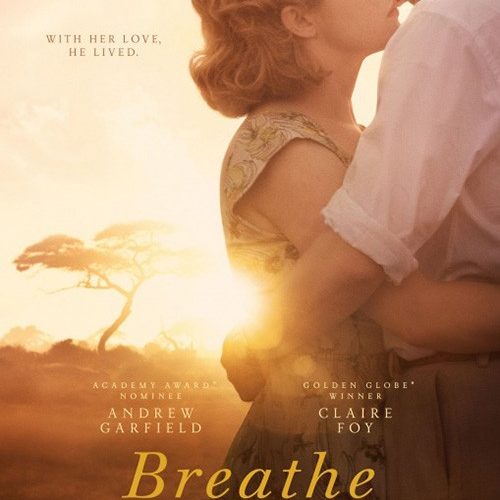

From its opening aerial shots, to the stylized font used to announce its title, it’s pretty clear that Andy Serkis’ Breathe is a throwback to a kind of movie Hollywood specialized in a very long time ago: the inspirational melodrama based on a true story that once would’ve starred Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon. Breathe stars Andrew Garfield and Claire Foy as Robin and Diana Cavendish, respectively, the married couple who revolutionized the way in which the world saw people with disabilities. When we first meet them in the late 1950s, Robin is a bright eyed young man ready to conquer the world. He sets his eye on the beautiful Diana at a cricket game, and despite his friends suggesting she would never go for a guy like him, within the first ten minutes of the film they get married, she’s expecting a child, and he’s started a tea-broking business in Kenya.

The golden couple capture the imagination of their friends and family, and their brightly lit life (courtesy of Robert Richardson’s stunning cinematography) seems destined for eternal bliss. Then suddenly, while in Kenya, Robin is diagnosed with polio which leaves him paralyzed from the neck down and with a life expectancy of just months. Refusing to listen to what the doctors have to say, Diana moves him back to England and focuses all her efforts on helping her husband not only find the will to stay alive, but also challenge the way in which people treat those with disabilities. Breathe will undoubtedly be compared to The Theory of Everything, in which another real-life couple, played by Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones, go through unsurmountable challenges and eventually manage to prove the entire world wrong.

The difference is that unlike in Theory, where we see Stephen Hawking leave his wife after she took care of him for years, the characters in Breathe are of a more saintly variety. The reason might be that the producer is none other than Jonathan Cavendish, Robin and Diana’s only child who also commissioned the script from William Nicholson. The result of having a proud son make a film about his parents, is that they are painted as a couple with absolutely no conflicts. Diana is as devoted as Robin is inspiring. The couple are practically robbed of any marital disagreements, and even if their sex life was clearly affected due to Robin’s condition, they become a strangely asexual couple, the likes of which Garson and Pidgeon would have been playing in the 1940s.

We only see the Cavendish marriage as a beacon of hope. Most of the plot focuses on how Robin, along with his friend Teddy Hall (played by Hugh Bonneville) developed a wheelchair with an attached respirator that for the first time allowed patients with severe disabilities to leave hospitals and become members of society. The invention of the impressive wheelchair might have been better suited for a Popular Mechanics feature or a Discovery Channel documentary, since it doesn’t make for exciting drama.

Turn after turn the film is unabashedly old school, with gold hue flashbacks and vignettes that lionize Robin more than they advance the plot. Garfield gives a satisfying performance, although one wonders why he makes Robin grin so much, while Foy is commendable for her attempt at spicing up her supporting wife role. Given that she is given much less to do in terms of physical challenges than her co-star (she only gets to appear in old age makeup), her performance shines in little moments where we get glimpses of Diana’s rich inner life. It’s a shame the film spends so much time denying her the imperfections that would’ve undeniably made her more interesting to watch.

Breathe is now in limited release.