Though released nearly four decades ago, the impact of British director Alan Clarke’s stripped-down, visually matter-of-fact-yet-enrapturing “prison” drama Scum can still be felt in ripples throughout modern cinema, from the dirt-caked musings of the excellent Starred Up, to the philosophical discussion posed between a beaten Bobby Sands and stubborn priest in Steve McQueen’s Hunger. Shrouded in controversy upon its release, Scum has sat for years under the sort of “banned film” title that lends to a certain morbid fascination, which itself overlooks potential (or inherent) cinematic value. But Scum lives up to its title to this day, its manic energy balanced with an assured and naked openness that creates a searing level of realism and, as such, savagery.

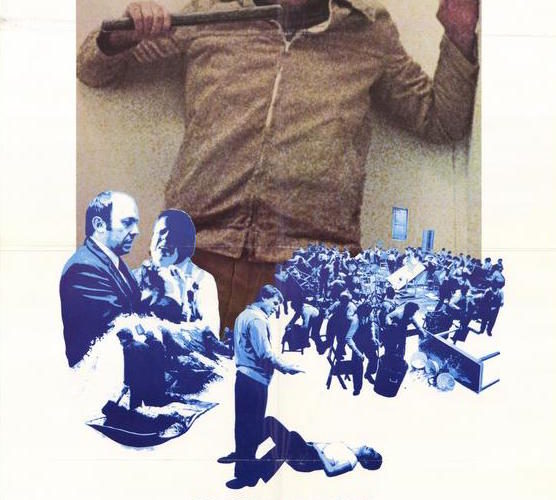

Scum is set in a juvenile-offender institution that is more akin to youthful hell than a chance at redemption for its sordid inmates, who struggle, fall, and brawl in the twisted political machinations set forth by both the inmates and the wards. While the narrative canvas stretches to many characters inside the walls — along with the filthy coal yards and industrial chambers of the institution’s grounds — we are brought into the world through the eyes of protagonist Carlin (a young, cheeky, and incredibly effective Ray Winstone), who’s been shipped in for a stint with two other young men. The institution’s hierarchical structure becomes immediately clear as the wards abuse Carlin and one young chap affirms himself as “daddy” to all the new blood. As the three adjust to a life with a free-for-all mentality that still adheres to a strict and brutal regime, bodies are beaten and power shifts as an undercurrent of manipulation from the higher-ups threatens to drive these lads mad.

Impressive is how Clarke and writer Roy Minton, throughout the film’s short runtime, balance the goings-on inside the institution. What’s traditionally the structural workings of an A, B, and C plots is replaced with a more complex weaving of many vignettes and almost episodic happenings that congeal in a mostly seamless construction. This is largely due to cinematographer Phil Meheux (who would go on years later to lens, among others, Casino Royale) and editor Michael Bradsell. Meheux handles the cold white walls with an incredibly deft hand, often relying on long static or tracking shots that still bubble with an energy and unpredictability, working perfectly in tandem with the firecracker performances. For a film that was said to feel too much like a documentary — part of its reason for making people so uncomfortable — Meheux’s stylings are loaded with confidence and careful planning. This is paired with the editing, which never intrudes upon character or camera in the name of style, yet allows the narrative to glide seamlessly between its many interwoven beats. Another stylistic choice that heightens the bare realism is a complete lack of non-diegetic music, whose impact cannot be understated.

Winston oozes a likability that is combated by his stifled anger — a struggle that gives way to pure, unfiltered aggression. Clarke allows the film to build nicely for its first third before unleashing a hail of violence that, formally, is treated in the same simplistic way as conversation, blending a line between untapped aggression and its inevitable outlets. This cohesion of style and substance makes a clear comment on the juvenile delinquent system of the ’70s with sledgehammer-force. At the same time, the undercurrent of violence runs so powerfully that when the pipe finally bursts, it is with such a ferocity as to leave the viewer wounded.

A review of Scum would be incomplete with a warning of the film’s violence and cruelty, which remains a disclaimer as honest and to-be-taken seriously as it did in 1979. In particular, there is instance of gang rape so brutal that it threatens a recommendation of the film to a wide audience. While its impact on the victim is studied — in the harshest and most depressing way imaginable — the act churns the gut with such realism that it leaves the viewer exhausted. This is, of course, how the act should be treated, but nevertheless hard to stomach. Yet what some of these reviews may fail to mention is a certain beating heart that’s nested into the fabric of Scum, often illustrated by Archie (Mick Ford) but also in the film’s insistence on treating its characters like human beings. Scrappy, brutal human beings, but lads with bleeding fists and bruised hearts nonetheless.

A new restoration of Scum opens on June 16 at Metrograph.