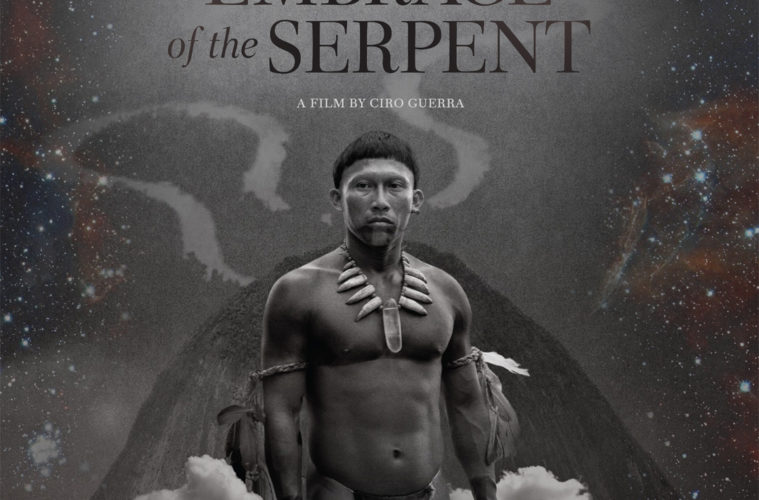

With its focus on the effects of exploration by white men on foreign lands, Ciro Guerra’s Oscar-nominated Embrace of the Serpent will inevitably be compared to Werner Herzog’s stories of savage nature, and while Guerra is investigating some of Herzog’s most well trodden themes, the chaos of man exists in the background, while the unspoiled sit front and center here.

Embrace of the Serpent centers on two explorers, separated by decades in time, searching for Yakruna – a fictional sacred plant with hallucinogenic qualities – but the movie is more about how outsiders – whether consciously or unconsciously – exert control. The repercussions of colonialism hover over the text even as these characters have “noble” intentions.

Loosely based on the adventures of real life explorers, Richard Evans Schultes and Theodor Koch-Grünberg, Theodor (Jan Bijvoet) and Evan (Brionne Davis) are men of science who do their best not to step on the toes of outside cultures. But at what point do they become gatekeepers by not expanding the natives’ knowledge? It’s a question continually posed and left unanswered.

The explorers are very much secondary to the character of Karamakate (Nilbio Torres and Antonio Bolívar), the last of his tribe, who still adheres to a strict set of rules of interaction with the jungle that range from a specific diet to ways of traveling through the space. After seeing decades of the culturing of his home and degrading rituals, Karamakate is wary of all white men, believing that their primary goal is the destruction of nature and other people.

But even he isn’t immune to the curiosity of white men who want to respect the jungle. When he meets Theodor, he’s reluctant to help, but nonetheless intrigued. This man is not only accompanied by a free Native American named Manduca (Yauenkü Migue), but has extensive knowledge of the Cohiuano Indians, a tribe that’s planted themselves on a neighboring riverbank.

Theodor is disarmingly warm, and yet also coldly intellectual, especially in a scene where he angrily tries to take back a compass from the Cohiuano Indians after worrying that they will replace their own view of cosmology with science learned from the compass. Bijvoet’s innate intensity brings an unexpected urgency to nearly every conversation, and makes these scenes consistently tense and breezy.

Evan, the modern-day counterpart, doesn’t have the same empathy and cultural openness. He’s more petty and he first tries to swindle Karmakate with a few dollar bills telling him he’ll be very rich. Kaiamakate sees through the ruse, and it’s not until Evan says that he’s never dreamt that Karmakate sees some kinship.

The aged Karmakate has also lost something. He can no longer remember his tribes’ rituals. He’s worried that he’s become a Chullachaqui, a hollow mirror image that’s lost in time, drifting without purpose, and a piece of folklore that’s the subject of multiple conversations in the movie about identity.

The two time periods are constantly in dialogue with each other in terms of Karamakate’s character, enriching the character from scene to scene. Where the younger Karamakate is still learning why he feels so defensive about his identity, the older Karamakate is consumed by the loneliness of being the last. Emotion is no longer a sign of weakness, but the only coping method.

Evan and Theodor are different in other ways as well; they’re very much the outlier in how they treat the people of the Amazon. They take them on their own terms, and stand in stark contrast to the countries previous experience with white men, which revolved around atrocities like slavery or the production of rubber. Even those who are now free are still haunted by the knowledge of that past and present. Like the characters of Claire Denis’ Chocolat, these sensations are a constant bottled ache that are waiting to be unleashed.

Embrace of the Serpent is far from airless though even when it’s fully engaging with the journey and its attendant philosophies. When staying with the Cohiuano tribe for instance, there’s an immense joy to watching Theodor dance with the tribe members, or see how Karamakate reacts with befuddlement to a phonograph, which he believes has captured his soul.

Karmakate fully believes in a more abstract, ancient way of living. In this sense, Guerra’s approach is reminiscent of an earthier version of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s singular aesthetic. That’s not to say that ghosts lie at the fringe of the frame as observers, but rather that history and lore is a fluidly visible sensation that courses through each frame, informing the overall journey. Dreams aren’t just a gateway into the spiritual world, they’re a compass for an equally surreal terrestrial place. The jungle is not a place to travel through, but a place to submit.

The movie doesn’t swear fealty to Karmakate’s viewpoint either. Guerra is just as likely to shine a light on Karmakate’s hypocrisies and his overreaching moral philosophies as it is to subtly lecture Theodor and Evan about their preconceptions.

Guerra’s camerawork throughout is deeply evocative as well, sinking into the endless quiet of the jungle and the contrasting chaos of its inhabitants with long tracking and dolly shots. If there’s a misstep, Guerra’s cutaways to actual animals in moments of spiritual transformation for the main characters feels strangely amateurish, and unnecessarily underlines dynamics that have already come through in other parts of the story.

Embrace of the Serpent feels special though because it doesn’t take a stance on the subject of science vs. spirituality, even as Karamakate’s character condemns science as the root of violence. Rather, it recognizes that the two subjects are deeply intertwined, even as they sometimes appear at war. Both subjects can be as unyielding or as elastic as you want them to be. It can be as slight as a feeling or as encompassing as a worldview.

Embrace of the Serpent premiered at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival and opens on February 17th.