The first image of Jafar Panahi’s Taxi, a POV shot looking out through a car’s windshield, immediately calls to mind the opening of his previous film, Closed Curtain. The latter also began with a shot from behind a window, though there, the view of the outside was partly obstructed by the window’s security bars. This revision signals a shift of tone for the director. While Closed Curtain represented a howl of despair at his situation – living in an authoritarian state that banned him from exercising his profession for 20 years without permission to leave – in Taxi Panahi considers the same reality with more serenity, even humor, though his protest results no less trenchant. His third film since receiving the ban in 2010, Taxi is a perfect complement to its predecessors, adding another chapter to Panahi’s exceptional and thoroughly stirring exercise in meta-filmmaking.

For all three films, Panahi circumvented the ban by employing guerrilla filmmaking tactics. This time around, he installed a camera inside a taxi and filmed himself driving around Tehran, holding conversations with various passengers. The style is immediately reminiscent of Ten by Panahi’s erstwhile mentor and frequent collaborator, Abbas Kiarostami. However, Taxi isn’t interested in the same probing of reality vs. fiction as Kiarostami’s film. The artifice is purposely dispelled early on when the third passenger, a peddler of pirated DVDs, recognises Panahi and exposes the first two passengers as actors for having referenced dialogue from the director’s 2003 film, Crimson Gold. Moreover, unlike Ten, which only featured stationary dashboard cameras, Taxi employs several video devices, including an iPhone and a compact digital camera, and the entire film takes place in simulated real time, forsaking all plausibility of documentary veracity.

The passengers’ allegorical function is thus established and the film assembles a portrait of contemporary Tehran that offers a reflection on the injustice suffered by its inhabitants, eventually concentrating on the Iranian government’s draconian restrictions on filmmaking. The macro-dimension is introduced by the first few passengers, whose conversations touch on subjects such as Iran’s notorious capital punishment practices and the laws hindering women from receiving rightful inheritance. The film narrows its thematic focus once Panahi picks up his real-life niece, a truly remarkable actress.

Sharp-witted and delightfully cheeky, the young girl questions all impositions of authority. She aspires to be a filmmaker and films everything on her compact camera, intending to compile a documentary that truthfully depicts her life. However, she cannot understand her teacher’s guidelines for producing a distributable film (i.e. the same rules the Iranian government imposes on all film productions). The prohibition of “sordid realism” proves particularly perplexing. How can realism be sordid, she asks her uncle. Isn’t this a contradiction? Panahi, of course, can only agree with her. The guidelines also disallow all discussions of economic or political matters, depictions of violence and suffering, and dictate that good guys are not allowed to have Iranian names — only Islamic ones — or to wear a tie. In Taxi, Panahi deliberately contravenes every one of these guidelines.

Throughout, Panahi gets excellent comic mileage out of highlighting the absurdity of the government’s impositions, generating great sympathy towards its characters and edging the film into satirical territory. Despite the laughs, Taxi never loses touch with the desperate reality at the heart of its formal experiment and moments such as an exchange with a lawyer fighting battles similar to Panahi’s keep bringing it back into stark perspective. Finally, the solemn and quietly devastating conclusion refuses to end the film on an unwarranted note of optimism.

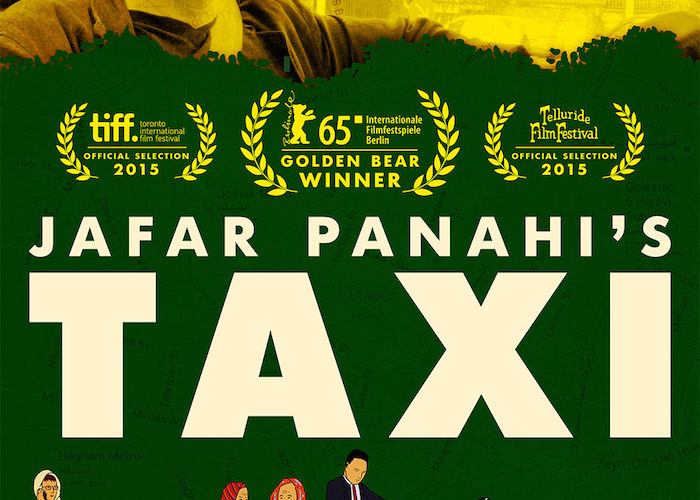

Taxi premiered at Berlinale and opens on October 2nd.