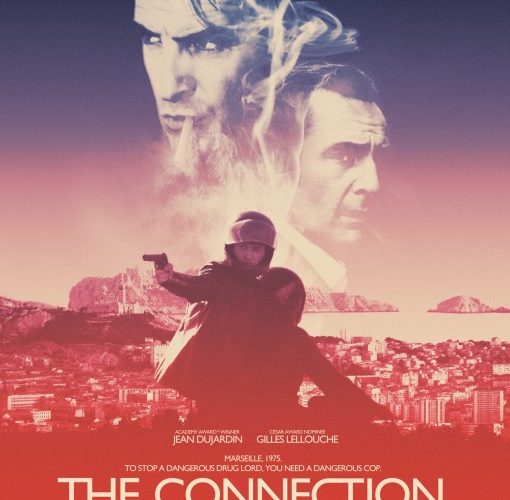

If the gritty, excruciating milieu of William Friedkin’s The French Connection triggered a new direction in the career of lead actor Gene Hackman, then Cédric Jimenez’s The Connection—an extrapolation of the international side of the same story—should also ignite new possibilities for its star, Jean Dujardin. Dujardin, mostly known abroad for his comedic work in the likes of Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist and the OSS 117 films, leaps to dramatic center in The Connection as Jiminez’s French Popeye Doyle stand-in, magistrate Pierre Michel, a tough law-enforcer trying to take-out the heroin trade running through Marseille in the 1970’s. Dujardin takes on a meaty role and gives it some multi-faceted depth that utilizes his capacity for charm and ability to confound audience expectations when it comes to character behavior.

Although it can’t—and doesn’t even try, really—to stand-up next to Friedkin’s Connection, Jiminez’s film excels at playing with expected genre conventions and crime story boilerplate to shrink a very wide, globe-trotting incident down to, essentially, a strategic game of cat and mouse. Although there are the expected jaunts into fabulous 70’s style and a muscular musical identity featuring a few rock montages, The Connection never coasts on the aesthetic textures; for a movie this entrenched in a back-stabbing, treacherous microcosm of drug trafficking and manipulative law enforcement, it’s strange to proclaim that the thing that works best is really the personal human element. Most of the plotting and set-up get tired very quickly, but there’s a spark running through Dujardin and his onscreen opponent, Gilles Lellouche, playing drug kingpin Gaetano Zampa, that occasionally sets the whole film ablaze, vibrating with a dramatic intensity.

Although Jiminez ultimately stumbles across typical cop-and-mobster tropes that have become the cinematic shorthand of Michael Mann and company, he does give The Connection enough of its own stylistic identity that we feel we are participating in an evolving story and not just a navel-gazing cinematic exercise. What works best is the way in which the director juxtaposes his two central characters and then confidently refreshes that stagnant conceit of the criminal and the enforcer sharing very similar lives regardless of their placement on either side of the law. Yes, we see that both are family men, and both must carefully navigate the treacherous world of their subordinates and associates, but beyond that we do get a mutual sense of them as men very carefully playing a game for an end that they hold dear. The various pieces on the board that orbit them may move in and out of focus, sometimes achieving or failing to achieve their part, but Jiminez ably evokes that for Michel and Zampa, everything is psychologically at stake.

Consider the way the film observes both men over the course of two decades, as they dance circles around one another. Dujardin is very effective at shifting Michel’s upright image slightly this way or that; demonstrating how far he’s willing to bend when necessary–forging documents and terrorizing lackeys is not beneath him–while also establishing those areas he’s fastidious at upholding–no bribes leads to a creative way of putting corruption to positive use– and those weaknesses turned resolve that help him do his job–he’s an ex-gambler who intimately knows the embrace of addiction. Playing these personal notes turn out to be a strength for the actor, who approaches each opportunity and situation with a similar sense of focus and immediacy.

The scenes between Michel and his wife, Jacqueline (Céline Sallette), tackle the usual cop-and-spouse discussions of overwork, alienation and potential danger, but there’s a gentle realism at play beneath that suggests that Michel is very much aware of what he could lose, and part of his better nature—almost tragically—is also realizing he’ll likely be asked to walk past a line that his wife and children cannot conscionably follow. Lellouche’s Zampa also has a wife who is sometimes at odds with his chosen profession, but his more compelling points of contention come from his array of underlings and partners who form an unending parade of exploitable possibilities; they’re either out for a piece of the empire, revenge, or not strong enough to weather the onslaught of Michel and his officers. Jiminez plays to Lellouche’s strengths when he sets up the improvisational calculation in Zampa’s retaliations to Michel’s efforts to crash his ring.

There are hints and echoes of a great movie in The Connection, but one can’t also help but feel that much of that great movie has already been made elsewhere. The familiar elements play out almost exactly as we expect and while Jiminez does take the time to explore the minutia of both sides of this conflict he loses something vital by relying so heavily on classic, established crime-film sensibilities. I found myself regarding The Connection in much the way I did the recent A Most Violent Year; both films unearth some fascinating characters only to lose them from time to time in a tapestry we’ve all but grown tired of looking at. Still, consider this a recommendation on the basis of Dujardin and Lellouche, and Jiminez too, that gives his audience some juicy things to consider in between the spray of bullets.

The Connection is now playing in limited release.