Directed, written, produced by, and starring Nate Parker, the Nat Turner biopic The Birth of a Nation is an unflinching and hopeful call to action where the helmer’s passion can be felt in every frame. By nodding to D. W. Griffith’s controversial, formally groundbreaking 1915 film, Parker is forging a new cinematic history for one of America’s most shameful eras. What’s lacking in aesthetic cohesion, pacing, and subtlety is made up for in a powerful lead performance and an essential story with compelling religious undercurrents.

“Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep for ever” is the Thomas Jefferson quote that opens the film, immediately lighting the fuse for the rebellion against history’s gravest injustices. Fitting comfortably into the classical Hollywood biopic format, the story begins with Nathaniel “Nat” Turner as a young slave boy in 1809 in Southampton County, Virginia, where he witnesses prophetic visions that spur his desire for religious education.

He’s a slave to Samuel Turner (Armie Hammer), and their relationship is more interesting when compared with the exceedingly bigoted scum that occupy the majority of the area. While still exercising an unsettling amount of dominance, Samuel seems to understand Nat as a human, standing up for him when assaulted and buying Cherry (Aja Naomi King) for Nat to have as his wife.

A nearby, dishonorable pastor, recognizing Nat’s preaching skills, beckons Samuel to take him on a tour through the South, sharing God’s word with the most broken and destitute of slaves. As the Bible’s words are twisted to conform to the warped desires of the dominating race, Turner has a refute for each passage, showing precisely how God’s grace can defeat injustice — even if it’s not in his lifetime. These religious undertones, which become overt in the film’s final moments, give a divine resolution to Turner’s enduring legacy that the Confederate South wanted to wipe clean.

While he’s seen atrocities his entire life, it is Turner’s direct participation in this detestable cycle that causes the fire of rebellion to burn deep within his soul. Parker imbues Turner with a stoic fervor, contorting his impassioned expressions for justice and bringing a veritable presence to the frame. As a director, no punches are pulled in displaying the horrors of both the violence inflicted on slaves and, in turn, their cathartically vicious uprising over a few days in 1831. Teeth are smashed out by hammers, faces are bashed in, heads are cut off, and cavernous whip marks disfigure Turner’s back.

There are select scenes of remarkable cinematography, including the consummation of marriage figuratively displayed through candlelight and a shot beginning on the wings of a butterfly, fully transforming into something hideous. The film is photographed by Elliot Davis, and there’s a cheap-looking, washed-out aesthetic marking much of the rest of feature, which is punctuated by Turner’s unconvincing visions of a higher power. Perhaps under a more skilled director with a stronger sense of pacing and rhythm, the film would be even more effective. Henry Jackman‘s score is also too overbearing in sections, and is certainly not the last comparison to Braveheart this will warrant. But whereas Mel Gibson’s feature relied on staid machismo, The Birth of a Nation has a far more formidable message of repression permeating each scene.

In ending on a single, hopeful transition towards progress, Nate Parker’s debut is fiery cry to end the systemic injustice that still plagues our country and beyond. Too often we see films engineered plainly to launch a debate, and while The Birth of a Nation‘s heavy-handed, conventional approach may seem to fall into this category, there’s an instilled passion that will resonate long after the credits roll.

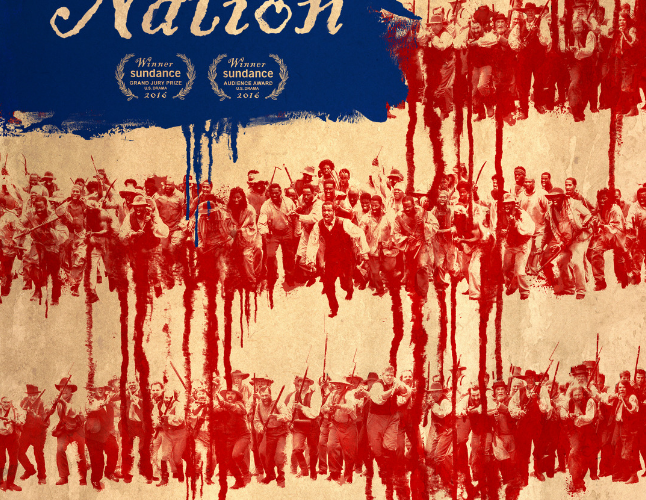

The Birth of a Nation premiered at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival and will be released by Fox Searchlight on October 7.