Destin Daniel Cretton’s adaptation of Jeannette Walls’ memoir The Glass Castle is more affected than affecting. It’s strange, given how Walls’ life story has all the makings of the naturalistic dramas Cretton clearly thinks he’s making; there’s poverty, negligent parents, alcoholism, a hint of sexual abuse, and children in peril, elements the director also explored in his break-out feature Short Term 12. In classic literature these would be topics Charles Dickens would’ve turned into ways in which to study humanity, in neorealism they would have served as examples of the moral decay prevalent even after the horrors of war, and in nonfiction filmmaking they would be mirrors we would rather look away from. In Cretton’s film however, they lie somewhere in between: he’s not Hollywood enough to commit to complete romanticizing or edgy enough to remove artifice and show us how dark we can become.

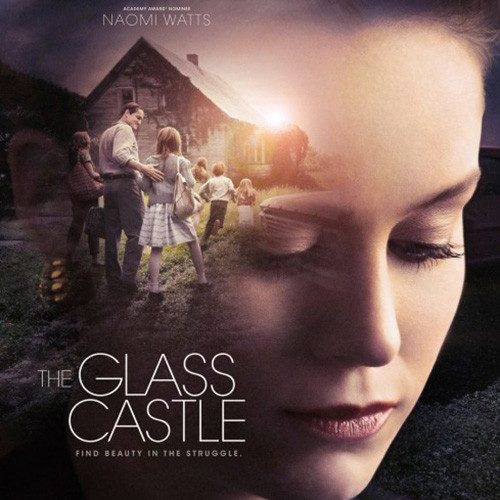

The Glass Castle shifts between tones, going from quirky coming-of-age story, to Lifetime-like biopic as it tells Walls’ story in two timelines. We first meet Walls in 1989 where she is played by a shoulder-padded Brie Larson, who sits at dinner with her wealthy accountant boyfriend David (Max Greenfield) as he brings her along to business dinners aware that her charm often helps him seal the deal with new clients. On the way home from dinner, Jeannette reminds David that she should be in charge of making up her own lies, and faster than you can say “foggy taxicab windowpane flashback” we’re in the late 60s, where Jeannette (played by the enchanting Chandler Head) is one of the youngest siblings in the Walls family, led by engineer Rex (Woody Harrelson), and artist Rose Mary (Naomi Watts), who asks her daughter to cook her own meal when she’s been struck by the muse.

After a failed cooking attempt leaves little Jeannette with a serious burn that would scar her for life, we realize her parents are less than qualified to be in charge of four children. Rex is an anti-establishment alcoholic who has the family move constantly as he keeps losing jobs, while Rose Mary simply allows him to lead the way, excited about the possibility of being the only artist in residence at whatever random town they happen to move to next. This leaves the children in charge of their own escape, and the film artlessly shows us how some episodes in Jeannette’s early life, had repercussions in her adult relationships.

It’s not difficult to understand why Jeannette has such a conflicting relationship with her parents. She knows she must love them at some level. Without this meaning she should excuse their poor behavior or try to justify them for how poorly they raised their kids. After all, no one is born knowing how to be a parent. But the film has a harder time achieving the balance between resentment and devotion, going instead from extreme to extreme. Rather than making Rex and Rose Mary seem like humans, it only knows how to make them be monsters or saints.

Harrelson and Watts do as best they can with the indecisiveness of the script, with the former throwing himself completely into the murky waters of Rex, and the latter choosing to show how Rose Mary must’ve made many heartbreaking compromises with her own dreams. The rest of the cast is serviceable, although Larson’s casting as the lead remains baffling because she’s never compelling enough for us to understand why her Jeannette is the protagonist of the story. The actress is at her best when she’s reacting to others, which is why in scenes where we’re meant to believe Jeannette is taking reins of her life, she comes off as unremarkable. It doesn’t help that the clunky editing highlights the feistiness of the actors who play younger Jeannette (Chandler Head and Ella Anderson) an element which is lost with Larson, who seems to be floating around in her head most of the time.

The Glass Castle never helps us understand why we should be invested in Jeannette, other than the fact that the credits informed us she is the star, which leads to another issue the film leaves unexplored: the bias that comes with authorship. Since the film is based on Walls’ memoir, it’s fair to assume her point of view influences every storytelling decision, but when the character onscreen is so passive, audience members might wonder why the story isn’t being told from the perspective of one of the other siblings, who seem to have led lives just as full and rich as the one we’re supposed to believe Jeannette led. The Glass Castle feels like the kind of star-driven biopic Jennifer Jones would’ve headlined in the late 40s, but when you’re lacking a magnetic star in the lead, and the screenplay is trying to decide whether it wants to be Dardenne or Disney, it’s nothing but a structure meant to shatter.

The Glass Castle is now in wide release.