group.

Nevertheless, these are the people who, presumably, have to save the world; in fact, for all we see and know, they may be the only ones in it, what with their preceding Norwegian group having succumbed to suicide after failing to contain this same threat earlier on. In turn, their end is really our end, and its classic conclusion — the group now pared down to two men, the audience unsure of which is actually the titular thing, and the last thread of unity about to vanish into the cold Arctic air — is not only the ultimate example of a downbeat final note, but the confirmation of a dark inevitability.

Prince of Darkness (1987)

Made in response to a series of studio jobs he found creatively unfulfilling, the paradoxically religious and scientific horror film Prince of Darkness found Carpenter turning to a lower-budget project that granted him higher control. Of course, this entailed heady metaphysics treated not as subtextual material but, rather, text itself, even if accusations of headier themes being undermined by its blatant genre-play have been thrown about.

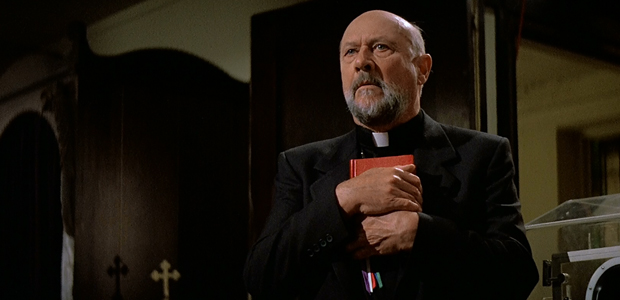

In the midst of an almost excessively long (though, still, incredibly menacing) opening credits sequence is the meeting of Prince‘s two age equivalents: head psychic professor Howard Birack (Victor Wong) and he solely referred to as Priest (a very hammy Donald Pleasence). Their instantly recognizable mutual respect is initially strange, considering their positions, but becomes easy to understand when realizing it’s over a shared fear of the end times, bringing us to the film’s admirably straight-faced conceit of the son of Satan being contained as a green liquid in a canister in the basement of a church.

In this case, the apocalypse prevention-unit primarily consists of physicists, leaving us to assume that intellect plays some greater part in their decision-making than, for instance, that of those gruff, blue-collar men who comprised The Thing‘s human element. Similarly, Prince of Darkness initially comes across as a far less “mature” or intelligent film than The Thing, chief amongst its criticisms being that its frequent grotesque violence is silly effects showmanship, and certainly not any kind that’s as impressive as Rob Bottin‘s work on the 1982 picture. But when one considers that the film is directly responding to the two basic institutions of reason, religion and science — the former but with definitive explanation, the latter but with a red-blooded fear of the unknown — it seems appropriate that the coldest of explanations is countered with projectile-vomited acid, flesh-stripped faces, and swarms of ants likely indebted to Un Chien Andalou. This dichotomy would even extend to Pleasence’s aforementioned overacting, his trembling coming across as wholly appropriate for any man of faith — especially when faith is, after all, often instilled through fear rather than love or kindness.

Still, Prince of Darkness’ most effective scares more often emerge through implication, including what are possibly the creepiest images in all of Carpenter’s oeuvre: the characters in their sleep haunted by a tachyon transmission from the year 1999, reminding us that “this is not a dream.” Both the end and evil itself are just a shape or brief, static-filled image, which is entirely appropriate for a film in which technology serves as the uniting force between science and religion. Scripture is now decoded on computer screens.

But, again, even with the entire world at stake, the film gradually shrinks in its locations, eventually to nothing but the church and the briefest flashes of the netherworld; the devil’s red claw reaches through at the conclusion, only to be sent back with a physicist’s sacrifice. But even this apparent victory over evil is only temporary, as the film’s final image — a hand reaching towards a mirror, into the netherworld — shows no lesson having been learned even briefly, instead very vividly faced the end. Carpenter positions humanity as essentially doomed to repeat its mistakes, for what makes both scientific and religious inquiries the constant they are is a need to explain — or, maybe, only reassure one’s self amidst the unknowable, untenable order of the universe. At least one answer to our question is provided: indeed, evil does exist.

In the Mouth of Madness (1995)

Of course the conclusion to this trilogy would come with the end of art itself — even if the “art,” in this case, is “that horror crap,” as Sam Neill’s insurance investigator, John Trent, would prefer to call it. His character’s been assigned by a publishing company to track down missing horror author Sutter Kane, whose work bears fewer resemblances to the young-couples-terrorized-by-supernatural-entity tropes of Stephen King than the existential terror of H.P. Lovecraft, to the point that it’s making its readers — ergo, most of the world — go mad.

Yet Trent’s initially disdainful attitude is not too far removed from Carpenter’s; the time between The Thing and In the Mouth of Madness (or even Escape from New York and Escape from L.A.) show an outsider’s melancholy transitioning to an outlook far more snide and, in frank terms, pissed-off. Being only a couple films away from his complete Hollywood exile — with critics and audiences having not been on his wavelength for at least a decade prior — In the Mouth of Madness sees Carpenter making a film where horror peaks to the point that, from now on, it can only repeat itself. Even the film’s central set-piece (the secluded small-town holding up Kane) begins to reveal itself as what is essentially a horror amusement park; while the rides all yield their temporary pleasures, they’re prone to either breaking down or overstaying their welcome.

This jibing tone is indicated from the get-go, via opening credits, as a cheesy electric guitar riff plays over shots of the supposedly evil horror novels being printed, instantly providing a different tempo from Carpenter’s incredibly familiar synth scores. Of course, one only makes the other more hopelessly uncool. Speaking to differences in aesthetics — and, in comparison to the far less aggressive, more “classical” early works of Halloween and The Thing — montage takes hold, and while maybe not to the same degree as the dissolve-crazy Carpenter of the last two Hollywood features, Vampires and Ghosts of Mars, it still manages to emphasize both shock and, more importantly, the dilution of shock through repetition, its gore effects and monsters only becoming increasingly ridiculous.

In further opposition to those last two films having an apocalypse be averted from one location, Madness positions the end as nothing but a complete given, no group, even in action, managing to work in prevention — the goal, if anything, is self-centered escape from the town, rather than salvation of the world. But amidst its anger, what ultimately separates In the Mouth of Madness from lesser (albeit still-worthy) meta-horror films such as Scream and The Cabin in the Woods is its understanding of the genre’s visual language — for one thing, never letting its point be drilled home entirely through references and self-satisfied comedy. Even at his most chiding, Carpenter remains perhaps the best genre craftsmen of his generation, making images that are good enough to warrant genuine inquiries.

Though, of course, Trent ends at a theater watching the very film we’ve just seen ourselves, initially laughing off the super-cut of its most ridiculous horror images — for which we, ourselves, could probably substitute any of the creature transformations from The Thing or tachyon transmissions found in Prince of Darkness. But laughter becomes a sob, one quickly robbed of any further catharsis by a cut to black and that damn opening guitar riff. How’s that for the end of the world, or cinema?